Now Reading: Sounding the alarm: ESA introduces space environment ‘health index’

-

01

Sounding the alarm: ESA introduces space environment ‘health index’

Sounding the alarm: ESA introduces space environment ‘health index’

22/10/2025

1360 views

16 likes

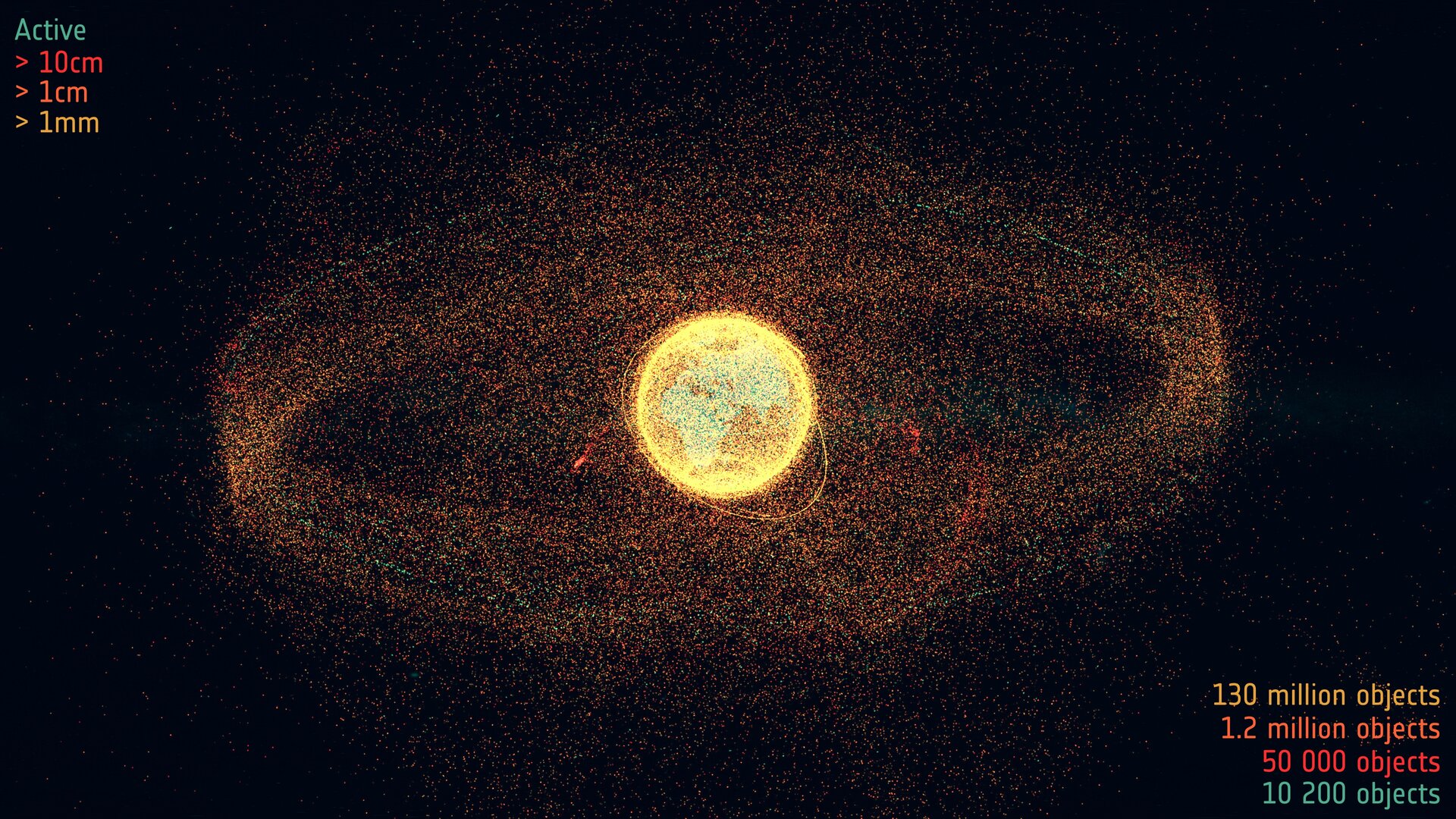

The congestion and pollution of Earth orbit is quickly getting worse. We need to be able to quantify how our behaviour impacts the orbital environment in the future. To this end, the European Space Agency (ESA) is adding a new health index to its yearly Space Environment Report that summarises in one number the status of our space environment over time.

“The space environment health index is an elegant approach to link the global consequences of space debris mitigation practices to a quantifiable impact on the space debris environment,” says Stijn Lemmens, space debris mitigation analyst at ESA.

“With the new metric, ESA is promoting a common language for assessing the impact of our space activities and making consequences concrete.”

The need for a yardstick

To keep our space environment safe and sustainable, we need a way to measure its overall health and quantify the impact each new mission will have.

Just as climate scientists use temperature as a key indicator of global warming, the space community needs a clear, quantifiable metric to assess the impact of objects and missions on orbital sustainability.

The Space Environment Health Index provides such a metric. It is a single score that reflects how healthy or stressed the orbital environment is and what the consequences will be in a 200-year time period.

Even if one number can never explain all the intricacies involved, it will provide a useful impression of the space environment’s health that speeds up high-level conversations. Also, it will provide a framework to evaluate individual missions on how they will impact the overall state.

The Health Index supports global sustainability efforts, including ESA’s own Zero Debris approach, which aims to eliminate debris generation from ESA missions by 2030.

Ingredients of the new metric

For nearly 10 years, ESA and European academia have been working on understanding the links between space traffic, operator behaviour and orbital dynamics as a combined system. The Space Environment Health Index is designed to distil complex factors into one understandable score.

Each object or new mission has certain qualities that can be converted into a positive or a negative effect on the Index, such as:

- Size: How big is it and what shape does it have?

- Lifetime in orbit: How soon will the object naturally re-enter or be removed?

- Collision avoidance capability: Can the object manoeuvre to prevent collisions?

- Passivation measures: Has the object been made safe from explosions after its mission ends?

- Fragmentation risk: What is the likelihood of the object breaking apart and creating debris?

By combining these elements, it captures the risks of a mission’s potential to create space debris, how that debris will increase collision risk for one’s neighbours, and how it will statistically have impacted the space environment after 200 years (see the full ESA Space Environment Report for calculation details).

A high score indicates a greater negative impact on the environment, while a low score reflects more sustainable behaviour. It can then work like an energy-efficiency rating for appliances: in the future, a mission could be rated “A” for sustainability, giving operators and regulators a clear benchmark.

All objects’ scores together result in a global Health Index that indicates the overall state of the orbital environment compared to a reference baseline.

Our current score: the alarm is sounding

The Space Environment Health Index measures how sustainable Earth’s orbital environment is. A value of 1 represents the proposed threshold for long-term sustainability. Anything higher means that the space environment becomes less then desirable for operations over time and could eventually become unstable.

This benchmark of the Health Index is based on the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) guidelines as in 2014, before the boom in large constellations. These guidelines outlined what a ‘healthy’ space environment should have looked like in 200 years, assuming space operators follow space debris mitigation rules as established then.

Even back in 2014, the forecast was not ideal. The expected future was already three times riskier than the minimum deemed desirable. Today, with more satellites and more debris, the risk has climbed to four times higher. Despite many satellite operators already adopting space debris mitigation practices, more action is needed.

We are now at Health Index level 4, far beyond the sustainability threshold. Stronger action is required to protect our future in space.

Potential uses of the Health Index

The index is more than a scientific tool – it is a practical decision-making aid. It can be applied to mission design to minimise its environmental impact, similar to other life cycle assessment tools and practices. A low score becomes a design target, encouraging choices like shorter orbital lifetimes, reliable deorbiting systems and strong collision avoidance capabilities.

“Even if the definition of the Health Index may seem very theoretical, at ESA we have already successfully applied this concept in practice,” explains Francesca Letizia, space debris mitigation engineer at ESA.

“We had to evaluate different policy options to define the Zero Debris approach. We used the Health Index model to translate the mandate for a Zero Debris approach into numbers, identifying a path that would not exceed the orbital sustainability threshold.”

Another promising area is licensing, regulation and insurance. Authorities could adopt the index as part of licensing criteria, ensuring new missions meet sustainability thresholds and pass certain risk assessments. Over time, the index could feed into updated mitigation guidelines, ecodesign pipelines for space systems and become a part of policies in space.

Why act now?

Some might ask: if the real trouble is projected in 200 years, isn’t that enough time to solve it later? The reality is that the problem is urgent. Every new object now adds to the cumulative risk over time. Fragmentation events today will have consequences for decades, and the era of large constellations has accelerated the challenge.

Long before the space environment becomes truly unusable, the cost of operating in space will skyrocket. Certain orbits may become inaccessible, also impacting human spaceflight with its stringent safety standards.

The Space Environment Health Index helps us act now by making sustainability measurable. It shows how ambitious efforts, such as ESA’s Zero Debris-by-2030 promise, are essential to have a chance at continued access to space. It provides an option for transparency, accountability and a shared framework for collaboration, driving responsible behaviour across the space sector.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

04Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

04Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

05Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

05Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits