Now Reading: Space Force wants competition. Satellite makers want stability.

-

01

Space Force wants competition. Satellite makers want stability.

Space Force wants competition. Satellite makers want stability.

The Pentagon says it wants Silicon Valley speed with defense-grade reliability. It also wants lower costs and more competition. What it’s learning is that you can’t just flip a procurement model on its head without rattling the industrial base you spent decades shaping.

That tension is playing out most clearly in space.

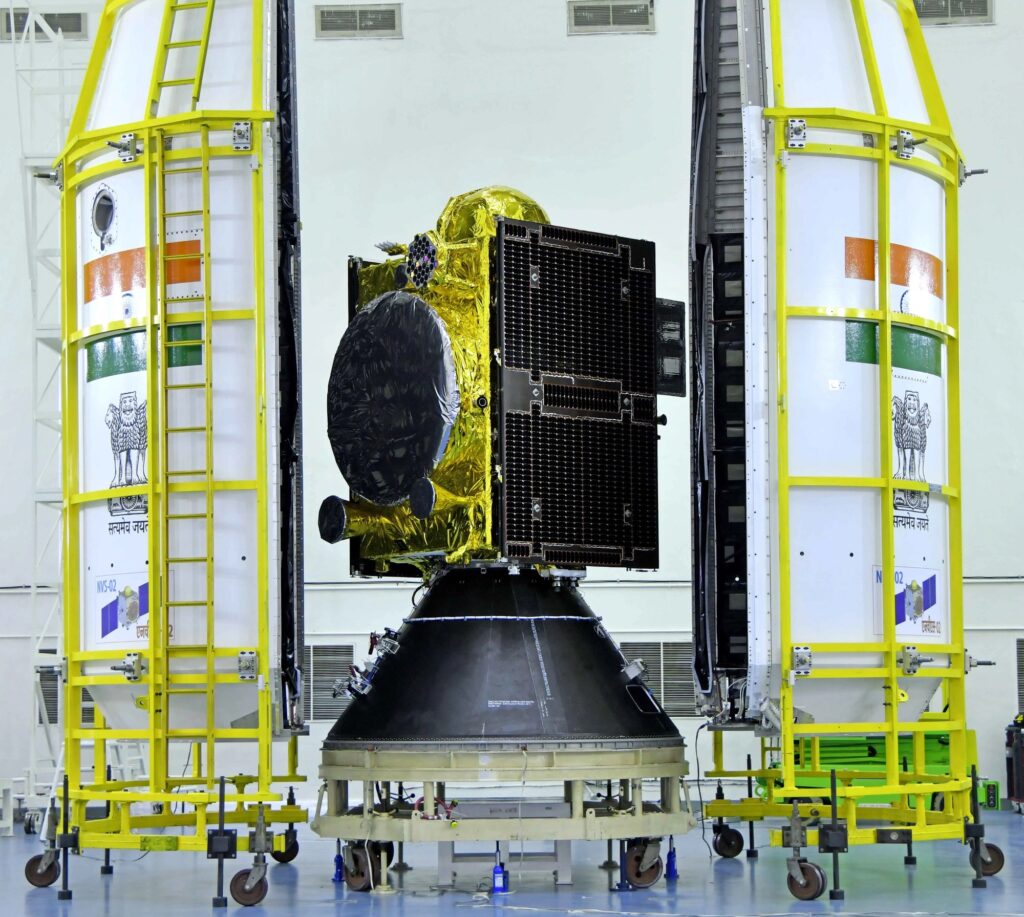

When the Space Development Agency was created in 2019, it was designed to solve a problem the Pentagon had been wrestling with for years: how to build space systems that could survive and function in a conflict with a peer adversary. U.S. military satellites had become increasingly vulnerable because they were few in number and expensive.

SDA’s answer was the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture, a network of hundreds of satellites in low Earth orbit designed to provide data transport, missile warning and tracking. To procure these satellites, the agency holds competitive down-selects, forcing companies to put skin in the game. Vendors are asked to deliver hardware on timelines more common in the commercial sector while they bid on contracts in two-year cycles. Officials say the approach taps commercial investment and gives companies regular shots at winning work.

It’s hard to argue with that logic. That setup has opened the door to commercial players like York Space and Rocket Lab to share constellations with traditional defense players such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, L3Harris and Boeing. The Space Force is now looking to adopt that model for other satellite procurements.

But here’s what doesn’t fit neatly on a slide deck: Factories don’t like uncertainty. Neither do investors.

Behind the rhetoric about competition and innovation, not everyone is convinced SDA’s approach is a win-win, as companies have to keep production lines warm and preserve specialized labor even when they didn’t win the most recent tranche and won’t get another shot until the next cycle.

Kay Sears, vice president of space, intelligence and weapon systems at Boeing questioned at a recent industry forum how companies should keep their people employed and production facilities running amidst inconsistent awards. “That’s going to be a problem,” Sears said.

Large defense firms can deal with that, but “new entrants have to return money to their investors.”

Sears insisted she was not being critical of SDA’s model, just pointing out the financial realities.

From the government’s perspective, the benefits are real. Having multiple companies in competition, Maj. Gen. Stephen Purdy said, gives the government options, so if one contractor stumbles or underperforms, the mission doesn’t grind to a halt.

In response to Sears’ concerns, Purdy said he agreed that companies have to generate a return to investors, ideally by selling to commercial customers alongside the government so they’re not dependent on defense contracts to survive.

There’s just one problem: Not every military satellite technology has a ready-made commercial market waiting to absorb excess capacity.

The head of the Golden Dome missile defense program, Gen. Michael Guetlein, recently gave a blunt assessment of how the Pentagon arrived here. Speaking at the Reagan National Defense Forum, he said DoD helped create its own industrial base challenges by driving consolidation in the sector, largely because it spent decades buying small numbers of expensive, bespoke systems.

That approach, he argued, left industry optimized for low-rate, high-cost production rather than the scale now required for efforts like Golden Dome, which depend on large numbers of satellites and interceptors. Guetlein said the department is now trying to reshape an industrial base that it effectively trained to do the opposite.

A slate of procurement reforms the Pentagon recently rolled out, Guetlein said, are “about how to change that demand signal and how to make it consistent across several years, not just one year at a time.”

That last line may be the quiet crux of the whole debate. The Pentagon wants faster, cheaper, more resilient systems. Industry wants predictable demand and a return on capital. SDA is trying to bridge that gap. Whether that model produces a healthier industrial base may depend less on how innovative the contracts look and more on whether the demand signal stays steady long enough for companies to build something durable underneath it.

This article first appeared in the January 2026 issue of SpaceNews Magazine.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly