Now Reading: Space Force’s X-37B space plane is testing ‘Zylon’ material to help crew and cargo land on Mars

-

01

Space Force’s X-37B space plane is testing ‘Zylon’ material to help crew and cargo land on Mars

Space Force’s X-37B space plane is testing ‘Zylon’ material to help crew and cargo land on Mars

The U.S. Space Force’s X-37B space plane is carrying a sample of material that could some day help NASA land cargo and crew on Mars.

The X-37B launched on its eighth mission on Aug. 21 atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Aboard the space plane were a number of experiments, including a laser communications system and the “highest-performing quantum inertial sensor ever tested in space,” according to the U.S. Space Force. The sensor is a much more precise and resilient alternative to GPS that could allow spacecraft to determine their position even in GPS-denied environments.

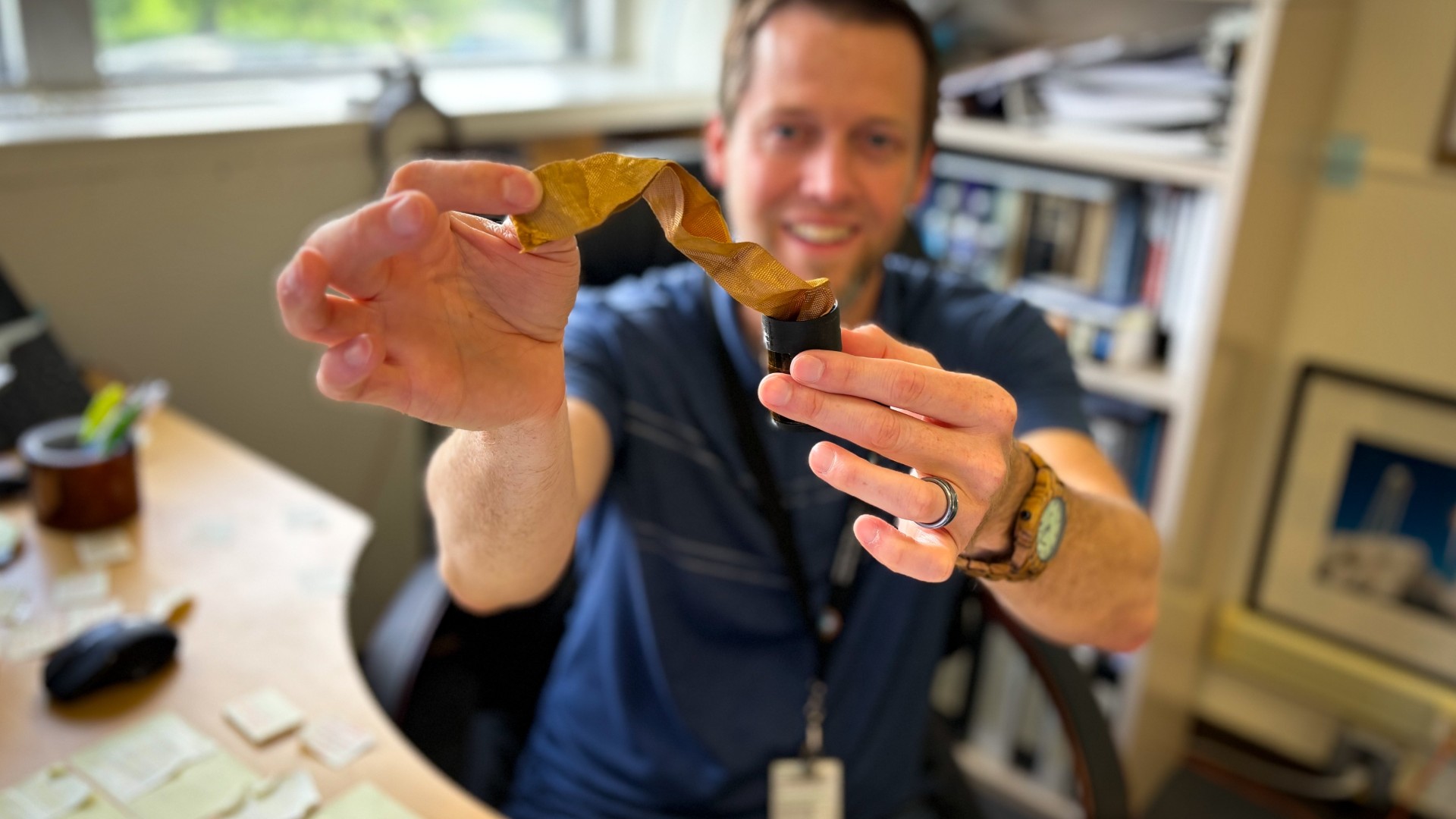

But while these two emerging technologies got most of the attention, the X-37B was carrying another potentially revolutionary experiment. Aboard the secretive space plane was a strip of webbing known as Zylon, a strong synthetic polymer developed by SRI International. Zylon webbing is being eyed to construct straps for NASA’s Hypersonic Inflatable Aerodynamic Decelerator (HIAD), a flying-saucer aeroshell that could someday be used to land crew and cargo on Mars.

With NASA’s current push for a greater emphasis on exploration of the moon and Mars, technologies like HIAD could become vital to the agency’s plans — as could the need for materials to ensure they work as designed.

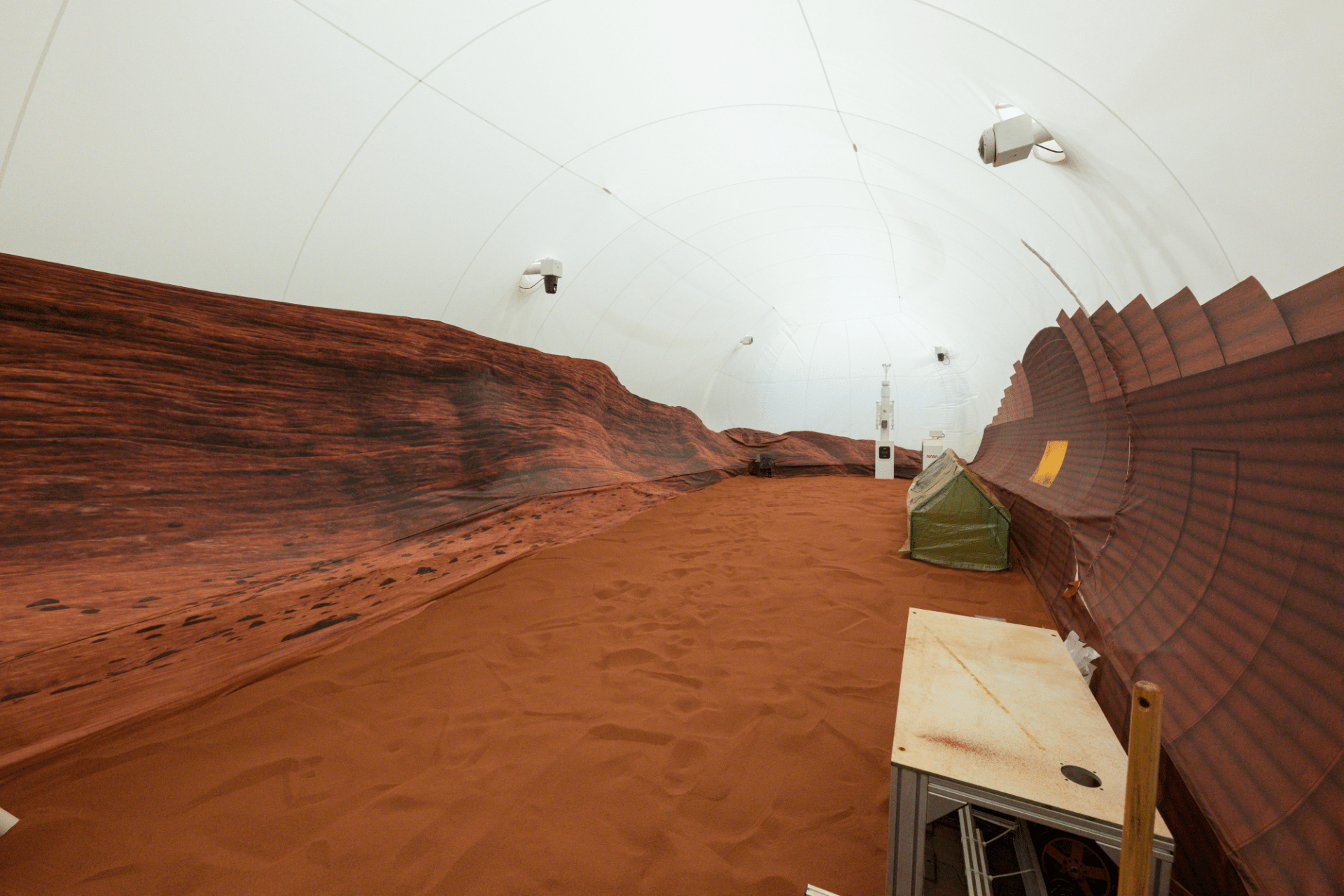

“We’re researching how HIAD technology could help get humans to Mars. We want to look at the effects of long-term exposure to space — as if the Zylon material is going for a potential six- to nine-month mission to Mars,” said Robert Mosher, HIAD materials and processing lead at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia, in an agency statement. “We want to make sure we know how to protect those structural materials in the long term.”

Aeroshells like HIAD could someday help large spacecraft, rovers or other equipment descend through the atmospheres of planets or moons like Saturn’s giant satellite Titan, according to NASA. That’s were materials like Zylon come in.

Zylon is being eyed for use in the straps that hold the HIAD shell together and distribute loads evenly throughout its structure. But scientists will need to know how the material reacts to the harsh environment of long-term spaceflight before NASA sends it on the journey to Mars or beyond.

To that end, the X-37B is carrying multiple samples of Zylon in canisters, some of which are embedded with temperature and humidity sensors. The samples were packed using two different techniques: one in which the material is tightly coiled, and another in which it was “stuffed in,” NASA wrote in the statement describing the experiment.

“Typically, we pack a HIAD aeroshell kind of like you pack a parachute, so they’re compressed,” Mosher said. “We wanted to see if there was a difference between tightly coiled material and stuff-packed material like you would normally see on a HIAD.”

The X-37B is a reusable space plane that allows scientists the opportunity to send materials and other experiments to space and then study them upon their return to Earth. Mosher and other NASA scientists will study the samples of space-flown Zylon alongside samples that remained here on Earth, analyzing how the material may have degraded or otherwise changed in the environment of outer space.

“Getting this chance to have the Zylon material exposed to space for an extended period of time will begin to give us some data on the long-term packing of a HIAD,” Mosher said in the statement.

NASA has already tested a HIAD prototype. On Nov. 10, 2022, a ULA Atlas V rocket launched from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California carrying a HIAD technology demonstrator called Low-Earth Orbit Flight Test of an Inflatable Decelerator, or LOFTID.

After LOFTID deployed from its Centaur upper stage ride, it inflated at around 78 miles (125 km) up and successfully reentered Earth’s atmosphere, landing in the Pacific Ocean around 500 miles (800 km) from Hawaii.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly