Now Reading: Space is a warfighting domain. We need wartime urgency for procurement reform.

-

01

Space is a warfighting domain. We need wartime urgency for procurement reform.

Space is a warfighting domain. We need wartime urgency for procurement reform.

When America embarked on the journey to build the Arsenal of Democracy in World War II, President Roosevelt had a simple instruction: “speed, speed, speed.” His emphasis on speed spurred on the production of lethal, mass-producible American warplanes that enabled the United States to win WWII.

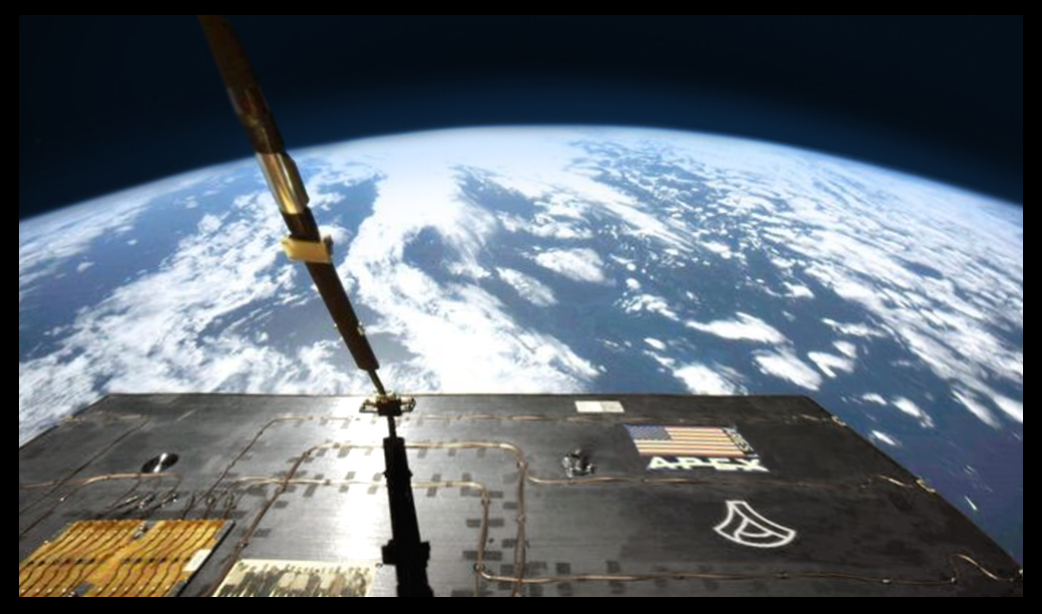

Some 80 years later, the urgency for speed is just as relevant in another domain: space.

It’s no exaggeration that we are in the midst of a second space race, this time with our great power rival: China. Over the past decade, China has made stunning strides in its development of military space capabilities.

Numbers clearly demonstrate this assertion. China’s orbital presence grew from 36 satellites in 2010 to more than 1,000 in 2024, along with a growing suite of counterspace weaponry. A May Defense Intelligence Agency report found that China will field 4,000 hypersonic glide vehicles and 60 Fractional Orbital Bombardment Systems by 2035. In June, Gen. Stephen Whiting of U.S. Space Command assessed that Chinese space technologies matured “breathtakingly fast,” while others assert that Beijing has developed a “kill mesh” of sensing and shooting capabilities which threaten American satellites. And just this month, China unveiled new space-going hypersonic missiles at a massive military parade.

The takeaway is obvious: Despite its peaceful rhetoric, China is readying a fleet of space weapons in preparation for conflict. As this threat accelerates, our response must exceed that pace. The Space Force and Department of War cannot counter this challenge with business-as-usual procurement. Roosevelt’s mandate for “speed, speed, speed” must become our guiding principle once again. This demands immediate, transformative reform in how we acquire space capabilities. The Pentagon should partner aggressively with commercial innovators to streamline proposal processes, shift away from sluggish cost-plus contracts toward fixed-price and performance-based models and implement more flexible data rights policies that incentivize rapid innovation.

America won the first space race through urgency and industrial might; winning this second contest requires nothing less than a complete reimagining of how we build and deploy space power.

Gen. Saltzman’s call to action for the USSF

The Space Force has long recognized China’s growing aggression in space and has acknowledged the need for the service to adapt to meet the moment. Gen. Saltzman’s release of the Space Warfighting Framework in March highlights the Space Force’s vision and plan to transform into a warfighting service focused on maintaining space superiority. Saltzman captured the urgency in the foreword: “In the face of growing threats in, from, and to space, access to the [space] domain can no longer be taken for granted.”

Not long ago, politicians called for cooperation with great power rivals in the space domain. Now, it’s a common adage that the first shots of the next war will be fired in space. This paradigm shift demands an equally dramatic transformation in how we equip our guardians. Traditional procurement processes — designed for a different era — cannot deliver the capabilities needed for this new reality. More efficient, more effective and expedited procurement is not merely desirable; it forms the foundation of credible deterrence in space. The most advanced space defense technologies, electronic warfare systems, and rendezvous and proximity operations are meaningless if procurement delays prevent their timely employment.

We now need to quickly instantiate and solidify the infrastructure and organization to build out American military space power at scale to deter our adversaries. The way that we procure must transform to ensure we have American superiority in space.

Technological innovation is outpacing procurement innovation

We have arrived at this precipice in part because of massive strides in space technology. Space launch costs 20 times less than it did during the Space Shuttle era. Advancements in artificial intelligence and computing power allow satellites to perform tasks and conduct maneuvers that are orders of magnitude more complex than their historical analogues. The space industry has never been more accessible or diverse in its suppliers.

Alarmingly, though, the way the Pentagon acquires technology has not evolved as effectively as the technology itself. The Space Force made strides the last decade transitioning from small numbers of prototypes to scaling production, but delivery at scale has been too slow. Worse yet, little interest exists as it pertains to rapidly accelerating production of operational capabilities.

This needs to change, quickly. The Space Force must transition from fielding small numbers of experimental systems to deploying robust constellations of operational assets that can effectively deter adversaries and deliver decisive effects when required. Procurement challenges are deep and structural across DoD: a 2025 GAO study noted that the average timeline for a major Pentagon program to deliver even an initial capability is now over 12 years.

The Space Force does not have the luxury of a decades-long timeline to better institutionalize spacepower given the rising threat from China. There is increasing consensus in Washington that the U.S. is reaching a “window of maximum danger” in our military balance with China, which could incur risk of an invasion of Taiwan as soon as 2027. Part of the reason why my company, Anduril Industries, has built a space business in the last two years is because our leadership realized that securing the space domain is a necessary precondition to establishing deterrence terrestrially.

Getting our procurement process right — quickly — is an imperative we cannot afford to undervalue any longer.

Three principles for procurement reform

As the smallest and nimblest service, the Space Force can both act faster than other military branches and serve as an example for the rest of DoD for how to similarly modernize. There are three key principles that should animate these reforms and ensure American space dominance.

First, the government should adhere to the adage of “show, don’t tell.” The Space Force cannot continue to bet hundreds of millions of dollars or even billions of dollars upfront on one company based on a compelling written proposal. Onerous Request for Proposals advantage companies that write well but may not bring forward those who build and deploy the best technology. No one shows up to a car dealership and asks them to submit a 300-page proposal on the performance of the car — a test drive is proof of its suitability. We must move to the same model in defense procurement.

The status quo allows companies to game the system and write strong proposals without any ability to actually deliver on what they claim. This model delivers suboptimal results for both the Space Force and the American taxpayer. Fundamentally though, the system incentivizes these bad results. And now that we live in a world of generative AI that can write near-perfect proposals, the risk of rewarding a contract to a company that can’t perform only increases.

The only way to ensure a different outcome is to pursue a different process. This means putting competition at the core of procurement. The government should use prototypes, pitches, demos and competitions to force industry to demonstrate that it can deliver. Moving toward a “show, don’t tell” contracting approach will weed out companies that can’t perform and ensure contracts go to the best companies.

Second, cost-plus, fixed fee contracts are stifling innovation. Cost-plus contracts gained traction during the first and second World Wars, when the government offered to reimburse contractors for costs plus a defined profit margin during the “all hands on deck” production mentality. Over time, these contracts became the standard for high-risk, innovative defense development programs where requirements and costs were difficult to predict. Unfortunately, the modern cost-plus contract reduces incentives for cost control, efficiency and rapid development.

The emergence of defense companies like Anduril demonstrates a compelling alternative: using fixed-price contracts to deliver innovative military capabilities in the space domain with greater speed and efficiency. These newer entrants have proven that even technically challenging systems can be developed under fixed-price models when paired with modern development practices and an appetite for responsible risk taking — ultimately, delivering capabilities to warfighters faster while maintaining cost discipline.

In addition to Fixed Price contracts, Other Transaction Agreements/Authority (OTA), provide essential flexibility on a comparatively compressed timeline to traditional contracting. Ironically, OTAs are a Space Race-era concept proffered by President Eisenhower to accelerate research and development in space following Sputnik.

Given the Space Force’s reduction in its civilian workforce, OTAs present a valuable opportunity to streamline acquisition while reducing the administrative burden of Federal Acquisition Regulation-based contracts. Companies developing superior space domain capabilities for the United States should be rewarded commensurately for innovation and risk-taking. The combination of OTAs and firm fixed price (FFP) contracts creates a framework where industry partners receive appropriate financial incentives when they successfully deliver capabilities, ultimately encouraging the private sector to make bold investments in advanced space technologies that enhance national security.

A similar risk-taking mentality is why Amazon — once only a bookseller — launched AWS, or why SpaceX took on massive risk to build Falcon 9. The commercial industry rewards performance on big bets and subsidizes successful risk-taking. But with cost plus contracting, all of the upside is truncated. That model won’t work as we seek to harness the cutting-edge capabilities of leading technology companies to ensure U.S. superiority in space. We need to move to FFP contracts and OTAs which offer significantly more flexibility and upside for the big bets that we need in space.

That said, the space sector has struggled with FFP contracts in the past. With FFP contracts, companies assume the risk for cost overruns, and thus are inherently incentivized to optimize for efficiency so they can maximize profit. Some companies have bid a low price in order to win the FFP contract, and then subsequently suffered massive cost overruns and scheduling delays, leading the Space Force to cancel or restructure several large scale programs. As such, the shift toward FFP contracts is reliant on the “show don’t tell” approach previously noted. Companies that bid on FFP contracts must demonstrate that they can deliver on the capabilities, schedule, and price that they propose, which is easier for the government to identify and monitor through demos and competitions.

Third, the government must radically rethink its approach to data rights. The Department of War, understandably, is very concerned about data rights. In some cases, it wants to control intellectual property as a way to avoid vendor lock.

Vendor lock has many meanings, but its relevance for space purposes relates primarily to the value that a given software or hardware item is adding to the desired capability. Typically, this is not an underlying codebase, but instead interfaces and applications themselves. If these tools are standardized, then any of the black boxes can be easily competed and replaced, whether for price reasons or underperformance. A focus on a modular open systems approach, or MOSA, can mitigate vendor lock concerns more effectively than traditional data rights.

MOSA is also aligned with how the commercial industry operates. This is how Qualcomm and AT&T work together, as well as the same way that Microsoft and NVIDIA collaborate on AI and cloud computing. Simply put, the structure of their collaboration is to have some set of standards that everyone agrees to build to with cohesive but severable modules. The MOSA approach is a pathway to mutually agreeable and speedy work on vital programs.

It is worth noting that traditional data rights approaches almost always fail to solve vendor lock concerns. The reality of both technical data and software is that new engineers find it very hard or impossible to maintain or improve complex code or designs made by someone else. Further, though the government may get broad data rights to software or hardware, it rarely actually shares that intellectual property across departments or programs. A focus on interoperability is the elegant and more effective solution because it provides an approach that solves the problem in application, not just in theory.

Accelerate what the Space Force already does

It turns out that President Roosevelt’s advice — “speed, speed, speed” — is as applicable to our arsenal of satellites and missiles as it is to B-24 bombers and Sherman tanks. Importantly, the Space Force is already at work on efforts that adhere to the above three principles.

For example, the emerging Space Based Interceptor program architecture requires industry to self-fund development, at which point the government will make performance-based awards through a prize competition. Space Systems Command is emerging with other innovative acquisition models. The emerging mentality in the Space Force is best summed up by Major General Stephen Purdy, who said earlier this year that his priorities remain fixed on program management discipline and aggressive reform. Accountability, in space acquisition, Purdy said, is a “two-way street.”

Efforts to disrupt the status quo and secure the foundations of American spacepower are also a two-way street. They cannot solely be the responsibility of the industrial base, nor can they be just the Space Force’s job. But together, industry and the military can accelerate efforts at reform so that if space does indeed remain a warfighting domain, it is not the U.S. that is at a disadvantage.

Gokul Subramanian is Senior Vice President of Engineering at Anduril Industries.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine.The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly