Now Reading: Space telescopes at light speed

-

01

Space telescopes at light speed

Space telescopes at light speed

Light is the fastest phenomenon in the universe, clocking in at just under 300,000 kilometers per second. The telescopes that observe that light, from radio waves to gamma rays, are built at rather slower speeds.

Take, as one example, the James Webb Space Telescope. NASA began feasibility studies for the mission in the mid-1990s and selected contractors to design and build it in 2002. However, JWST did not launch until the end of 2021, after major cost and schedule overruns.

Now, NASA wants to accelerate that pace. The agency wants to prove it can build and launch major astrophysics missions faster and more predictably. From bringing the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope to the launch pad months ahead of schedule to reimagining smaller missions, NASA is rethinking how it develops space observatories.

And it’s doing so while a team building a privately funded space telescope aims to outpace the government and move faster still.

‘Don’t tell me we can’t go fast’

NASA’s first step in speeding up development of missions is avoiding delays with its next major astrophysics mission, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. So far, it’s succeeding.

During a session at an American Astronomical Society (AAS) conference in Phoenix Jan. 5, project officials said Roman — a space telescope with a mirror the size of Hubble but a much wider field of view — was on track for a launch as soon as September, months ahead of its formal launch commitment date of May 2027.

Julie McEnery, senior project scientist for Roman at the Goddard Space Flight Center, even gave a specific launch date and time: Sept. 28 at 6:40 a.m. Eastern. “It’s really real,” she said. “We’re at the finish line here.”

NASA completed assembly of the spacecraft in November, which is now undergoing testing at Goddard. It is scheduled to ship to the Kennedy Space Center in June to prepare for its launch on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy.

“We have not made compromises. This mission meets or exceeds all science requirements,” McEnery said. “The mission that we described at the mission confirmation review is the one that we built.”

For the last few years, NASA has emphasized the importance of keeping Roman within its cost and schedule commitments to demonstrate it had learned the lessons of JWST and win support for future large space telescopes, like the proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory. Besides running ahead of schedule, Roman has also remained within its budget, with a total lifecycle cost of $4.3 billion.

While Roman is still several months from launch, agency officials are ready to take a victory lap. “I don’t want to hear that we can’t do flagships on time and on schedule. The Roman team has proven we can,” said Shawn Domagal-Goldman, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, at an agency town hall the same day at the AAS conference.

Roman was just one example he gave about how he wanted to accelerate development of astrophysics missions. Another is an effort to reboost Swift, a gamma-ray telescope launched in 2004 and whose orbit is decaying from atmospheric drag. NASA said last year that the spacecraft was in danger of reentering as soon as late 2026 without action.

Last fall, NASA awarded a $30 million contract to satellite-servicing startup Katalyst Space to develop a spacecraft — a repurposed tech demo mission the company was already building — to dock with Swift and raise its orbit. That mission is scheduled to launch as soon as this June on a Pegasus XL.

If the reboost mission sticks to that schedule, “we’ll have gone from the board room to the launch pad in about 12 months,” Domagal-Goldman said. That pace, motivated by the urgency to reach Swift before it reenters, is far greater than even cubesat-class astrophysics missions that can take several years to develop.

There is, he acknowledged, a risk the mission won’t work: A reboost like this has not been attempted before, and this will be Katalyst Space’s first mission. The chance of that, he argued, was balanced by the benefits of keeping Swift in service for years to come.

“Don’t tell me we can’t go fast. Don’t tell me we can’t identify the places where it’s appropriate to take risk,” he said. “There’s a decent chance this is not going to work, and it’s still the right thing to do.”

The emphasis on speed extends to future missions. NASA is revising an announcement of opportunity (AO), a call for proposals, that it delayed last year for a Small Explorer astrophysics mission. NASA is tightening the review process, skipping a round of feasibility studies, to allow the selected mission to launch on its original schedule despite delaying the release of the AO by a year.

Domagal-Goldman said he is interested in other ways to speed up the AO process for future missions, with a forum planned later this year to solicit ideas. A separate “innovation workshop” in the spring will explore how emerging capabilities in the commercial space sector, such as new large launch vehicles, can help mission development.

“We’re trying to find ways to go fast,” he said.

Accelerating habitable worlds

The flagship telescope that will follow Roman, the Habitable World Observatory (HWO), will offer a worthy test.

NASA has started early planning work on the mission, which is expected to launch no sooner than the early 2040s.

Immediately after the NASA town hall at the AAS conference, the agency announced it selected seven companies to perform relatively low-cost studies on various technologies that could be incorporated in the mission, such as the telescope’s mirror, thrusters and ability to be serviced.

The studies are part of broader efforts by NASA to mature the design and critical systems needed for the observatory before starting development: one of the lessons learned from JWST. NASA did not release a total contract value but these are relatively small studies on the order of a few million dollars total.

“We need to take a lot of time up front to not just understand the scope of this project but also understanding the architectures that deliver the science,” Domagal-Goldman said at a conference session Jan. 6.

That would allow the mission to go quicker later, he argued. “The things you do to move faster on the larger-scale missions at the outset are things we’re asking this community, and the people you work with outside this room, to do over the next few years,” he said.

NASA has not announced any changes to the development schedule for the mission, which calls for it to be ready to go into development in the early 2030s and for launch as soon as the early 2040s. However, it fits into a broader push by NASA to accelerate development of astrophysics missions — a push coming from the very top.

“I love the flagship missions that we have in the science portfolio. I just want to see more of them,” NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman said at an agency town hall Dec. 19, the day after he was sworn in. “It would be great if we were launching flagship missions with even a greater cadence.”

A billionaire’s bet on a space telescope

One of the most popular sessions at AAS was a side meeting Jan. 7 with a rather anodyne name. The first clue that the session would be unusual was an open bar in the hallway outside the meeting room, a rarity at a conference where anything more than coffee is considered a luxury.

However, the astronomers attending were not merely interested in a mid-afternoon cocktail. A crowd packed the room and overflowed into the hallway to hear about one of the most ambitious efforts yet to develop private observatories. The session? “The Schmidt Observatory System — More Astrophysics for More People.”

Schmidt Sciences, founded by former Google chief executive Eric Schmidt and his wife Wendy, used the session to unveil the Schmidt Observatory System, a set of three ground-based optical and radio observatories and one space telescope the organization is paying to develop.

“Throughout the history of astrophysics, discovery has happened in leaps and bounds that coincided with technological improvements,” said Arpita Roy, head of the astrophysics and space science institute at Schmidt Sciences. “We think these observatories not only answer existing questions but open up new discovery space.”

Philanthropic funding of ground-based observatories goes back centuries, and many major telescopes in operation today have relied partially or entirely on private funding. But previous efforts at privately funded large space telescopes have floundered.

More than a decade ago, the B612 Foundation proposed Sentinel, a space telescope to look for near Earth objects. The organization struggled to raise funding, though, and dropped Sentinel after NASA started a similar mission, NEO Surveyor.

Around the same time, another private group, the BoldlyGo Institute, sought to raise money for private space missions, but made little progress.

The difference here is that the Schmidt Observatory System is backed by a billionaire who has committed money for all four observatories. “What we’re discussing here is a very large, purely charitable gift from Eric and Wendy Schmidt,” said Stu Feldman, president of Schmidt Sciences.

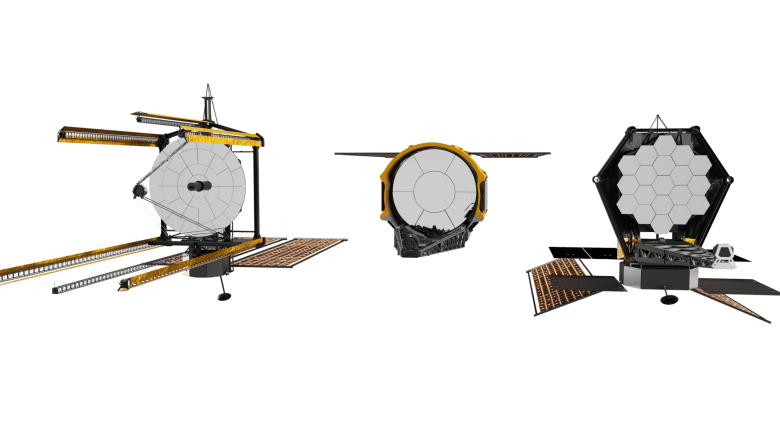

Confirming rumors that have been floating in the astronomy community for years, Feldman said his organization first designed a very large space telescope with a mirror 6.5 meters across: the same diameter as the James Webb Space Telescope, but in a single piece rather than in segments. The organization went so far as to acquire a mirror blank, the glass from which the mirror would be ground, of that size.

The problem was that aspects of the design proved infeasible, notably the ability to get it into its desired orbit in the near future. “Starship schedules are malleable,” he said. “We simply said it’s not going to work.”

Instead, in the fall of 2024 Schmidt Sciences pivoted to a smaller telescope that could be launched by medium-class rockets. By November 2025, the organization was ready to proceed with such a space telescope, called Lazuli.

Changing schedule and cost curves

While smaller than the original design, Lazuli remains an impressive observatory. It will have a mirror three meters across, larger than the 2.4-meter mirrors on Hubble and Roman. It will carry a wide-field camera, a spectrometer and a coronagraph, an instrument that blocks light from a star to see any planets orbiting it.

“Lazuli is going to deliver Hubble-class image quality,” said Pete Klupar, executive director of the Lazuli project at Schmidt Sciences and former director of engineering at NASA’s Ames Research Center. He added that the project would take three years and cost in the range of hundreds of millions of dollars — an order of magnitude below previous flagship astrophysics missions.

Achieving those goals involves using commercially available components. He estimated that 80% of Lazuli will use off-the-shelf hardware with flight heritage. The remaining 20% primarily involves some elements of the telescope itself and its instruments.

Klupar said the organization has found ways to streamline development to enable launch as soon as mid-2028. That includes doing spacecraft assembly near the launch site in Florida and potentially skipping some environmental tests, like acoustics and vibration.

“We convinced ourselves that there may be a path to eliminate some of those system-level tests,” he said, based on earlier work on the larger design.

Another factor helping to speed development of the spacecraft is the management structure. “We have one shareholder,” he said, a reference to Eric and Wendy Schmidt.

“This eliminates analysis paralysis and allows us to take credible, calculated risks that others just can’t do.”

While the astronomers who crowded into the room were intrigued by Lazuli, there was also an undercurrent of skepticism. They privately doubted the ability of any organization to build a Hubble-class space telescope on the schedule and budget of commercial geostationary communications satellites that are produced on assembly lines.

“A lot of people don’t believe we can do it,” Klupar acknowledged. “We’re on an aggressive but achievable path.”

“I will be utterly shocked if everything is on time,” admitted Feldman. He was confident, though, that Lazuli can achieve one of its goals, “to change the schedule and cost curve of astronomy.”

“Speed is its own form of intelligence,” said Klupar, citing Vannevar Bush.

Astronomers are about to find out how smart both NASA and private organizations can be when it comes to space missions.

This article first appeared in the February 2026 issue of SpaceNews Magazine.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

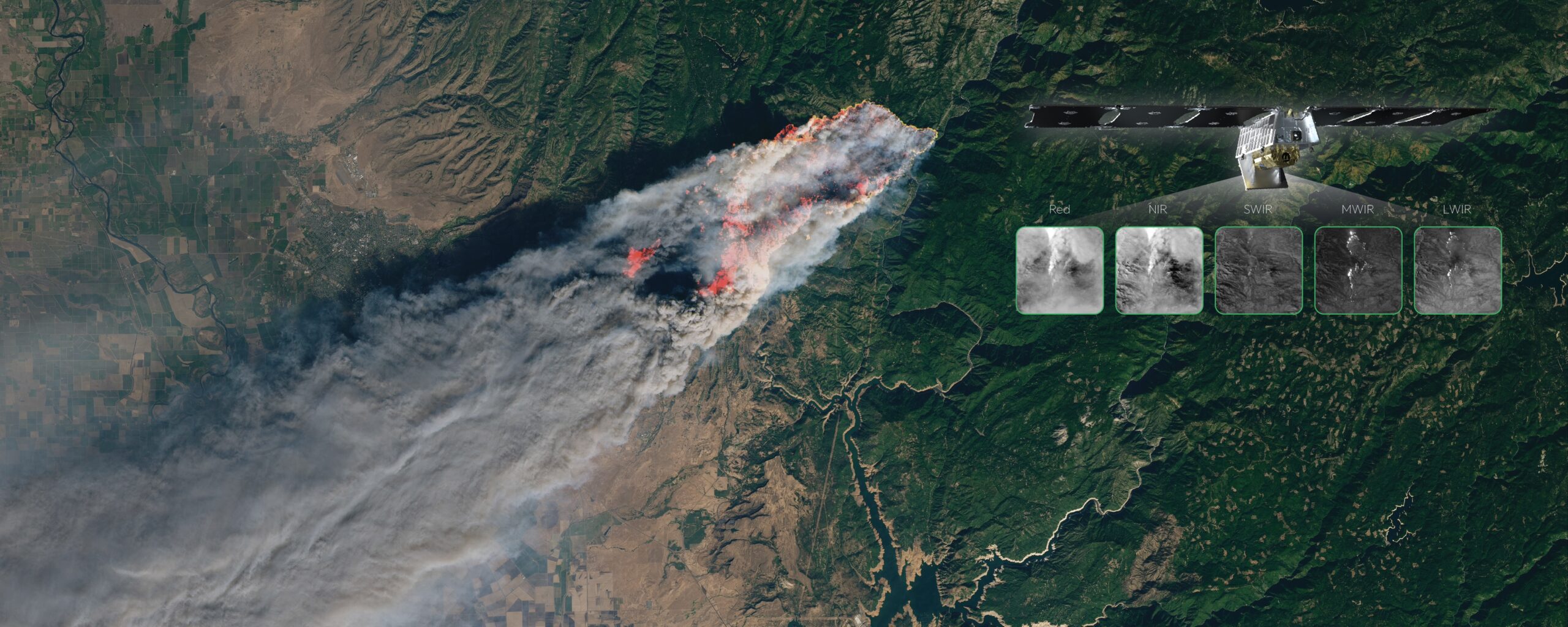

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly