Now Reading: Starlink and the unravelling of digital sovereignty

-

01

Starlink and the unravelling of digital sovereignty

Starlink and the unravelling of digital sovereignty

In January 2026, Iranian authorities shut down landline and mobile telecommunications infrastructure in the country to clamp down on coordinated protests. Starlink terminals, which were discreetly mounted on rooftops, helped Iranian protesters bypass this internet blackout. The role played by Starlink in the recent Iranian protests challenges the notion of digital sovereignty and promotes corporate entities to controversial arbiters in international political conflicts.

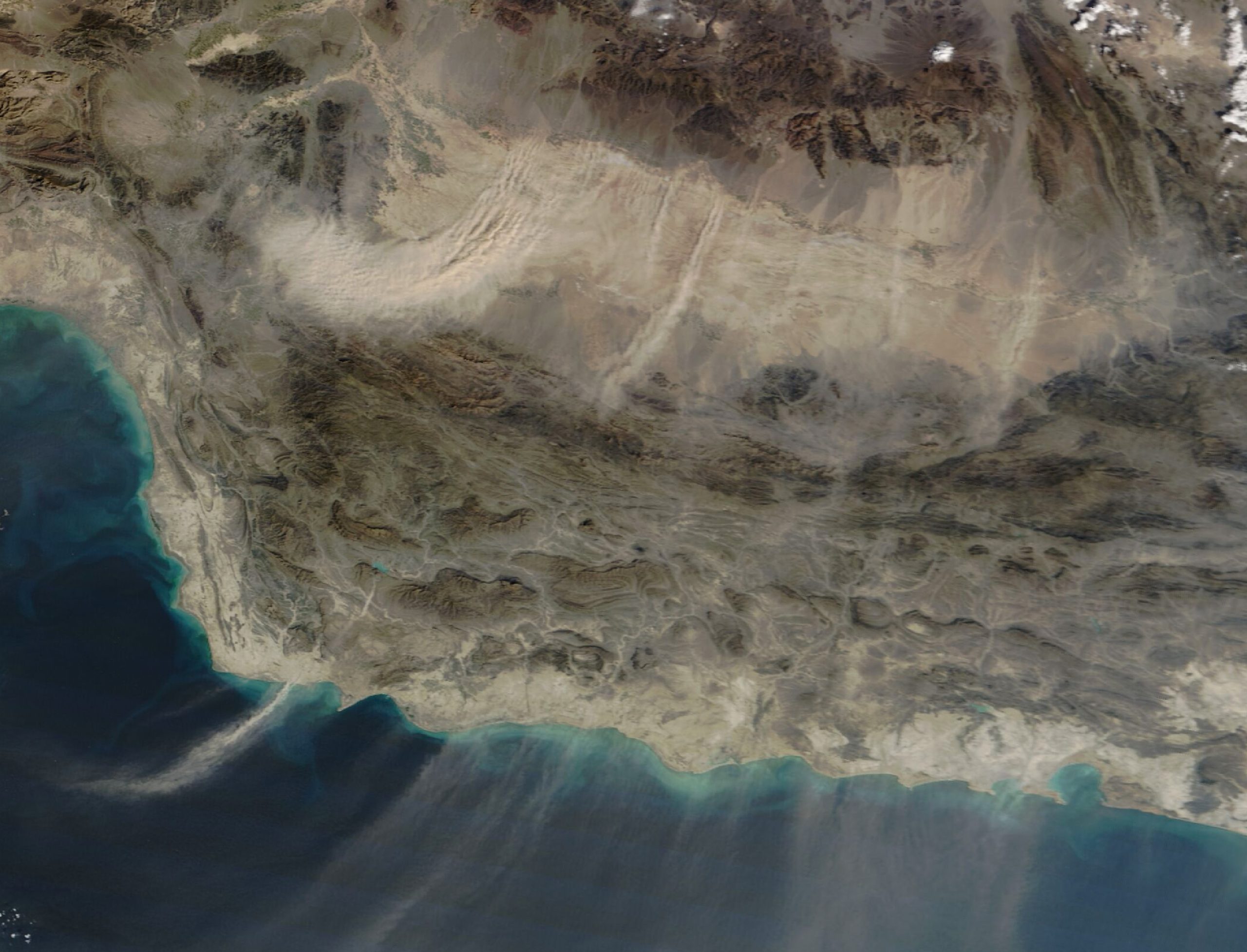

The Iranian government’s internet shutdown was unprecedented in terms of scale and sophistication. Though, since 2022, thousands of Starlink terminals had been smuggled through border routes or aboard clandestine vessels traveling through the Gulf. These terminals constructed an ad hoc network which became the only reliable way of streaming video and photographic documentation of the unrest. While authorities in any state can cut cable internet, Starlink has no such infrastructure tethered to it and as such, it served as a lifeline for protesters to disseminate information and coordinate collective action.

In response, international technical analysts reported military grade jamming and GPS spoofing by Iranian authorities that degraded Starlink service in specific localities. The struggle over accessing the internet between the protesters, SpaceX engineers, and Iranian security forces became an example of how the state monopoly of information flows may be weakening. Although Iranian law enforcement could use drones to track down terminals and threaten up to 10-year sentences for unauthorized use, they could not entirely block signals sent to and from Starlink satellites. It thereby reflected the sentiment of Elon Musk four years earlier, when Starlink became operable in Afghanistan: authorities opposing Starlink in any state could just shake their fists at the sky.

In this context, while the technological dimensions of Starlink’s role in Iran are important, its geopolitical implications are deeper. While Starlink has been used as a vital tool in humanitarian crises, and has in many cases saved lives, the intervention in Iran was not an apolitical humanitarian gesture. It became a geopolitical tool when President Trump stated that he would ask Elon Musk and SpaceX to circumvent Iran’s internet blackout. SpaceX then started waiving fees for Iranian users, effectively turning a commercial service into what could be perceived as a militarized tool of foreign policy by non-United States allies.

This incident of privatized diplomacy raises troubling questions regarding accountability as a company responsible to shareholders, not voters, decides which beleaguered populations are to receive a digital lifeline. A similar scenario was observed in Venezuela days before the Iranian internet blackout. Starlink provided a month of free service following the U.S.’s capture of the country’s head of state. It is concerning to think of the novel power dynamics that such a precedent engenders.

The same dynamic may now reappear in different regions around the world in times of crisis. The Iranian case is especially fraught since the government had imposed a sovereign internet blackout but its enforcement was impeded by SpaceX. Many states which were in the process of issuing Starlink licenses, will now be cautious of how doing so might undermine their sovereign control of communications someday.

Last year, Srilanka had stalled the rollout of Starlink in view of the same concern. Such considerations might similarly complicate future licensing of Starlink as well as other emerging satellite constellations. Iran’s complaints to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) since 2022 have revealed the insufficiency of the existing international frameworks to tackle this challenge; the ITU had ruled in Iran’s favor and concluded that Starlink was operating in Iran illegally. Yet it could do nothing about it.

The Starlink phenomenon thus poses technical and philosophical dilemmas. Does it democratize the right to resist or corporatize digital sovereignty? On one hand, it gives citizens the power to challenge a state’s monopoly on information flows, and is a powerful counterbalance to authoritarianism. On the other hand, it concentrates power in the hands of the private sector that creates dependency and leads to opaque lines of influence beyond sovereign control. The duality of Starlink is underscored by the fact that the same service that allowed vital information flows from Iran to the outside world has also facilitated the operation of scam centres in Myanmar, and it can be turned off at the whim of a CEO, as was the case in Ukraine.

January 2026 could thus mark a turning point at which satellite internet went from being a novel connectivity solution to heralding a future where the internet will no longer be a global commons. Rather, it might be a contested space where nation states, technology conglomerates and citizens compete for influence and control. No actor will hold total sway over accessing or curbing digital signals being sent or received from space. Looking ahead, the critical question is not just how to maintain a source of digital light in times of imposed darkness or military disaster. The pressing issue is whose hands will turn the switch and under what laws, whether human, market or moral, will those hands be held to account.

Mustafa Bilal is a research assistant at the Centre for Aerospace & Security Studies (CASS), Islamabad.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion (at) spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. If you have something to submit, read some of our recent opinion articles and our submission guidelines to get a sense of what we’re looking for. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent their employers or professional affiliations.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly