Now Reading: Sun erupts with powerful X-class flare as huge CME races toward Earth, impact possible within 24 hours

-

01

Sun erupts with powerful X-class flare as huge CME races toward Earth, impact possible within 24 hours

Sun erupts with powerful X-class flare as huge CME races toward Earth, impact possible within 24 hours

The sun sure has woken up this week, unleashing a powerful X-class solar flare along with a fast Earth-directed coronal mass ejection (CME), which is currently forecast to hit Earth within the next 24 hours.

Space weather forecasters are busy analysing data and running models to narrow down the CME’s arrival window.

Why the CME’s impact depends on its magnetic orientation

CME arrivals are notoriously difficult to forecast. Their speed, direction of travel and — most importantly — their magnetic orientation all determine how strongly (if at all) they will interact with Earth’s magnetic field.

If the CME’s magnetic field is oriented southward, a component known as the Bz, it can more easily link up with Earth’s northward-pointing magnetic field, allowing energy to pour into our planet’s magnetosphere and trigger geomagnetic storm conditions.

If the Bz is instead oriented northward, Earth’s magnetic field largely deflects the incoming energy, effectively “closing the door,” and what looked like a promising space weather event can end up being a bit of a nothing burger.

Some CMEs contain a mixture of southward and northward magnetic fields, which can lead to stop-start or fluctuating geomagnetic activity. These events keep space weather forecasters and aurora chasers very much on their toes.

We won’t know the CME’s true magnetic orientation until it is much closer to Earth, when it will be sampled directly by solar wind monitoring spacecraft positioned upstream of our planet, such as DSCOVR and ACE.

What’s an X-class solar flare?

Solar flares are ranked in ascending strength from A, B, C and M up to X, with each letter representing a tenfold increase in intensity. X-class flares are the strongest eruptions and the number following the X indicates how powerful the event is. Today’s flare was measured at X1.9, putting it in the upper tier of solar outbursts.

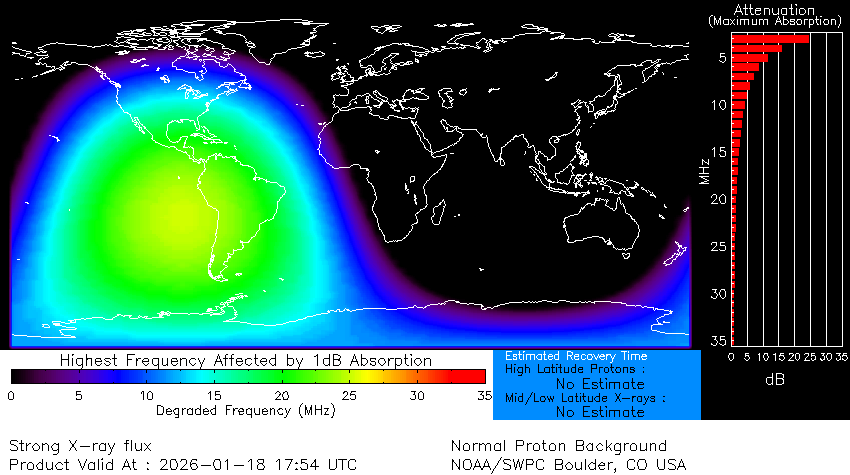

The powerful flare from sunspot region AR4341 peaked at 1:09 p.m. EST (1809 GMT), according to NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center. The eruption triggered strong (R3) radio blackouts across the sunlit side of Earth, with the most severe disruptions concentrated over the Americas.

What is a CME and how can it affect Earth?

A CME is a massive expulsion of plasma from the sun that carries a magnetic field. If a CME hits Earth’s magnetosphere — the protective magnetic “bubble” generated by our planet — it can trigger a geomagnetic storm.

These geomagnetic storms vary in intensity and are therefore classified on a scale from minor (G1) to extreme (G5). Current forecasts from the U.K. Met Office suggest the incoming CME could produce strong (G3) to severe (G4) geomagnetic storm conditions.

Storms of this magnitude can disrupt satellite operations, degrade GPS navigation and increase atmospheric drag on spacecraft. They can also supercharge auroral activity, potentially pushing the northern lights far beyond their usual high-latitude haunts and into mid-latitude regions near 45° latitude.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly