Now Reading: Taiwan’s Moonshot: why ‘T-Dome’ needs systems engineering, not just a shopping list

-

01

Taiwan’s Moonshot: why ‘T-Dome’ needs systems engineering, not just a shopping list

Taiwan’s Moonshot: why ‘T-Dome’ needs systems engineering, not just a shopping list

When President John F. Kennedy stood before Congress in May 1961 and declared that the United States would land a man on the moon before the decade’s end, his purpose was not to invent the space program, but to impose a clear objective, a deadline and the resources to unify these efforts. The success of NASA’s Moonshot would ultimately hinge not on any single breakthrough in rocketry, but on the disciplined application of systems engineering that integrated thousands of technologies, requirements, interfaces, fabrication and tests into a coherent, reliable whole. Without that organizing framework, the ambition Kennedy articulated would have remained a vision rather than a reality.

Taiwan’s T-Dome: a program name without a program plan

Fast-forward to October 2025 in Taiwan, when its President Lai Ching-te announced that the country must increase defense spending, framed as a climb toward 3% of GDP in the near term and 5% by 2030. Lai also created a new program: “T-Dome,” an integrated air-and-missile defense system meant to protect the island country from the Chinese People’s Liberation Army.

In engineering terms, a dome is a probabilistic defensive envelope. Israel’s Iron Dome is the obvious reference point. The U.S. has its own brand-name equivalent, the “Golden Dome,” an ambitious missile defense vision tied to space sensors and interceptors.

Taiwan’s defense acquisition has long depended on the U.S. This reliance risks encouraging military and political leaders to conceptualize Taiwan’s T-Dome challenge as a solvable shopping list — buy a proven system, plug it in and sleep better. But T-Dome is not something Taiwan can buy; it is something Taiwan must engineer. The island country’s threat environment is not the same as that of Israel or the U.S. Instead, in important ways, it is more complicated than both.

Why “Dome” analogies could mislead

Israel primarily faces a high volume of low-cost, unguided artillery rockets from non-state actors, such as Hamas and Hezbollah, and a limited number of ballistic missiles from Iran and Houthis rebels. The U.S. faces a bifurcated threat: continental defense against intercontinental ballistic missiles from rogue states and peers, and force protection against the possibility of China’s targeting forward bases like Guam.

In stark contrast, Taiwan faces saturation from a continental superpower. China, located just 100 miles away, can launch a coordinated, large-scale strike involving ballistic and cruise missiles, long-range rockets, hypersonic vehicles, glide bombs, warplanes and proliferated unmanned systems. Beyond strike assets, China can integrate space-based surveillance, electronic warfare and cyber operations into the campaign. Taiwan, with minimal strategic depth and sharply compressed warning time, would face a level of scale, integration and technological sophistication that far exceeds that of Israel’s adversaries.

From “acquire and deploy” to system of systems

Much of what Taiwan calls “technology transfer” has consisted of acquired-and-deployed fighters, missiles, radars, tanks and platforms bundled into foreign sales packages. That approach made sense when the priority was to catch up on discrete capabilities.

But a modern “T-Dome” is not a single capability. It is a system of systems: layered sensors across ground, air and space; diverse effectors ranging from interceptors and electronic warfare to decoys and hardening; resilient, multi-path, anti-jam communications; robust command and control (C2) incorporating real-time data fusion and battle management; and, critically, a doctrine for counterstrike while under sustained attack.

Here, Taiwan confronts a self-inflicted constraint: Its defense industrial base, monopolized by a handful of state-owned enterprises, has provided very limited pathways for private-sector participation at scale. Taiwan is fully capable of building world-class hardware as its commercial ecosystem demonstrates. But defense-grade systems development demands more than components. Systems engineering, integration and operational testing have not historically been Taiwan’s industrial strengths, primarily because the defense sector has not been structured to demand, reward or institutionalize these capabilities.

Define success in operational terms, not procurement totals

If T-Dome is evaluated solely by the number of interceptors procured, it will be futile. But if it becomes an engineering program measured by how quickly Taiwan can sense, decide and act under jamming, deception and destruction, then it offers a genuine fighting chance.

Before Taiwan decides what to build, it must do the groundwork that is least photogenic and most decisive: system-of-systems engineering analysis using state-of-the-art tools. This entails rigorously modeling threat vectors and salvo dynamics; geography and terrain masking; mobility and dispersal; sortie generation and regeneration; magazine depth and reload rates; C2 and communications resilience; logistics and sustainment; repair under fire; and human decision timelines. Then stress-test candidate T-Dome architectures against various scenarios.

This is not an academic exercise. If Taiwan does not rigorously identify where its systems bend or break under that pressure, it risks investing scarce resources in the wrong solutions.

Build a distributed sensing-and-decision network

Taiwan must move beyond its current buy-test-fix approach and adopt the model-analyze-build paradigm commonly used by global aerospace and defense firms. The transition to digital engineering and model-based systems engineering enables virtual iteration, using digital twins to optimize integrations before the hardware is built. Only by institutionalizing these engineering disciplines — with targeted assistance and technology transfer from the U.S. — can Taiwan transform its defense sector from a purchaser of symbols into an integrator of resilient deterrents.

Therefore, T-Dome should be a distributed sensing-and-decision network rather than a few exquisite nodes. Deploy many modest, mobile apertures — multi-band truck-mounted phased arrays that radiate intermittently — plus passive and multi-static radars to frustrate enemy electronic surveillance. Backstop with unmanned airborne sensing and space cueing, so losing any single sensor does not collapse the system.

C2 under saturation

In that context, Taiwan must stop viewing air defense as a static shield and start seeing it as a throughput-limited system governed by the laws of queueing theory. In the physics of high-intensity warfare, a centralized command center is also a single point of failure. When the C2 node functions as an overloaded server, as incoming tracks approach capacity, the system will suffer nonlinear delay spikes that break the “sensor-to-shooter” time budget.

The fix is distributed edge processing — push tracking, classification, and preliminary firing decisions to smaller nodes, while higher echelon C2 prioritizes and allocates scarce high-end interceptors, such as Taiwan’s indigenous Tian-Kung (Sky Bow) and U.S. Patriot missiles, against more destructive Chinese munitions. In a word, many moderately loaded C2 nodes are not only more survivable but also outperform a saturated large command center.

Source attack as a core stack

To blunt a saturation strike, Taiwan must transition from a reactive posture to a proactive one, in which find-and-strike operations against China’s mobile launchers serve as a primary layer of defense that thins the incoming. The mathematics of T-Dome will never favor the defender if attention is confined to increasing the “service rate” — the number of interceptors it can fire. Defense must also aggressively reduce the “arrival rate.” This requires integrating source attack as a core stack of the system: every mobile Chinese launcher neutralized inside China yields a multiplicative reduction in the saturation pressure the T-Dome must absorb.

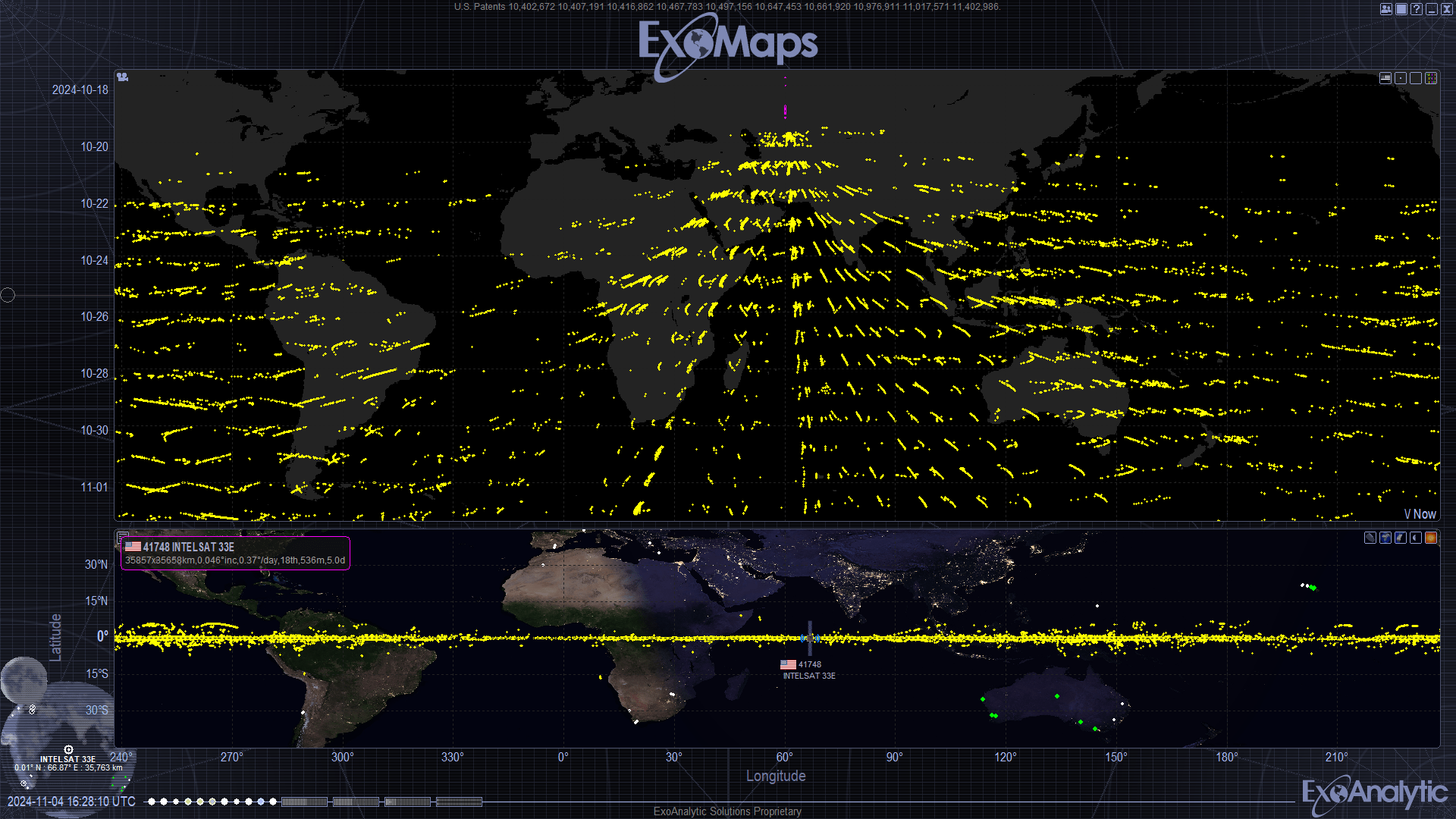

However, Taiwan’s most conspicuous gap lies in limited, scalable find-and-strike capability against mobile launchers, driven by the absence of persistent space and airborne sensors, fragile links from detection to authorization to fires and insufficient strike assets. The recent U.S. approval of ATACMS short-range ballistic missiles is a welcome step, but it is insufficient on its own, as effective employment also requires not only longer-range precision munitions but also real-time intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities.

The space-and-spectrum backbone

Taiwan’s military has historically neglected the criticality of electronic warfare. But jamming or spoofing China’s Beidou global navigation satellite system, on which China’s precision munitions rely — paired with resilient alternatives to GPS — could blunt Chinese strikes while simultaneously enabling Taiwan’s own attacks.

This approach, together with other electronic warfare measures and tactics, will succeed only if Taiwan controls the underlying know-how. True deterrence requires electronic sovereignty — ability to rapidly adapt software and threat libraries. Reliance on foreign vendors for updates during a Chinese blockade would be a recipe for failure, underscoring the urgent need for an indigenous electronic-warfare capacity capable of evolving faster than China’s military.

Mixed-cost defense portfolio

In practice, T-Dome must optimize cost and survivability as much as kinematics: a layered, mixed-cost intercept structure — expensive missiles for the hardest/highest-value threats, and abundant low-cost guns, jammers, spoofers, high-power microwave, lasers for mass raids — solving a weapons-to-targets assignment problem under finite inventories. Moreover, communications must be redundant: buried fiber, unmanned aerial relays, satellite links and high-frequency, directional, short-burst transmissions offer resiliency.

Equally important, logistics and recovery must be designed as combat power: prepositioning reloads, mobile rearming, protected fuel and power, clear interceptor allocation rules under constrained resupply, repairs, maintenance and reconstitution in minutes or hours, not days.

Internal reform is crucial

President Kennedy’s Moonshot succeeded not because he wrote a large check, but because NASA institutionalized the discipline of systems engineering. Taiwan’s President Lai has articulated a vision for T-Dome; now, the establishment must provide the discipline.

Deterrence begins at home, and it is maintained through engineering. Taiwan must recognize that external support is not a substitute for internal reform. This means modernizing the military mindset and the defense industrial base to prioritize system integration over the mere accumulation of hardware. Without this intellectual and industrial transformation, even the most advanced U.S. weapons will not be an effective deterrent. Like the Moonshot, T-Dome’s success will ultimately hinge not on a single system, but on the organizing framework that turns Lai’s ambitious vision into a combat-ready reality.

Holmes Liao has worked in the U.S. aerospace and defense industries for more than 35 years. Previously a distinguished faculty member at Taiwan’s War College, he is also the founder of Taiwan Advocacy, an organization dedicated to Taiwan’s security.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion (at) spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. If you have something to submit, read some of our recent opinion articles and our submission guidelines to get a sense of what we’re looking for. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent their employers or professional affiliations.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly