Now Reading: Tatooine exoplanets are oddly rare, and we finally know why

-

01

Tatooine exoplanets are oddly rare, and we finally know why

Tatooine exoplanets are oddly rare, and we finally know why

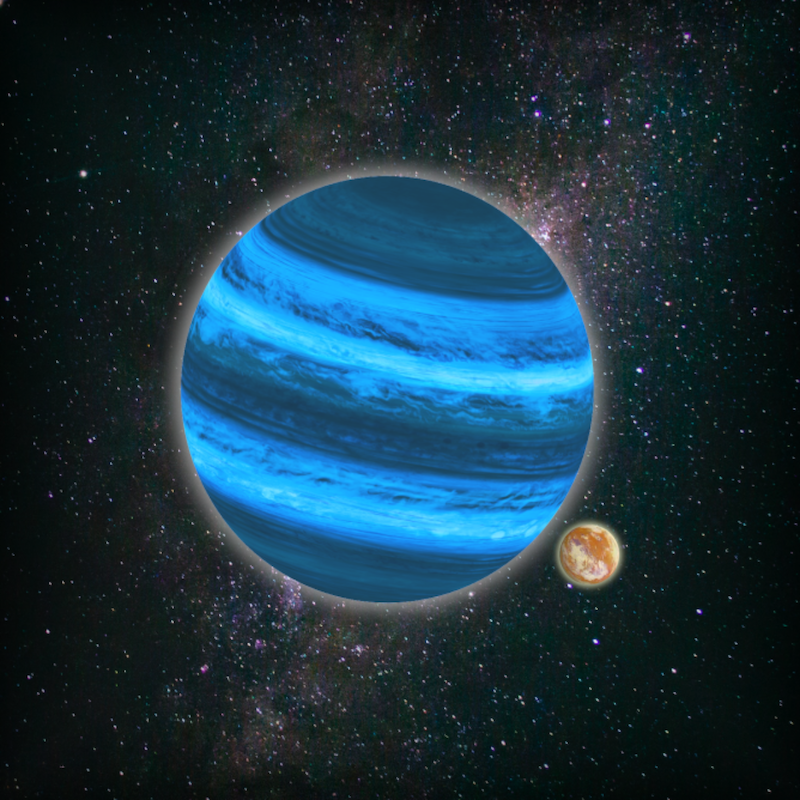

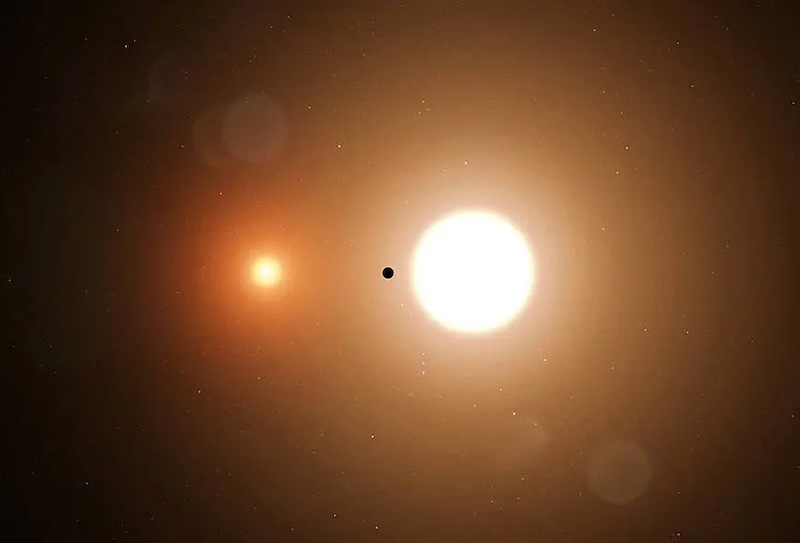

- Tatooine planets are exoplanets that orbit two stars instead of just one. The name comes from the fictional arid desert world in “Star Wars.”

- These planets seem to be rarer than first thought, although they do exist.

- Einstein’s general theory of relativity – specifically the gravitational effects of the two stars – is to blame for their rarity, according to a new study.

EarthSky’s 2026 lunar calendar shows every day’s moon phase. Get yours today!

Tatooine exoplanets are rare

In “Star Wars,” the planet Tatooine was remarkable because it orbited a pair of stars, not just one. And astronomers have found real examples of Tatooine worlds, called circumbinary planets. But they seem to be rare. Why? On January 30, 2026, scientists said Einstein’s general theory of relativity is to blame. Over time, the orbits of the two stars around each other shrink. As a consequence, the planet’s orbit becomes wildly elongated. Ultimately, the planet will either be consumed by one of the stars or get ejected from the system entirely.

The theory of general relativity basically says the observed gravitational effect between masses – such as a pair of binary stars – results from their warping of spacetime. It interprets gravity as a warping of the fabric of spacetime by a mass, similar to how a person on a trampoline warps the surface and makes other objects on the trampoline fall inward toward the person.

Astrophysicists at the University of California, Berkeley and the American University of Beirut in Lebanon published their peer-reviewed findings in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on December 8, 2025.

University of California, Berkeley: Why Are Tatooine Planets Rare? Blame General Relativity. news.berkeley.edu/2026/01/30/w…

— AAS Press Office (@press.aas.org) 2026-02-02T16:14:05.036Z

A dearth of binary star exoplanets

Astronomers had found massive exoplanets – like Jupiter and Saturn in our solar system – around 10% of single, sunlike stars. These were in the datasets from the Kepler and TESS space telescopes, about 300 planets overall. They had expected to find similar numbers orbiting binary stars also. However, they only found 47 candidate planets and 14 confirmed planets. Lead author Mohammad Farhat, a Miller Postdoctoral Fellow at UC Berkeley, said:

You have a scarcity of circumbinary planets in general and you have an absolute desert around binaries with orbital periods of seven days or less. The overwhelming majority of eclipsing binaries are tight binaries and are precisely the systems around which we most expect to find transiting circumbinary planets.

The instability zone

Binary star systems have an instability zone. This is a region where no planet can survive for long, and it ties in with the theory of relativity. The gravitational interactions of a planet and both stars can be chaotic. As a result, the planet will either be consumed or shredded by one of the stars, or it will be expelled from the system altogether. Indeed, 12 of the 14 confirmed planets orbiting close binary stars orbit just beyond the edge of this instability zone. This is why they are still safe. As Farhat explained:

Planets form from the bottom up, by sticking small-scale planetesimals together. But forming a planet at the edge of the instability zone would be like trying to stick snowflakes together in a hurricane.

General theory of relativity is to blame

The researchers found general relativity had a significant effect on planets orbiting binary stars. They calculated that eight out of 10 such planets would be disrupted in their orbits. And 75% of those would end up being destroyed. Why does this happen?

In binary star systems, the stars usually have similar, but not identical, masses. They orbit each other in elongated, egg-shaped orbits. If there is a planet orbiting both stars, the gravity from the stars will cause the planet’s orbit to precess, similar to how the axis of a spinning top wobbles. Precession is the slow gyration of the rotation axis of a spinning body around another line intersecting it.

The orbit of the planet Mercury also experiences precession. In fact, it’s slightly higher than predicted by the earlier theory of gravity by Isaac Newton. The additional precession is explained by the general theory of relativity.

2 possible fates of Tatooine exoplanets

The orbits of the two binary stars also undergo precession, due mostly to general relativity. The distance between the two stars gradually shrinks over time. As the precession rate of the stars increases, the precession rate of the planet slows down. Eventually, the two precession rates will match and become in resonance. As a result, the planet’s orbit becomes even more elongated. As Farhat explained, there are then two possible outcomes for the planet, neither of which are good:

Two things can happen: Either the planet gets very, very close to the binary, suffering tidal disruption or being engulfed by one of the stars, or its orbit gets significantly perturbed by the binary to be eventually ejected from the system. In both cases, you get rid of the planet.

Co-author Jihad Touma, a physics professor at the American University of Beirut, added:

A planet caught in resonance finds its orbit deformed to higher and higher eccentricities, precessing faster and faster while staying in tune with the orbit of the binary, which is shrinking. And on the route, it encounters that instability zone around binaries, where three-body effects kick into place and gravitationally clear out the zone.

Opposite effects of general relativity

Curiously, general relativity could stabilize some planetary systems, like Mercury, yet destabilize others, as Touma noted:

Interestingly enough, nearly a century following Einstein’s calculations, computer simulations showed how relativistic effects may have saved Mercury from chaotic diffusion out of the solar system. Here we see related effects at work disrupting planetary systems. General relativity is stabilizing systems in some ways and disturbing them in other ways.

Bottom line: Tatooine exoplanets – planets orbiting two stars – are less common than scientists first thought. A new study says Einstein’s general theory of relativity is to blame for their rarity.

Source: Capture into Apsidal Resonance and the Decimation of Planets around Inspiraling Binaries

Via University of California, Berkeley

Read more: Rare Tatooine world has a weird orbit around brown dwarfs

Read more: Tatooine exoplanets may be more habitable than we thought

The post Tatooine exoplanets are oddly rare, and we finally know why first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly