Now Reading: The countdown to clean orbits has begun with ESA’s Zero Debris Charter

-

01

The countdown to clean orbits has begun with ESA’s Zero Debris Charter

The countdown to clean orbits has begun with ESA’s Zero Debris Charter

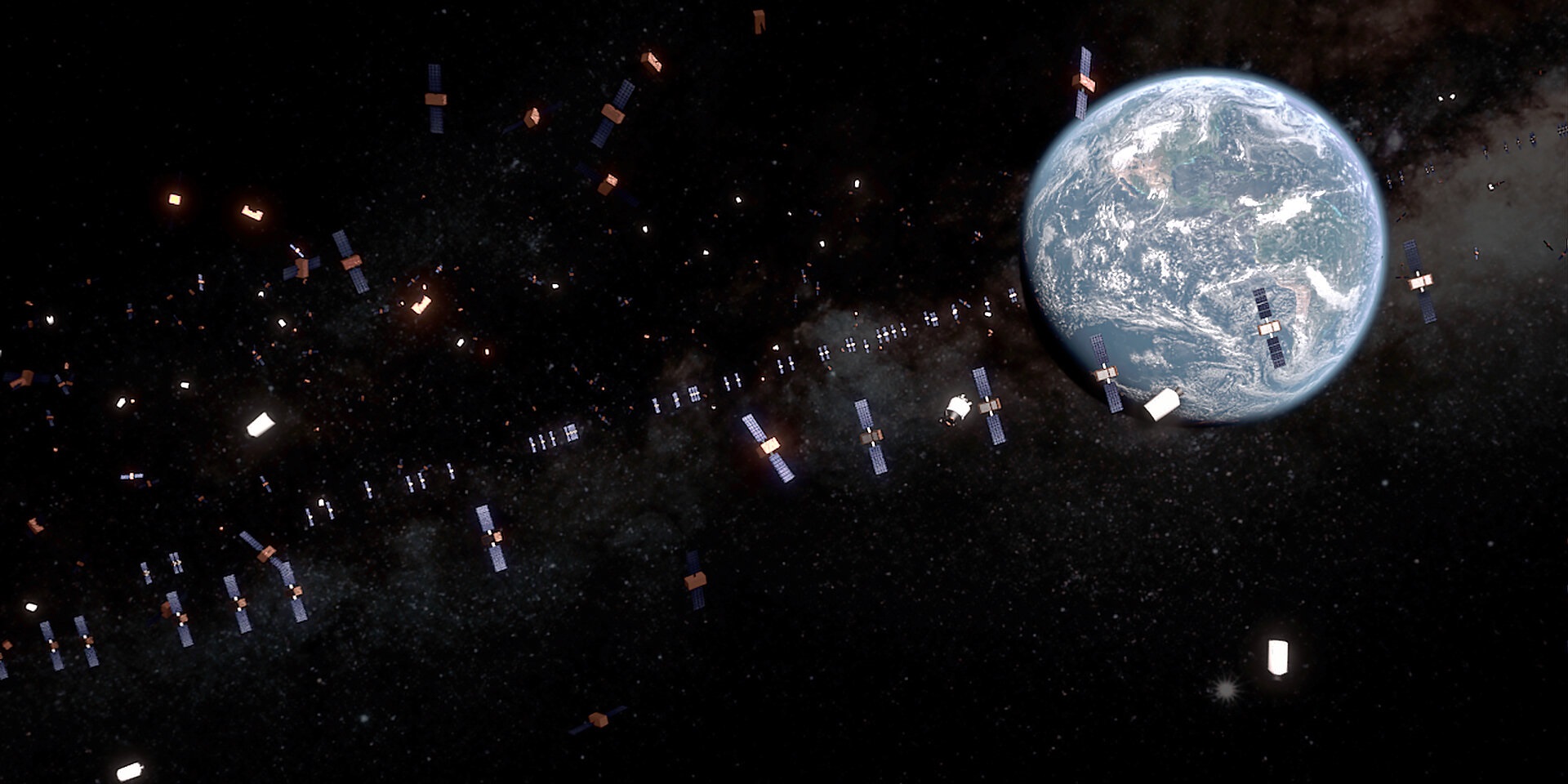

Space is rapidly becoming the world’s most congested frontier. What was once a domain of scientific exploration is now a crowded commercial arena, a global infrastructure layer critical to communications, navigation, climate monitoring and defense. Yet this dependence is threatened by a growing, largely invisible hazard: orbital debris.

The European Space Agency’s Zero Debris Technical Booklet is an ambitious and welcome step toward solving this problem. It offers a framework for achieving a debris-neutral orbital environment by 2030, outlining the technical priorities needed to safeguard access to space for generations to come.

But strategy and policy alone are not enough. Delivering the Zero Debris Vision will depend on industry’s ability to move from commitment to capability, from regulation to real-world implementation.

The scale of the challenge

The data tells a stark story. The number of active satellites orbiting Earth is projected to surge from 12,000 today to over 40,000 by the early 2030s, with each new launch into orbit increasing the risk of collision exponentially.

Current estimates put annual losses from space debris collisions at $100 million, most occurring between 600 and 900 kilometers of altitude, the same orbital band where much of our critical infrastructure resides. By 2030, this figure could exceed $1 billion per year, demonstrating that this problem is only set to grow in scale.

And even if humanity were to stop launching new satellites tomorrow, orbital debris would still multiply for years to come. Over 140 million fragments smaller than one centimeter now orbit Earth, joined by more than 1.2 million between one and ten centimeters in size. Only a tiny fraction, roughly 1%, can be tracked with any reliability. These may seem small and insignificant, but they are anything but. For instance, a clear example from the European Space Agency reported a 7 mm chip was found in one of the windows on the International Space Station’s Cupola, caused by “a tiny piece of space debris, possibly a paint flake or small metal fragment no bigger than a few thousandths of a millimeter across”. This is clear proof that these micro-fragments are not just a theoretical risk; they are hitting operational spacecraft and leaving lasting damage as we speak.

This means that most of the threat is invisible to us on Earth, and the industry remains heavily reliant on theoretical models rather than sustained, in-orbit observation. Without better data, policy enforcement becomes guesswork, and risk management becomes reactive instead of preventative.

From policy to practice: a systems approach

ESA’s Zero Debris Vision sets six priority goals: preventing debris release, ensuring clearance at end-of-life, preventing break-ups, improving surveillance, avoiding ground casualties and mitigating adverse consequences. These are not abstract aspirations; they are engineering and operational challenges that must be met with measurable solutions.

Meeting these goals requires a systems approach that combines prevention, protection and prediction:

- Prevention through responsible design, modular architecture and reliable de-orbit systems.

- Protection through lighter, smarter shielding and redundancy to limit fragmentation.

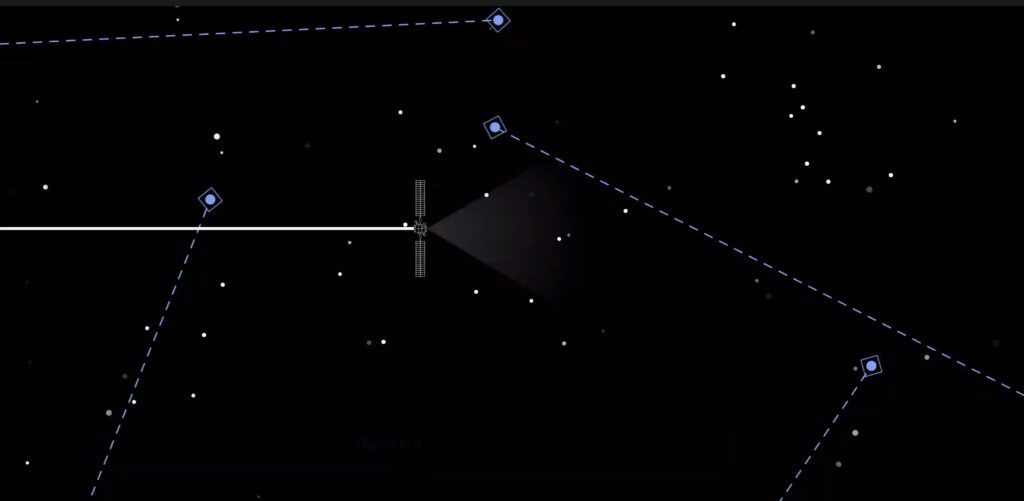

- Prediction through real-time situational awareness and in-orbit measurement of debris density and trajectory.

The path to zero debris lies not in any single technology but in the integration of these capabilities and a satellite network capable of detecting and avoiding trackable threats while withstanding untrackable ones will create true orbital resilience.

This technological ecosystem must be underpinned by transparent data-sharing frameworks and open innovation partnerships, linking commercial, defense and scientific stakeholders. The challenge cannot be solved by any one organisation or agency; it will take a coalition of innovators working toward a shared operational goal.

Economics of debris: the cost of inaction

In the aerospace industry, the financial stakes are high, and not limited to spacecraft operators alone. The space insurance market offers a clear warning. Out of roughly 13,000 active satellites, only about 300 are insured, and most collision-related losses are excluded from coverage. When unquantified risk dominates, insurers pull back, premiums spike and investor confidence erodes.

During the 2018/2019 insurance crisis, underwriters paid out more than they earned, forcing some to withdraw from the low Earth orbit (LEO) market altogether. The message was clear: without reliable data and improved survivability, space is uninsurable.

The economic case for action is therefore overwhelming. Investment in orbital debris prevention and protection yields exponential returns by reducing insurance volatility, enabling sustained private investment and ensuring that access to space remains commercially viable.

Conversely, the cost of inaction is existential. If certain orbits become too hazardous to use, global communications, navigation and Earth observation could be disrupted for decades.

OECD modelling indicates that a Kessler Syndrome event could inflict $191 billion in immediate global losses, while broader economic forecasts estimate sustained long-term damage of roughly 1.95% of global GDP.

Policy alone won’t get us there

ESA’s leadership has galvanised the global conversation, but funding and implementation lag far behind the scale of the problem.

National budgets tell the story. The UK Space Agency’s 2025/26 plan, for instance, allocates only 4 million pounds ($5.37 million) to In-Orbit Servicing, Assembly and Manufacturing. That’s less than 1% of its total budget despite identifying it as key to space sustainability. Across Europe, similar funding asymmetries persist between strategic rhetoric and technological execution.

To close this gap, policymakers must embrace dual-use innovation, recognizing that technologies developed for defense, communications or lunar exploration can also underpin debris mitigation and orbital safety. Conversely, space-safety technologies should be recognised as serving national security and industrial strategy objectives.

Funding models must evolve beyond linear grants toward hybrid public-private frameworks that incentivise operational deployment. Space debris management is a public good, but it will only scale sustainably through private sector participation and market mechanisms.

The next 24 months: a critical decision window

The next two years will determine whether the world achieves ESA’s 2030 target or misses it by a generation. The urgency is compounded by the exponential growth of megaconstellations and thousands of satellites being launched into already crowded orbital lanes.

This expansion is both opportunity and risk. Each new network brings global connectivity, but also raises the probability of collision cascades that could lock humanity out of LEO entirely.

If industry acts now, deploying measurement instruments, refining shielding systems, sharing data, and standardising end-of-life procedures, the 2030 milestone remains achievable. If not, the orbital commons may degrade beyond repair.

The time to act is now

ESA’s Zero Debris Vision offers more than a regulatory target, it represents a test of global innovation, collaboration and moral responsibility. The technology exists. The knowledge exists. What’s required is the collective will to fund, integrate and deploy it at speed.

The orbital environment humanity inherits in 2030 will be the direct consequence of choices made in the next 12 to 24 months. The window for preventative action is closing fast.

Achieving a debris-neutral future will not happen through policy statements or conference declarations. It will happen when industry leaders, agencies, and governments align resources and act decisively to transform science fiction into strategy, ensuring space remains a sustainable, secure domain for all.

Richard Jacklin is the commercial lead for space at Plextek.

James Snape is the founder of Aphelion Industries.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion (at) spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. If you have something to submit, read some of our recent opinion articles and our submission guidelines to get a sense of what we’re looking for. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent their employers or professional affiliations.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly