Now Reading: The curious case of why methane spiked around Covid

-

01

The curious case of why methane spiked around Covid

The curious case of why methane spiked around Covid

06/02/2026

1110 views

24 likes

With fewer cars on the road, planes in the air and factories running, the skies seemed cleaner during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, while there was a decline in pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide, scientists were surprised to see that methane surged in the early 2020s and then dropped – and now they know why.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas and is the second-largest contributor to climate warming after carbon dioxide.

A tonne of methane, despite its shorter lifespan of about 10 years in the atmosphere, can retain about 30 times more heat than a tonne of carbon dioxide over the course of a century. This means that when it comes to warming our planet, methane is a potent player.

Between 2020 and 2022, global concentrations surged at the fastest rate ever recorded, peaking at 16.2 parts per billion per year, before easing back to 8.6 ppb per year by 2023.

Using methodologies developed within the European Space Agency’s Climate Change Initiative’s RECCAP-2 project, a new international study, published in the journal Science, reveals why.

For a brief period, the atmosphere became less efficient at cleaning methane away – just as natural emissions from wetlands surged under unusual climatic conditions.

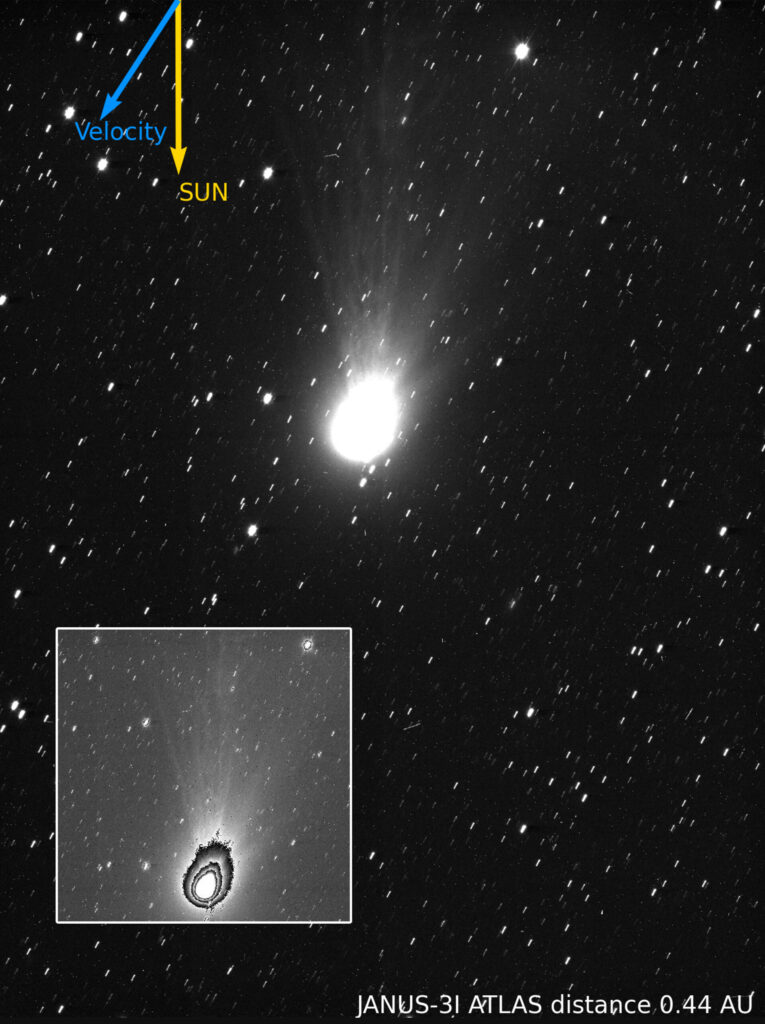

Philippe Ciais, from France’s Laboratory for Climate and Environmental Sciences (LSCE) and lead author of the paper, explained, “Our research combined satellite data, ground-based measurements, atmospheric chemistry data and advanced computer models to reconstruct the global methane budget from 2019 to 2023.

“The results point to a powerful and temporary shift in atmospheric chemistry as the main driver of the methane spike.”

At the heart of the story are hydroxyl radicals – highly reactive molecules often described as the atmosphere’s ‘detergent’. These radicals normally break down methane, limiting how long it remains in the atmosphere.

During 2020–2021, however, hydroxyl radicals levels around the world dropped. This is because the ingredients needed to make them were reduced when human activity slowed down.

Hydroxyl radicals form through chemical reactions involving sunlight, ozone, water vapour and gases such as nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide and volatile organic compounds.

As a result of the Covid-19 lockdowns, the emission of these gases dropped, and hence the hydroxyl radicals, which would normally destroy methane, also reduced – slowing the atmosphere’s ability to remove methane.

According to the study, this weakening of the atmosphere’s oxidising capacity explains around 80% of the year-to-year variation in methane growth over the period.

With fewer hydroxyl radicals available, methane accumulated faster than usual.

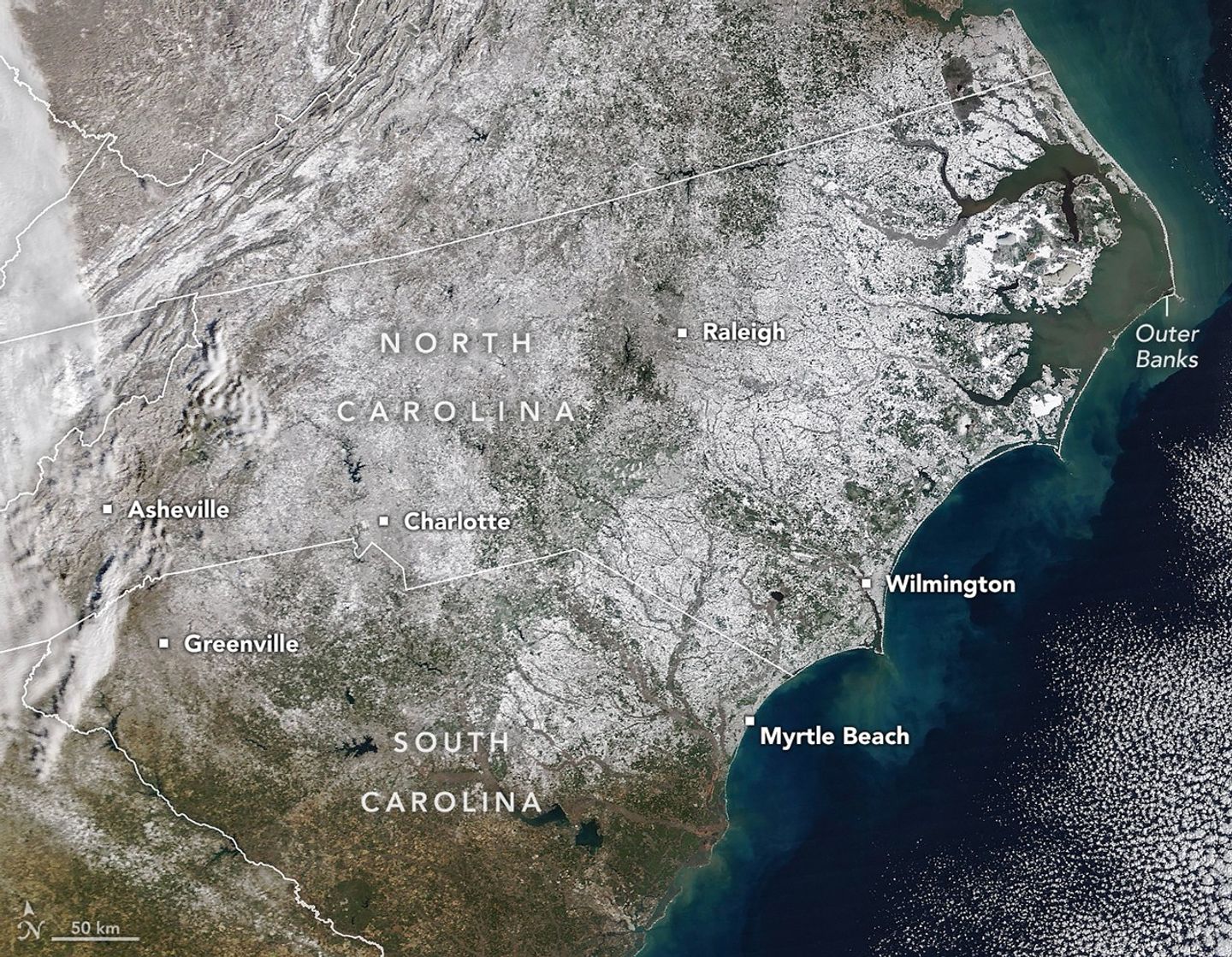

This chemical slowdown coincided with major changes in the climate. An extended La Niña phase from 2020 to 2023 brought wetter-than-average conditions across much of the Tropics.

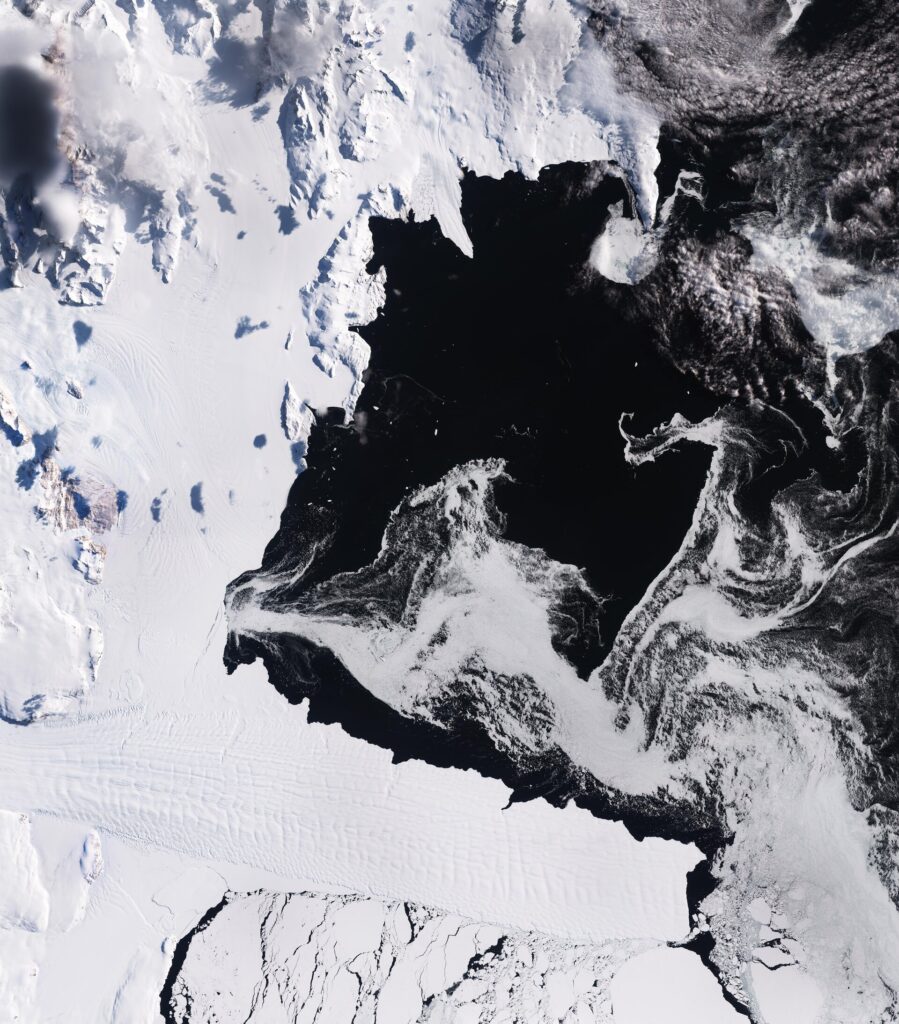

Flooded soils and expanded wetlands provided ideal conditions for methane-producing microbes, boosting emissions from wetlands and inland waters. The largest increases were seen in tropical Africa and Southeast Asia, while Arctic wetlands and lakes also released more methane as temperatures rose.

In contrast, South American wetlands showed a sharp drop in emissions in 2023, linked to extreme El Niño-related drought.

Crucially, the study finds that fossil fuel emissions and wildfires only played a minor role in the surge. Isotopic fingerprints in atmospheric methane instead point strongly towards microbial sources – wetlands, inland waters and agriculture – as the dominant contributors to the observed changes.

The findings expose important gaps in current methane emission models, many of which underestimated emissions from wetlands during this period.

The authors highlight the need for better monitoring of flooded ecosystems, improved representation of soil and water processes, and closer integration of atmospheric chemistry with climate variability.

“By providing the most up-to-date global methane budget through 2023, this research clarifies why methane rose so rapidly – and why it has recently slowed,” added Philippe Ciais.

According to Clement Albergel, ESA’s Actionable Climate Information Section Head, “The study underscores the growing importance of satellites – not only for tracking greenhouse gases, but for revealing the subtle chemical processes that govern their fate in the atmosphere. It shows that climate surprises are not always about what we emit, but about how the atmosphere responds.”

The message is clear: future methane trends will depend not only on how well humanity controls emissions, but also on air-quality policies and climate-driven changes in the planet’s natural methane cycle.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly