Now Reading: The Orionid meteor shower peaks under dark, moonless skies next week. Here’s how to see it

-

01

The Orionid meteor shower peaks under dark, moonless skies next week. Here’s how to see it

The Orionid meteor shower peaks under dark, moonless skies next week. Here’s how to see it

If you happen to glimpse a “shooting star” before dawn during the next several days, there’s a good chance that what you saw was a fragment left behind in space by the famous Halley’s Comet. For it is during the third week of October that a meteor display spawned by the debris shed by Halley reaches its peak: the Orionid meteor shower.

The Orionids aren’t one of the year’s richest meteor displays. If the August Perseids and December Geminids can be considered the “first string” among the annual meteor showers in terms of brightness and reliability, then the Orionids are on the junior varsity team.

And this will be an excellent year to look for them, since the moon will arrive at new phase on Tuesday morning, Oct. 21 at the very same time that the Orionids are reaching their maximum and hence will not pose any hindrance at all for those watching for these fiery streaks during their prime predawn viewing hours. Perfect!

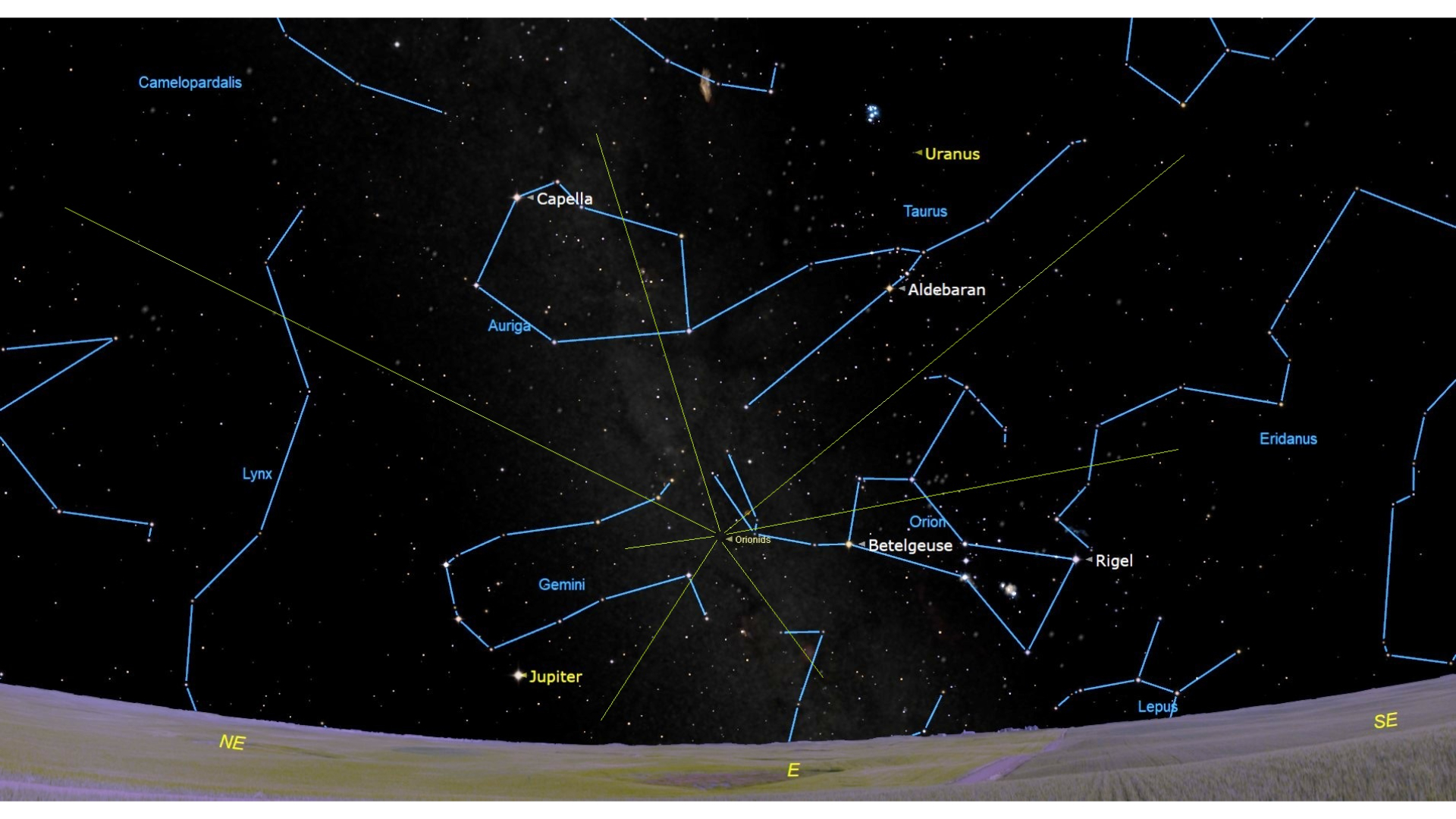

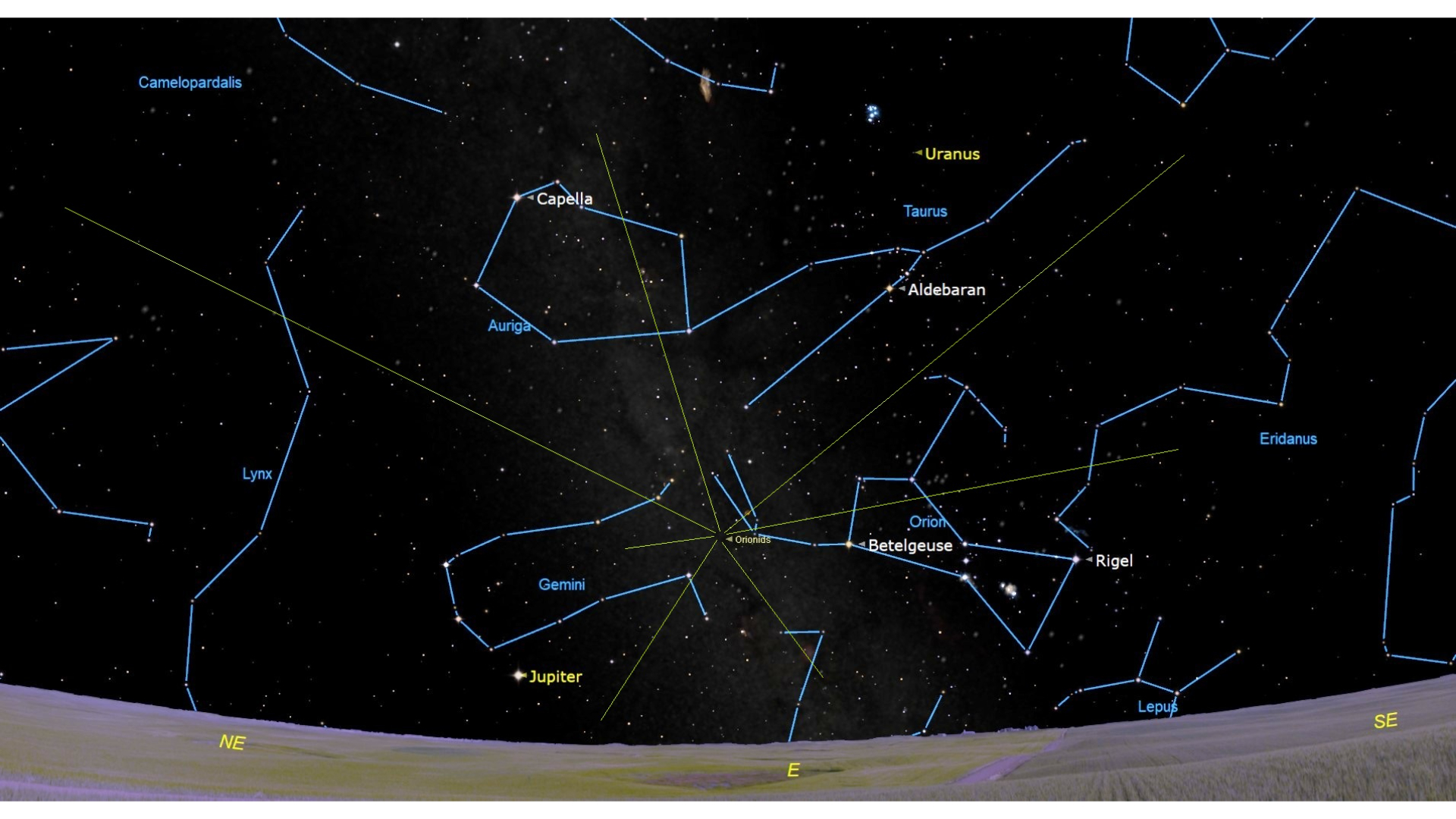

The meteor moniker “Orionid” comes from the fact that the radiant — that spot on the sky from where the meteors appear to fan out from — is just above Orion‘s second brightest star, ruddy Betelgeuse.

Orion, of course, is a winter constellation. At this moment, in early autumn, he appears ahead of us in our path around the sun, and as such has not completely risen above the eastern horizon until after 11:00 p.m. local daylight time. Several hours later, between 4 and 5:00 a.m. — Orion will be high in the sky toward the south-southeast. The higher in the sky Orion is, the more meteors will appear all over the sky. The Orionids are one of just a handful of known meteor showers that can be observed equally well from both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

But to see the greatest number of meteors, don’t look in the direction of the radiant, but rather about 30 degrees from it, in the direction of the point directly overhead (the zenith). Your clenched fist held at arm’s length is roughly equivalent to 10 degrees, so looking “three fists” up from Betelgeuse will be where to concentrate your view.

Halley’s legacy

As noted at the onset of this discussion, the Orionids have an illustrious lineage: Like the Eta Aquariid meteors of early May, they are bits of debris shed long ago by Halley’s Comet. The two showers are essentially one and the same; Earth intersects a single, broad stream of meteoroids at two places in its orbit on opposite sides of the sun. Typically, like the Eta Aquarids, Orionid meteors are normally dim and not well seen from urban locations, so it’s suggested that you find a dark (and safe) rural location to see the best Orionid activity.

“They are easily identified … from their speed,” write David Levy and Stephen Edberg in Observe: Meteors, an Astronomical League manual. “At 66 kilometers (41 miles) per second, they appear as fast streaks, faster by a hair than their sisters, the Eta Aquarids of May. And like the Eta Aquarids, the brightest tend to leave long-lasting trains. Fireballs are possible three days after maximum.” This aspect is undoubtedly connected in some way to the makeup of Halley’s Comet.

The shower is actually a complex of several sub-showers with different maxima spread over several days. Halley’s Comet’s last visit through the inner solar system was in the late winter of 1986 and it is due back in the midsummer of 2061. But each time it has swept past the sun — and it has done so probably countless hundreds, if not thousands of times — it has released tiny particles, mostly ranging in size from dust to sand grains, which travel near and along the comet’s orbit, creating a dirty trail of debris that has been distributed more or less uniformly all along its entire orbit.

The comet bits have also spread a fair distance from it sideways, which is why some of the particles now intersect the Earth even though the comet’s orbit does not. About the year 530 A.D. Halley’s orbit intersected that of the Earth. Presently, the least distance between the two orbits is 6,042,000 miles (9,710,000 km).

Observing tips

Orionid visibility extends from Oct. 16 to 26, with peak activity of perhaps 15 to 30 meteors per hour coming on the morning of Oct. 21. Step outside before sunrise on any of these mornings and if you catch sight of a meteor, there’s about a 75 percent chance that it likely is a by-product of Halley’s Comet. The last Orionid stragglers usually appear sometime in early to mid-November.

Be sure to bundle up very warmly; perhaps bring a sleeping bag. Find a dark spot with an open view of the sky. The less light pollution, the better; a shower like this one that’s rich in faint meteors is especially hard hit by artificial skyglow. The direction to watch is wherever your sky is darkest. Lie back, let your eyes adapt to the night, and be patient.

Good luck and clear skies!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky and Telescope and other publications.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly