Now Reading: The shift that saved American spaceflight

-

01

The shift that saved American spaceflight

The shift that saved American spaceflight

In this episode of Space Minds, former NASA commercial space division chief Phil McAlister sits down with host David Ariosto for a wide-ranging conversation about the future of human spaceflight, NASA’s internal culture, and the explosive growth of the commercial space sector.

McAlister spent nearly 20 years inside NASA, helping spearhead programs like Commercial Crew and COTS, which paved the way for SpaceX, Blue Origin, Rocket Lab, and a new era of public-private partnerships. He shares stories about internal resistance, political battles, and what it took to shift NASA away from cost-plus contracting after decades of inertia.

We also dive into:

• Whether the U.S. is really in a “space race” with China

• Why the moon’s South Pole may not be first-come, first-served

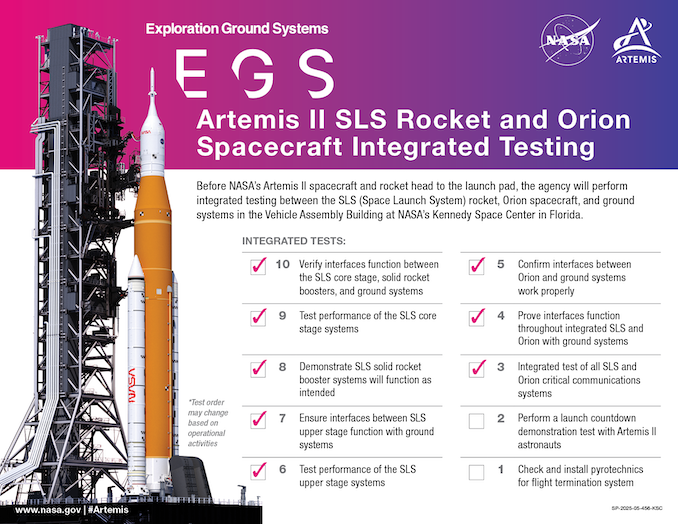

• The sustainability crisis facing SLS, Orion, and Artemis

• The role of commercial companies in deep space—not just LEO

• How Starship, New Glenn, and private human spaceflight change everything

• Whether NASA is destined to become more like the FAA

• What the next 50 years in space might actually look like

Show notes and transcript

Click here for Notes and Transcript

Time Markers

00:00 – Episode introduction

00:46 – Guest introduction

01:31 – Why Phil McAlister joined NASA

04:47 – The origins of Commercial Crew

07:44 – Internal resistance and “the old guard”

10:24 – Cost-plus vs. fixed-price contracts

12:24 – China, the moon, and geopolitical narratives

18:26 – The sustainability challenge for Artemis

25:47 – Commercial vs. government

28:36 – Will NASA become the FAA of space?

29:17 – Is NASA losing its magic?

35:36 – Why the commercial space is essential

Transcript – Panel Conversation

This transcript has been edited-for-clarity.

David Ariosto – Phil McAlister, NASA’s former, long-time commercial space division chief, thank you so much for joining us.

Phil McAlister – My pleasure.

David Ariosto – Yeah, you spent, like what, roughly two decades, give or take, at the agency, much of which was centered on commercial space and sort of the, you know, the emerging paradigm that we all now find ourselves in. And on your LinkedIn profile, you wrote “thankfully and blissfully retired,” so maybe that’s a good place to start in on all this and just reflecting, not only on your career, but I mean, gosh, you have seen sea changes within the nature of how we do business in space.

Phil McAlister – So that part was unexpected.

Phil McAlister – The whole reason I joined NASA, it was multifaceted. Of course, it wasn’t any one thing, but the primary thing that motivated me was I really felt like all the space markets that could potentially exist do exist. I really felt like private space travel was the one that really could revolutionize things.

Phil McAlister – And so, and I didn’t think at that time the private sector could do that solely on its own—orbital space transportation, human space transportation. I just felt like it was going to need some sort of government help. At that time, I wasn’t thinking public-private partnership, but I thought if anybody’s going to do this, it’s going to be NASA. And so that’s why I joined the agency in ’05, and that was the goal that motivated me through those 20 years.

And why I stayed so long. Actually, when I joined in ’05, Mike Griffin was the administrator, and I really thought I was just going to stay two or three years. I had been in the private sector before that, and I kind of wanted to check the box of government service, and I wanted to see if we could get something going on private space travel. And Mike lasted about three years, and at that time I almost left, but then Lori Garver came in. She was somebody that I had known and respected a lot in our previous careers. And a couple other people came in, and I was like, “Oh, well, let’s give this a little bit of… let’s give it a shot, see how long it can go.”

And then I became the Executive Director for the Augustine Committee, which was just a fascinating privilege. I know a lot of people say that about their careers, but it really was a privilege to work with Norm Augustine and Sally Ride. I got to meet Sally, and they endorsed a commercial crew—what ended up to be Commercial Crew. At that time, they didn’t call it that, and so I was hopeful then. And then in the President’s 2011 budget, the Commercial Crew Program was in there, and was funded and was structured in a way that I really thought could work because it was modeled after the COTS Program, and I oversaw the COTS Program, and I knew it could work. I could just foresee how we could apply those principles to human space transportation. And that’s what we did.

And that was super successful. 2020 is going to be forever etched in my mind as one of my career highlights when the SpaceX Dragon took Bob and Doug—Bob and Doug—to orbit into the International Space Station. And so along the way, just what happened—what you just said—was this sea change in NASA contracting, away from cost-plus and toward more fixed-price contracting, a change that I thought was overdue and very much welcome. Well, let’s start there.

David Ariosto – Let me—so let’s start in terms of, like, sort of the inception of all this. So, you know, you mentioned Augustine, that sort of led to the cancellation of the Constellation Program. It was sort of like a redefinition of how we were looking at spaceflight. And at that time, all this was coming on the heels of what happened in 2003 with Columbia. And, you know, years later, Challenger—speaking of which, Challenger, the anniversary, 40th anniversary, of Challenger’s coming up in January, which is just extraordinary.

I mean, if you think about it—how we did business then, how we’re doing it now, the nature of the shift and, you know, maybe sort of the baked-in ingredients of how you evaluate risk in terms of human spaceflight. I think that’s really interesting to dig in on in terms of the DNA that has been part of the NASA process—the “failure is not an option,” sort of Gene Kranz mindset.

And then you have, at this point—I mean, sort of leaping ahead a little bit—you have a commercial space sector that has a lot of founders with a Silicon Valley background. You talk Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, even Eric Schmidt with Relativity Space, in terms of his former days with Google. So I wonder how people think about this now: this fail-fast approach and how that relates to human space travel, and where we’re going with Starship. There are so many questions baked into this thing I’m not even quite sure where to begin, but maybe a good place to start is the inception of all this.

For an agency that’s been subject to back-and-forth and the to-and-fro of political leanings, the push toward commercial—I imagine at the beginning it might not have felt like the paradigm shift we’re experiencing now. Or did it? I mean, what was the environment like? What was the culture?

Phil McAlister – Well, so I guess there are two parts to that question. At the time, it was not a welcome change for NASA. I mentioned this to one of your colleagues: when the Commercial Crew Program was announced and we started it, I felt very strongly that it was the right thing to do. But I received—not just me personally, the program received—enormous pushback from what I will call the establishment or the old guard.

It was not a welcome change at all. NASA had been doing business basically the same way since the dawn of the space age—really, since NASA was created. These large, very process-oriented, traditional programs that used cost-plus contracts and traditional defense companies to do the work. And it took a long time. It was super expensive. There were consistently overruns, and I just felt like that was not a sustainable way of doing business.

You also still had some—

David Ariosto – Serious headwinds in terms of, just like, even Apollo luminaries—

Phil McAlister – Yes. Oh my gosh. Their opinions.

David Ariosto – “This is a pledge toward mediocrity,” I think was one of the quotes.

Phil McAlister – “We’re seeing the end of human spaceflight.” There was all sorts of rhetoric around that, and from people who were well-respected. And so it was—I went to war, basically, with the agency, to a certain extent, against the old guard, because it was something I felt so strongly about. And that was the goal—my single-focus goal.

And I mean, I wasn’t going to let anything stop me. I was almost fired multiple times—some of which were my own fault, but some of which weren’t—just trying to bring about this change. But it was long overdue, in my opinion. NASA had been doing business that way for 40 years when there was no commercial space industry at all, and really the only companies were big aerospace companies. And that all changed in the late ’90s, beginning 2000.

And so NASA had to change because our entire environment was changing, mostly because of the establishment of the commercial space industry. If NASA had had its way, it would have ignored it and kept doing things the same way. And we needed some real change agents—myself, Lori in particular, some other colleagues of mine internal to the agency. It wasn’t just me, even though I was very visible at the time. And we really had to fight against this.

And then, to be honest, David, after commercial cargo, I was getting a little worried that it would just be this one-off thing. Commercial Cargo was super successful. Then we got Commercial Crew. And I’m like, all right, the—

David Ariosto – Development of the SpaceX Dragon—the cargo transportation systems and the like. But crew is different.

Phil McAlister – Very much so. Crew is different.

David Ariosto – The politics are different. The risk tolerance is different.

Phil McAlister – Yes. And there’s astronauts, and that’s a big thing. It’s a big deal.

So I forget what I was saying… oh! So anyway, I was concerned it was going to be a one-off. And then we got Commercial Crew. It was super successful. I’m like, “Oh, well, now of course everything’s going to change, and we’re going to embrace the commercial space industry.” And we really didn’t. The agency really didn’t.

In my opinion, they moved away from cost-plus contracting, but they didn’t do it in a smart way— in a way that I felt the commercial space companies could succeed. We kind of ignored a lot of the lessons that Commercial Crew taught us. And I wrote this in one of my LinkedIn articles. I tried not to let this happen. I spent many hours giving lessons-learned discussions with my colleagues at NASA, doing knowledge-transfer videos and other things. I sent my personnel out to other projects to teach people within NASA how to do public-private partnerships and what the key ingredients were.

And I think, to a large extent, NASA did not embrace those—other than the move to fixed-price contracting, mostly because they had to, because we weren’t going to be able to afford to do much of anything the old way. In my opinion, SLS and Orion were sucking all the budget air out of the room.

And another one—well, we did do Gateway in this sort of weird way. But most of the other commercial initiatives, in my opinion, were incorrectly or inappropriately called commercial, and they just started using it as shorthand. And I fought against that. But ultimately, it’s one of the reasons I’m sitting here blissfully, thankfully retired—I really didn’t think NASA was going to embrace the commercial space industry. I was getting very pessimistic this time last year about how things were going to go.

And so I retired. This was before all the deferred resignations and retirements and all that. It was just time for me to go. And here it is, a year later, and my position still hasn’t been filled.

David Ariosto – So that’s, that’s sort of the sort of the broader question, I think, in all of this, and like in the context of, not only sort of this, there’s this push now that we’ve seen in almost, I mean, I think it’s safe to say it’s sort of an unprecedented fashion, at least in terms of the modality of what we’re approaching. Certainly, the 1960s was, was a different kind of push, but, but this one has one baked in terms of the the commercial applications. We see all these new, you know, endeavors that are happening, particularly in Leo, but not just, and it’s wrapped in this broader competition internationally, namely, namely Beijing, and you were there, you were there at the agency to kind of watch, maybe from afar, the maturation of that agency and merging as sort of a real rival to the United States and NASA. And I wonder in that context, where there’s like it was a degree of inevitability in terms of this push towards commercialism, given the nature of the ISS in the sense that’s set to retirement. It’s done its job, but by all accounts. But I mean, you know, within the course of less than five years that the plan is to de orbit this, I think it’s what the constant is, the largest piece of machinery ever put on orbit. And so, you know, China’s Chung space station is an operation. And I wonder, like, how you think about this in terms of not having that gap in Leo and not sort of seeding some of the sort of exciting science that can be talked on board, but also just the sheer presence of being there in, like, the ripple effects that has,

Phil McAlister – Yes, well, so I have kind of a contrarian view on that of I’m probably a contrarian. That’s why I took on commercial crew, right? Nobody wanted it, but, but me and a few others, but I took that on. And so when it comes to China and low earth orbit, my personal view is, I think all this rhetoric around making it a race, I think is misplaced and and I think if China were to get back to the moon, or to get there to the moon before we get back, I don’t think it’s going to be a huge deal. I think it’ll be a one week story, not a one day story, but a one week story, because it’s been done before. I mean, the whole reason why Apollo was so amazingly effective was because it hadn’t been done before. Super hard. Now, getting to the moon is hard. Ish, it’s not super hard. I don’t think we can say something super hard when we did it 50 years ago or 30 years ago, successfully. It’s hard ish, and it’s really expensive, but it, I don’t think it will have the resonance that it will now for them to get there before we get back. I think if they get there, we’ll say, hey, congratulations. Welcome to the welcome to the party. Don’t touch any of our stuff or what took you so long, right? And whoever’s in the, you know, whatever administration is in party, they’re going to blame the previous administration or the one before that. And I don’t, I think people are just going to move on, because I just don’t think it’s going to have the kind of resonance that it had in Apollo.

I don’t think a gap is any big deal. I don’t think people are really paying attention that much, the general public, and it’s really cool that we’ve had people in space continuously for 25 years. But if that were to, if there would be a hiccup in that for a few years, in the grand game of things, I don’t think it’s going to matter too much. So I wish people would just stop talking about this race with China, because we might not win. And if we just said, hey, we’re going to get there when we get there, if China happens to have a base there, that’s perfectly fine. China can’t take over the whole moon. They certainly can’t take over all of Shackleton Crater. That’s just ridiculous. It’s impossible.

So they could set up a base, we can set up a base. That’s what’s going to happen, inevitably, regardless of who gets there next. Or, you know, if they get there first, before we get back, we’re going to have two bases. They’re going to be, it’s China base. There’s going to be a US base in Shackleton. And I don’t think it’s really going to matter long term, who got there first. What’s going to matter is who can be there sustainably, and that’s why I think SLS Orion and Gateway have to go, because those are not, it’s just not sustainable. Everybody has said that. Everybody knows it. It’s just a matter of time when those come, when those programs get canceled. It was supposed to be after Artemis three. Now it might be Artemis five, but the writing’s on the wall. That is not a sustainable program, and if we continue doing that, on my opinion, 10 years from now, when the Chinese are plugging in their nuclear reactor on the moon and looking over at our abandoned moon base because we couldn’t keep paying for those missions, it was unsustainable. That’s what’s going to happen if we continue on the same path.

We’re going to need to rely more on the private sector, more with fixed price contracting, in a way that NASA is not really comfortable with. We think deep space is sort of the traditional way we should be doing things. And I think NASA was more than happy to give Leo to the commercial space industry. But deep space was kind of a different deal. And they’re like, well, you know, Elon and commercial space, you guys can have Leo, but deep space is still ours. That’s not going to be true anymore. And it’s certainly not going…

David Ariosto – To, I mean, it certainly seems like the case in terms of what Elon is talking about, with regard to Mars, development of Starship, Peter Beck with in regard to even, you know, Venus mission, you know, I mean, this, this, this old mindset in which, you know, commercial mindset, that the commercial aspects focus on Leo and Earth’s orbits, where NASA is reserved for the bigger stuff. You said a lot of stuff in that, in that, that point. So before I wanted to get to the last question, if you’re taking the contrarian perspective. I gotta, I gotta push back a little bit in terms of that so, so let’s see how this goes.

So you said hard ish, right. I mean, I might, I can see that point in terms of moon landings, but this is the South Pole. This is Shackleton craters right near that lunar south when you have these 100 degrees of variable temperature swings. And you know, eternal darkness and constant light and and you know the importance of sort of the, if we’re talking about, you know, lunar resources in terms of water, they only exist in certain certain parts, right in those sort of permanently shadowed craters. So the counter argument to that is that if you establish a base, it needs to be established near some proximity to those, those cows, and in terms of the regolith that gets kicked up in terms of moon landings, you have to establish some sort of perimeter. So if you, if you do that, those perimeters can be quite wide, and it’s not outside the realm of possibility that those perimeters essentially take over the more valuable terrain on the moon.

And so if we’re talking about a perspective of flags and footprint footprints, I can see the point. But if we’re talking about sustained presence, much like what the Chinese are talking about, and to some extent now, what NASA is talking about in a sort of a greater way, I wonder if there is a primacy to being first here. And you know, the Cold War rhetoric has, has, there’s some damaging aspects to that, admittedly, right? Because there, it seems like, there has to be a sense of working together in some capacity. But I wonder, like, if a certain nation or certain company gets in a place first and is able to establish sort of a de facto claim of the region, whether that matters in terms of the ripple effects and the geopolitical concerns and the broader, you know, technological downstream effects that all of this has in sort of this new paradigm that we’re all looking at.

Phil McAlister – I think that would be true if, if they could effectively set up this perimeter that you’re talking about. I don’t believe that’s possible. The rim of the Shackleton Crater is about 40 miles long. That’s about the distance from DC to Baltimore. Is it possible to defend that entire line on the moon? I don’t think so. And even if we were first, do you think we would establish a keep out zone over the entire Shackleton Crater? No, the international community would not tolerate that, nor should it. So I don’t believe we should take over that entire crater.

I think just like you said, we can all cooperate. We can all, all have our space, even if we have property rights on the moon, which I think are inevitable and necessary for the moon to really…

David Ariosto – Become, which replies in the face of sort of the Arab Space Treaty at that point. So I mean, yes, we’re due for a bit of an update.

Phil McAlister – We are due for a bit of an update, absolutely, and we have been for a long time. So I really think that it’s, it’s inevitable that there are going to be multiple countries on the moon, and I don’t believe anybody’s going to be able to say this is our sole province of this huge area. It would be difficult to do that on the Earth, to defend that much territory outside of your own country. I just think it’s, I just don’t think it’s possible.

But you’re right. If that were possible, if they could set up a perimeter, and it would be de facto all of another countries, and they could say, “Don’t, you can’t come in,” then I do think that would have more serious geopolitical implications. I think what’s much more likely is for us to have some sort of cooperation on the moon, which I think will be a super positive development. Again…

David Ariosto – But it does involve property rights, because right, right now, we have these sort of de facto end claims in terms of what, what, what? You know, it’s almost akin to like having a slandered, like these mini embassies that might be reflective on the lunar surface, though. But one of the hallmarks of that ’67 treaty, the Outer Space Treaty, was that it had such widespread buy in. And we’ve seen subsequent treaties not have the teeth of that one.

And I wonder now, in this context in which you have kind of a bifurcated system, in which you have Artemis and you have all the nations that have signed on to that. But then you have, you know, the International Lunar Research Station as pushed by the Chinese and the Russians, and, you know, buy in from the Pakistanis. And so there’s almost like this cleaving now in terms of what the future of humanity might look like, in terms of which side is, is, is, you know, coming to bear. And that has real implications in terms of international law, in terms of, you know, just conflict avoidance and all, you know, like that. The nitty gritty of actually how you operate on orbit and in the cislunar space and the moon really matters when it comes to those types of things. I don’t know how you square that now, in terms of this competition,

Phil McAlister – Yeah, yeah, it’s very difficult to see how all that’s going to play out. It’s going to take a half a century for those norms and rules to really become established. And my crystal ball becomes kind of fuzzy after about one or two years out. I really can’t predict out 50 years, but I do know the things that we think are important here in the country: freedom, capitalism, I think, is at the core of what this nation is all about, competition and property rights.

I believe that is fundamental to us as a country, and I believe we are going to take those values with us into outer space. And we might encounter another political entity that has different rules, and we’re going to have to figure out how to get along or not, if something happens to one or two, one of them or not. I mean, that’s why you have to, just going to have to be flexible.

But I do agree that the way it’s shaping up right now, certainly with Artemis Accords and the lunar village concept, you have two very different ideas, but I think they’re totally coexistible, even as different as they are, as fundamentally incompatible. That’s fine. Look at all the different political systems we have here on Earth, innumerable, and we’re all getting along relatively peacefully, not, not to mention the big engagement that Russia’s taken into Ukraine. There’s always going to be some flare ups, I think.

David Ariosto – But, well, to your point, I mean, there’s, there’s a lot of precedent for this. A lot of precedent for, you know, Cold War adversaries working together, not only aboard the ISS, but even in the Arctic. You know, there’s, do certain operations between, between the Russians and the Americans that are still going on, that like just north of Svalbard, because the conditions are so harsh and so foreboding that, you know, it’s almost like those things kind of wither away, just for the, for the moment, and then come back in spades.

But, you know, I’ll ask you to bring that, break out the crystal ball once more, but not in terms of this broader geopolitical paradigm that we’re all kind of okay to navigate our ways through, but, but NASA especially. And when you look at NASA and the long term strategy that that agency has, and the emergence of the commercial sector, particularly in Leo, but really of all Earth orbits, do you, do you see NASA as being still that sort of anchor customer? It’s funny to even use the term customer in terms of the modern task, but I think that’s fair in terms of, you know, yes, the move from architect to client. Or is there, like, this scenario where NASA steps back in a really profound way, and focuses on things like James Webb and others, right?

Phil McAlister – So if you’d asked me that question two or three months ago, I would have had a much darker view of how we were going. It’s, you know, I had left the agency. I didn’t see any commercial space division anymore. Most of my colleagues that really knew about commercial space had moved on, and I didn’t see anybody in leadership at NASA that really embraced those, and the goals that I did, after Kathy Leaders left the agency. I didn’t see any really, anybody in senior management that even really knew what commercial space was all about, certainly not my boss, as much as I tried to teach him.

And so I had a pretty pessimistic view of things. You know, we had, when you look at the administrator here, this is a good example of what I’m trying to say. And we had Mike Griffin for a period of time. Then we had Charlie for a really long period of time. And then we had Jim Bridenstine. And I remember when Jim came in, younger person, had a kind of a new way of doing business. Certainly, he tweeted things, and it drove our PAO people crazy, because, you know, you weren’t just, had them on, actually, you had to clear everything through public affairs. And now he’s just tweeting out, “Oh my God.”

Well, he’s bringing new ideas, right, and new ways of doing business. And Jim was much more receptive to the commercial space industry at that time. I thought things were only going to get better and better and better, right. We would get fresh leadership willing to embrace commercial space more and more. And then, in a lot of ways, we went backwards with Bill Nelson. It was a very unusual choice in my mind. But that wasn’t even my father’s NASA, that was my grandfather’s NASA, the way he looked at the agency.

So the trend that I saw so clearly, going towards more commercialization, I felt like we had basically lost, lost time, three years of just, you know, really not moving in the direction that I felt like the agency should go in.

David Ariosto – And question, does the, does the agency then start to resemble, like, if you’re looking way out in the future, start to resemble this almost like FAA style overseer, yeah?

Phil McAlister – So that’s another, different, yeah. That’s a whole different question that I’ll get to in just a second.

David Ariosto – It’s all kind of baked into one in this, like, NASA is the only agency I’ve ever seen that people can go overseas and people have NASA T-shirts, and NASA has, like, no other government agency that has that. I wonder, like, is something, is, well, here’s the question maybe: is something lost, maybe, in terms of the push towards commercial, that when we achieve these great things in space—not to take anything away from all the amazing things that the commercial industry is doing—but that 1969 landing, that summer, was a, was humanity’s sort of collective moment.

And I cannot tell you how many people I’ve interviewed who were from different corners of the world that ended up gravitating and coming to the United States and working in the space industry precisely because they remembered that in their childhood, or had, you know, the downstream effects of it. But the point is that it was like this collective moment. And do you get the same, I don’t, I mean, I’m not presupposing an answer to this, but do you get the same thing in the commercial space when, you know, companies…

Phil McAlister – No, you don’t. No. You don’t. But that doesn’t mean that’s a bad thing. We had this epic moment with Apollo, and now things are different and things are going to change. I don’t think we should be trying to recreate Apollo and that unbelievably historic moment that we had. I think, again, the environment is different now. To recreate Apollo in some other fashion, I think, is not only impossible, but inappropriate, because we now do have, we can do, so much more with the commercial, with a commercial, a strong, vibrant commercial space industry in space, than we could without it.

Because without it, everything costs so much more. I mean, we could have hundreds of Starship launches for the five or six SLS launches and Orion launches, potentially, so we could be doing so much more. This is what I used to preach when I was at NASA. If we didn’t have the commercial space sector, our aspirations in space would always be limited by the NASA budget, that $25 billion plus or minus 2 billion, right. That would be the limiter of what we could do in space.

With the commercial space industry, it is not limitless, but it is certainly magnified multiple times when you look at all the investment from all the different companies that have come in for commercial space. So if you really want to explore space, if you really want, if you’re really a space nerd, really a space enthusiast, you can’t help but embrace the space industry, because it enables so much more exploration than we could possibly have done.

So yes, you might…

David Ariosto – Also Apollo. I mean, that was commanding, like, 4% of US GDP at that point.

Phil McAlister – We’re never going back there. That’s never going to happen, right. That was a one time in history kind of moment, and we’ve all, I think, agree…

David Ariosto – You think so. You think that will never happen. I mean, in terms of, like, you know, the growing development of the commercial sector and the increased primacy, and, you know, the sense that, you know, we’re moving more and more machines on orbit, and this, you know, conceivably could be sort of a new home in terms of where our data lives and AI processing. And, you know, the growth of this to the point where it’s not as, I don’t want to liken this to like the commercial air travel, because I think we’re a long ways away from that, but to the point where it becomes so important in terms of just the national story and the economics behind that, and the geopolitics that sort of wrap it all together. Is it, like, is that 4%, is, is that really just a one off?

Phil McAlister – Yes, in terms of federal expenditures, we can still have that future, baby. We can still have that future where we’ve got all this infrastructure and all these people living and working in space. It just doesn’t have to be paid for by the federal government. It pays for it in a different way, and through competition, capitalism and economic returns, and there will be, in my opinion, always a place for NASA to do those things that don’t have an economic potential, that don’t have an obvious return on investment, where you can’t get private capital because there’s just no return on investment.

So I believe, even with as strong a proponent as I am for commercial space, because I really do want to explore space. The moons of Jupiter sound super cool, Mars. I want to go to all these places, but we can’t do it with federal money only. We are going to have to do it a different way. And if you looked at my last LinkedIn article about the parallels to Mount Everest climbing, it’s the same sort of thing.

I mean, you know, when Sir Edmund Hillary climbed Mount Everest for the first time, it was epic, and it was extraordinarily expensive and extraordinarily labor intensive. When you look at it today, nobody cares, because people are going up all the time, but the number of people that scale Mount Everest is immeasurably higher now, because private industry came into the business of mountaineering and going up Mount Everest.

So if you want to keep the old paradigm, when only two people can reach the summit, and you’ve got hundreds of Sherpas and more, hundreds of porters all helping and these huge expeditionary kind of programs that cost hundreds and millions of dollars. You want to do that so two or 10 people can climb Mount Everest? Or would you rather have a different future where hundreds of people can go to Mount Everest? I want the alternate future that can only happen with a vibrant, successful, healthy commercial space industry. And I think NASA…

David Ariosto – Started that. I’m glad you mentioned federal dollars, because when you evaluate commercial partners, there is, like, there’s a question there, right? There’s a question of what’s truly commercial versus a contractor with sort of a different badge, right? Because a lot of these programs, SpaceX included, Blue Origin included, you know, they’re underpinned by federal taxpayer dollars. They’re routed a different way.

And certainly, the operations and sort of the sense of autonomy and, and growth within the industry itself is much more commercialized than it might have in the old, call it, cost plus valuation. But, you know, these companies don’t get as big as they are, they don’t do the big things that they’re planning on doing without federal taxpayer funding. And I wonder, in that constant and that construct, whether the Achilles heel of the American space program, which has always been the fickle nature of it. We, like, we orient towards one policy, and then a new administration comes in, we orient somewhere else. And we’re doing Mars, we’re doing the moon, we’re doing this.

And it just, you know, it’s all this sort of changing of priorities. And this is where it maybe goes back to that, that competition, and how that ultimately manifests in terms of what are we trying to achieve on orbit and deep space and all these other things. And so maybe the commercial sector insulates us a bit more. Maybe it doesn’t. I don’t know. What’s your sense…

Phil McAlister – Well, so I think you got to really be clear about what you’re saying and what you’re thinking about. Yes, all those commercial space industry, all those commercial space companies that you mentioned, do receive some number of federal dollars, but it’s not a subsidy. NASA is getting a return on all of that investment, and it’s multiple times the dollar, the benefit that we get from spending $1 in, as far as an anchor customer for the commercial space industry, versus $1 on a cost plus traditional contract. It is, it is immeasurably higher.

David Ariosto – Oh, yeah, no. I mean, I wasn’t questioning insulation from political wherewithal. That’s the question. Oh, I’m sorry, yeah. So still, there’s still a reliance on that then, like these are not companies that, that, that exist regardless. Now SpaceX probably would, but…

Phil McAlister – No, I made this case about 10 years ago that NASA is still the big kahuna when it comes to spending and one of the major customers. So where…

David Ariosto – NASA goes, that has some of the same old, like, pendulum swing problems, I would imagine. There certainly…

Phil McAlister – Will, until there becomes critical mass that enables the private sector to do it all by itself, which occurs and exists today in communication satellites. That market has been self sustaining without the government intervention or sub support for, you know, decades. We don’t really have any other market. Currently, I think it’s going to be public space travel, but we’re not quite there yet, obviously.

So I do think in this sort of transitory period, again, you can look back to my LinkedIn article about Mount Everest. There was this expeditionary period, and then there was this transition period where things started to change, but governments were still involved. They just weren’t the sole operator, architect and funder of all these, all these expeditions. And now you’ve got it where it’s commercial, it’s completely commercial, and the governments aren’t in there except for some regulatory function.

I think that’s what’s going to happen in space. And right now, we’re in this sort of transitory phase. I don’t know how long it’s going to last, but I do think it will require the commercial space sector and NASA working much more closely together. And so, and when I was about to say that, I would have had a different answer two months ago about where we’re going. Two things have really changed.

One, we have Jared Isaacman, an unbelievably forward-looking, probably the best person to be running the agency, willing and willing to embrace commercial space and willing to fight for it. He’s got a lot of energy, Jared, and I give them all the, wish them all the best. And Blue Origin flew New Glenn. And a lot of people were saying, “Oh, it’s just SpaceX, the commercial space industry. You can’t point to another, another one like that, certainly not like SpaceX.”

But now you got, it’s not just SpaceX, it’s Blue Origin, and it’s Rocket Lab that’s created this niche, and certainly is going to, seems to be ongoing concern. And then you’ve got all these other wannabes that are pretty close. One or two of those are going to make it through, and then we’re going to have this, the genie is not going back in the bottle. I kind of thought it was two or three years ago. I thought NASA was going to shove it back in the bottle, and we were going to do all this cost plus. And everybody forget about commercial crew and the way we were doing it.

But now I don’t think that, with the combination of Jared, with the combination of New Glenn, the combination of, of some of the other successes we’ve had in the commercial space industry, I think the genie’s out of the bottle. It’s an inevitable inevitability, and the large aerospace companies better get good at a different business model, because the old one isn’t going to work anymore. If they want to continue to be space explorers, they’re going to have to, they’re going to have to change and have a different way of doing business, because the old way is not coming back in any large form.

I do think, like I said, there will still always be some JWST missions, some unique things that don’t have a commercial or economic potential that only NASA could do. And we’re going to decide as a country we want to do those things. And so that might require a more traditional approach, maybe not completely like the old way, with some differences, but I do think there’s always going to be an emission like that, and it’s just the proportions are going to have to change.

David Ariosto – So, I mean, the way you describe it, I mean, almost makes me think of, sort of like, the early settlement of this country, in the sense that you had some of those early company towns, Virginia, Virginia Company, that was, you know, getting a loan from, from investors in England and, and kind of starting here, and you have these, like, company towns that spring up. You do have questions, though, in terms of, you know, transparency and democratic governance, and, you know, there’s, there’s other problems that can arise from that.

But, you know, I don’t know that there’s, there’s any utopia in terms of, in terms of any of this, but it’s a fascinating conversation. I really can’t thank you enough for joining us. Phil McAllister, NASA’s former longtime commercial space division chief and, and certainly has a few, few ideas. They can check them out on LinkedIn. So thanks so much for joining us. And it doesn’t sound like you’re blissfully retired at this point. That sounds like you got some kick left in you.

Phil McAlister – Yeah, I’m sticking around a little bit. I’m going to keep, I’m going to keep following NASA and the space program for, till the end of my days. It’s part of my DNA. You can’t be at a place 20 years without loving it. And I did love, I didn’t love every minute. But when I look back over my career 20 years, I really did love it there, and I still love NASA as much as I do believe it needs to change, and want it to change. That doesn’t mean I don’t love it. I’m just able to look at it and look at the way we can do things better. And that’s always been my outlook and my hope for, hope for the agency.

David Ariosto – Phil McAllister, thanks so much. Thanks again for joining.

About Space Minds

Space Minds is a new audio and video podcast from SpaceNews that focuses on the inspiring leaders, technologies and exciting opportunities in space.

The weekly podcast features compelling interviews with scientists, founders and experts who love to talk about space, covers the news that has enthusiasts daydreaming, and engages with listeners. Join David Ariosto, Mike Gruss and journalists from the SpaceNews team for new episodes every Thursday.

Watch a new episode every Thursday on SpaceNews.com and on our YouTube, Spotify and Apple channels.

Be the first to know when new episodes drop! Enter your email, and we’ll make sure you get exclusive access to each episode as soon as it goes live!

Space Minds Podcast

“*” indicates required fields

Note: By registering, you consent to receive communications from SpaceNews and our partners.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly