Now Reading: The space nuclear power bottleneck — and how to fix it

-

01

The space nuclear power bottleneck — and how to fix it

The space nuclear power bottleneck — and how to fix it

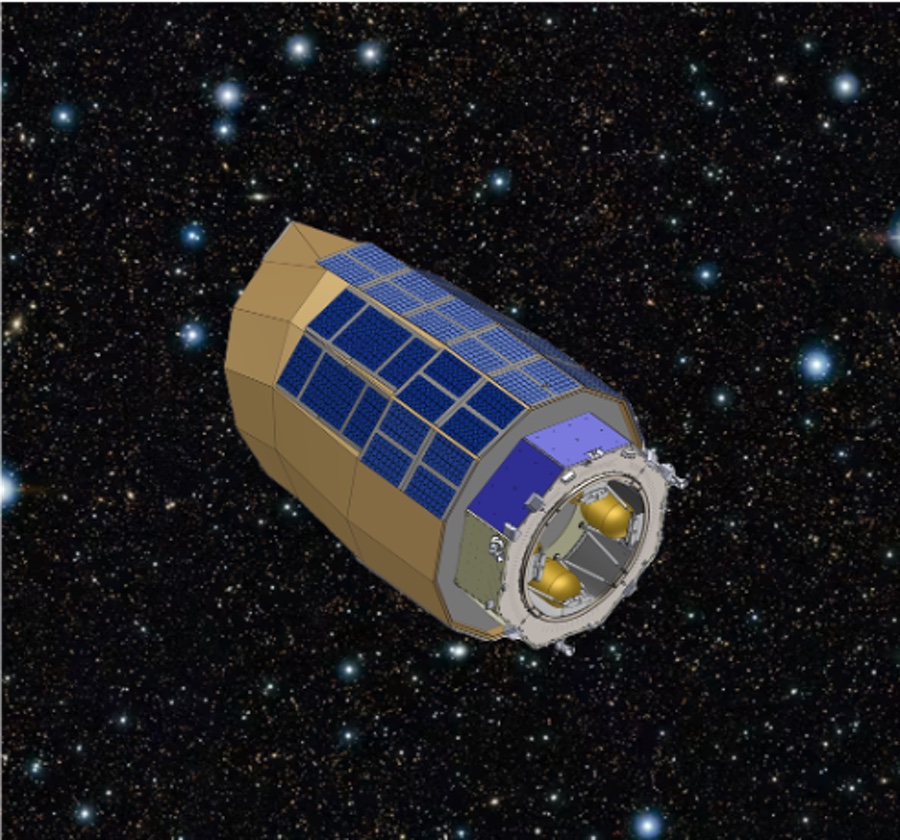

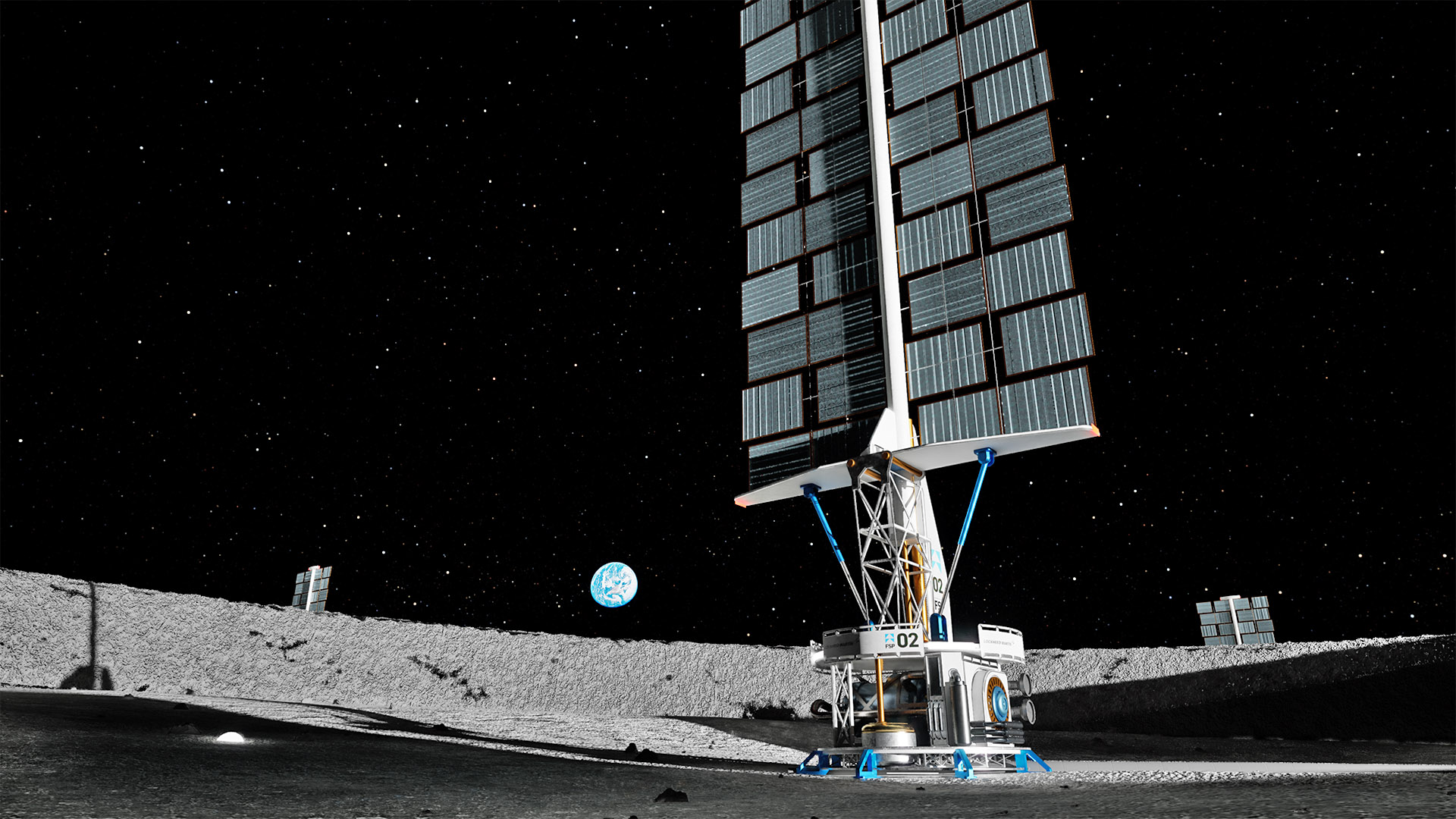

No technology holds more transformative potential for America’s space aspirations than nuclear power. Radioisotopes can safely produce heat that will enable deep space exploration and survival of the frigid lunar night while fission reactors are capable of producing kilowatts of electricity on the moon or in orbit. Fission is also the key to advanced nuclear propulsion systems that can expedite transit times to Mars and increase payload capacity throughout the solar system. Recognizing this, NASA has pledged to test a nuclear propulsion system by the end of 2028, and the White House has challenged the industry with landing a surface fission reactor on the moon in 2030. Ambitious goals, but absolutely within reach.

Contrary to common assumptions, reactor technology is no longer the bottleneck. The United States flew a reactor in space in the 1960s and has studied nuclear thermal propulsion for decades. Fuel is not the primary limitation either; the enriched uranium supply chain is modernizing quickly. Instead, today’s greatest barrier to nuclear power in space is infrastructure, not science. The U.S. currently lacks the testing, demonstration and integration facilities necessary to turn advanced reactor concepts into flight-ready systems.

Several fission system developers are preparing to compete for NASA’s Fission Surface Power opportunity. Many of these companies already have matured designs and in some cases prototype systems. But converting a paper reactor into mission hardware requires specialized testing environments that simply don’t exist today. These new facilities must support a range of fuel types — from High Assay Low Enriched Uranium to potentially even highly enriched uranium based on mission demand. They must be designed, licensed and constructed immediately if we expect to meet a 2030 lunar deployment.

Maturing and proving reactor performance is just the first step in releasing the clog of space nuclear system development. The next hurdle is system-level demonstration. Reactors do not operate in isolation; they integrate with landers, radiators, converters and deployment hardware. The U.S. lacks a nuclear compatible, vacuum-capable facility large enough to test a full fission-lander system. Such a facility must replicate thermal cycling, vibration, vacuum conditions and operational loads. It must blend space system engineering with the rigor associated with nuclear safety, essentially creating a new class of hybrid test complex. Without it, performance in space remains an assumption rather than validation. The result must be a very large facility that combines conventional space system requirements with nuclear and radiation safety requirements.

Added complexity is necessary to test nuclear propulsions systems. Nuclear electric propulsion systems will necessitate the equipment described above in addition to a test stand capable of thrust measurement and vector control under conditions that mimic the space environment. Nuclear thermal propulsion will require the same capabilities as electric propulsion, but with the additional hurdle of filtering an exhaust plume that has the potential to contain fission products. These systems cannot be responsibly deployed until they are tested in purpose-built facilities.

Even if testing and demonstration capacity existed, another major choke point emerges at the spaceport. There is no modern pathway to assemble and integrate a fission system onto a launch vehicle. Kennedy Space Center needs a dedicated high-bay, secure handling area, cranes, workforce pipelines and regulatory compliant procedure for enriched uranium systems. Attempting to squeeze nuclear payload operations into multipurpose spacecraft facilities would overlook radiological safety requirements and overload existing infrastructure, jeopardizing non-nuclear missions. A purpose-built integration facility is essential.

So how do we break through these barriers? First, the sense of urgency for nuclear systems in space has never been higher. Federal leadership recognizes the strategic importance of nuclear space power and has already increased funding while easing certain regulatory constraints. The financial and regulatory environment is unlikely to improve and the industrial base of reactor designers, landing platforms, radiators and fuel systems has reached a critical mass to support these missions. The window of opportunity is open, but it will not stay open indefinitely.

NASA should begin immediate site evaluations for new test and demonstration facilities, prioritizing locations that can leverage existing capabilities. Decommissioned or abandoned nuclear sites could dramatically reduce construction time by providing pre-qualified structures, radiological boundaries and environmental baselines. On the regulatory front, expanding the scope of NSPM-20 to include ground testing and operations of space nuclear systems would create a modern, risk-informed framework that will accelerate approval timelines without compromising safety.

In parallel, NASA must establish a dedicated nuclear payload integration facility at the Florida Space Coast. This is the final link in the chain where a tested, validated, full-stack system becomes a real mission payload. Without this capability, every nuclear mission stalls at the spaceport before it reaches the launch pad.

International competitors are not waiting. Nations with aggressive space ambitions are preparing to leapfrog the U.S. if we do not act with urgency. Space nuclear power will shape everything from lunar industry to Mars logistics to national security.

If America wants to lead, we must build, now. Build the test facilities. Build the demonstration complexes. Build the integration infrastructure. The technology is ready, the expertise exists and the moment is here. We only lack the physical foundation to unleash the systems already on the drawing board.

Delaying these investments doesn’t just risk missing deadlines — it risks ceding leadership at the dawn of a new era in space exploration. The bottleneck is ours to break and the future is ours to claim, but only if we act before someone else does.

David Schleeper is an aerospace engineer and space nuclear enthusiast.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion (at) spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. If you have something to submit, read some of our recent opinion articles and our submission guidelines to get a sense of what we’re looking for. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent their employers or professional affiliations.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly