Now Reading: The ultimate backup drive: the moon

-

01

The ultimate backup drive: the moon

The ultimate backup drive: the moon

In this week’s episode of Space Minds David Ariosto sits down with Chris Stott, Chair and CEO of Lonestar Data Holdings who explains how lunar storage could be humanity’s best defense against a digital catastrophe.

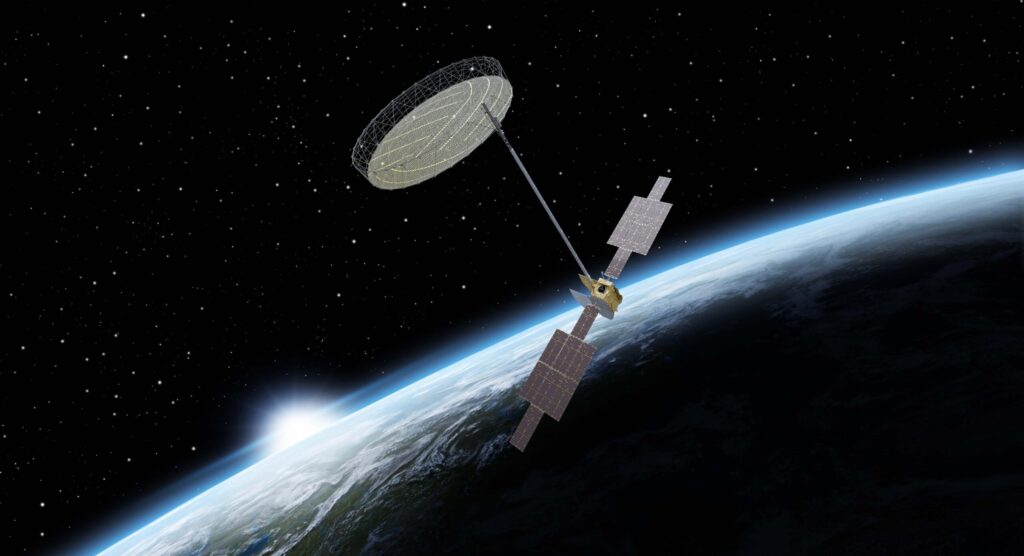

The discussions delves into the company’s efforts to establish data infrastructure beyond Earth, including the deployment of early-stage hardware and software in lunar orbit. Our conversation with Stott examines the challenges and implications of creating off-world data centers, and considers how such developments could serve both terrestrial markets and long-term space exploration goals.

Stott discusses the strategic and technical motivations behind the missions, including latency, security, and geopolitical competition—highlighting parallels with terrestrial data vulnerabilities and the growing scale of global data production. The episode also delves into the broader context of lunar development, the role of commercial space actors, and the evolving dynamics of global space policy.

And don’t miss our co-hosts’ Space Take on important stories.

Show notes and transcript

Click here for Notes and Transcript

Time Markers

00:00 – Episode Introduction

00:27 – Welcome Chris

01:27 – What is Lonestar

03:03 – On data storage

04:47 – Compute in space

06:55 – The moon for data storage

09:09 – On human usage

13:03 – Power Sources

17:01 – Geopolitical implications

19:05 – China

23:16 – The moon is key

26:20 – Space Takes – A furry of investments

Transcript – Chris Stott Conversation

David Ariosto – Chris Stott, it is good to see you again.

Chris Stott – You too, David, thank you for having me today.

David Ariosto – Yeah, it’s pleasure to have you. I think the last time I saw you was inside a surfers dive in Cocoa Beach in Florida. If I recall correctly, you were, you know, at that point, we were both there for the intuitive machines. I am one mission that was carrying a bunch of payloads, including yours, to the lunar surface. So it’s quite a bit has happened since then.

Chris Stott – Oh my goodness, yeah. Well, they’ve they fantastic cafe surfing Easter giving them a free plug. There amazing coffee in COVID beach. But you’re right. What a great place to meet and hang out and just be surrounded by a bunch of professional surfers and talk about surfing in space?

David Ariosto – Yeah. I mean, I think, I think that that mission, if I’m not mistaken, like you, had a software application that was loaded on the crap, sort of onboard computer that sort of hope to service, or the initial makings of a lunar data center, essentially. And so, you know, we’ve since had, I am two which, you know, I’ve seen you discussing quite a bit about, but I think maybe that’s where we can start. We can talk about that mission. But also, maybe more fundamentally, what, what we’re trying to do here in terms of Lonestar Data Holdings, which is your company there? Like, what problem are you trying to solve that’s not solved terrestrially or orbilly orbitally, in terms of sort of those, those data solutions.

Chris Stott – No would love to. So, David, it’s a real pleasure to talk to you. I mean, you’re an expert here too, so, I mean, that’s so please lead me, and let’s talk about, I am one, I am two. What’s happening in the industry? Why is all of a sudden, this becoming a thing in the industry too? What’s driving that? Let’s do that.

David Ariosto – So let’s get into IM 2. Let’s talk about item two, what was the payload there? What was accomplished?

Chris Stott – Oh, payload there was our first hardware and software. We tested all the way to the moon. We were switched on cislunar L1 39 orbits. We had storage on board for what, disaster recovery testing and storage on board for nine governments, including the State of Florida, we were testing a delay tolerant network for Vint Cerf. Press release coming out on that. We did a knowledge graph for Valkyrie intelligence, part of an LLM large language model, very fundamental part. We were running a risk five chip from micro Chem or microsemi SkyCorp built that for us. That payload, we had eight terabytes on board from Phison. Oh, my gosh. Oh. We had Starfield from Bethesda games. We were doing all things with, Imagine Dragons, we had commercial we had government, we were testing everything we need for these next stage admissions and everything worked for us.

David Ariosto – I think that that is a fundamental part. But I think the maybe the broader piece of this is actually what you’re doing here. Because when we talk about data processing and data storage and sort of the guts of what it takes to start to build sustainable either machine presence on the lunar surface or eventually human presence on the lunar surface, a core function of this is obviously data and you know what your company is doing, I think it’s so interesting in terms of creating this sort of, that cert in situ capacity that deals with, you know, some of the latency problems that you might have operating the moon otherwise, but just a whole host of other conditions that you have to contend with by putting data centers on the lunar surface, But not just the lunar service, the lunar south pole, which is just, I mean, it’s just a whole different ball of wax in terms of, in terms of the difficulty of operating there. So I wonder who we can maybe get into, into that aspect of it first, because just, just technically, what you have to achieve there in order to get these data centers is, is a tall order.

Chris Stott – Oh no. Well, thank you. And could we pick a harder place to go on the moon? I’m like, Really, guys, really. How about Far Side South Pole next time? I mean, oh my gosh, guys, come on. And so that was fascinating, because that’s where the intuitive machines were. Our ride to the moon under the NASA CLPS program were going. So we were kind of tagging along on that one. And we were fortunate, we have a we had a subcontractor who built the hardware for us, called skycorp. Then space built now. And, yeah, right. And, and there’s probably nothing that Dennis Wingo doesn’t know about the moon. So it was, it was ideal. They were the ideal partner for this. They flew an arm as radiation sensor inside, as an inboard hosted payload with us too to checking everything out.

Yeah, no, you’re right. Well, a couple of things there to unpack, right? First thing to unpack. When we look at all the all the technologies that are being put forward to go to the moon, we were always really confused. We see this great list from NASA, and we go, okay, that’s wonderful, yeah, robotic printing, Institute, resource utilization. And we’re like, where’s the it? Where’s the Information Technology guys? You need compute and data centers on the edge to run all of this. But it’s not listed anywhere. You put the word data in and that they’re not it’s, I think it maybe gets a mention, but it’s not data centers. It’s not data as we would talk about it. They talk about science data. It’s like we forgot to take the internet with us, and so that’s part, part of what we’re doing. But our main market is terrestrial, and we just look at Earth, Earth’s market there, and we look at the moon as earth’s largest satellite, and looking back. And so our next, actually, our next set of missions, we’re doing that beside us, head out to the Luna l1 so we actually get the sunlight 24 hours a day. We get a lot of benefits from that, and the distance and what we’re doing and terrestrial, but we’ll get into that later on. No, but you’re right. I mean, we need compute, and I love what Nokia were doing on this last mission with intuitive machines, yeah. And what the guys are doing outpost, we’re gonna, we’re going to be testing with them, because the idea that we make a brand new space radio to go to the moon, no, you just take your iPhone or your Android phone, right? And this idea that, well, of course, it works up there.

David Ariosto – Why? Depends on the supply chain issues. At the moment, I think it depends on, well that too.

Chris Stott – That’s true that I think the Indian space agency could come in and be brilliant with the new iPhones that are being made in India. That would be fantastic. But right, we’ve got to take that with us. Now. China has two data centers operational, one on the moon, on the Chang’e 4 mission, tiny, wee, wee little data center, and one in orbit around the moon on the Dutch radio astronomy satellite. They’re doing with them, Edge processing. Yeah, right, the same way we do a processing edge here on the ground. You do the same thing about that. There you be close to the action process and send the results. Huh? Sorry, I can go down rabbit holes. Actually have a key piece of carrot cake here at the office. And every time I go down a rabbit hole, they pull me a bit. Yeah.

David Ariosto – I think, I think we’re renaming the podcast space rabbit holes in the next chapter here, because that’s kind of like where we go here. But you mentioned so much, frankly, in the course of that answer, I almost part but, but I’ll start with the terrestrial application, right? Because I think it’s kind of interesting. It almost we you and I have talked about this before, but you almost made, sort of the comparison, the analogy to the so called seed vault in Svalbard, in terms of its potential application. But for those who don’t know, it’s it’s a, it’s a a vault, essentially buried beneath the ground in this archipelago just south of the North Pole that serves as, sort of almost like a backup for for the world’s agricultural crops. The moon, in your estimation, is sort of the ultimate backup center, in a way, or a backup locale. And I just, I’m curious if you can kind of unpack that for me explain why.

Chris Stott – Well, that the moon is so perfect for data storage. If it wasn’t there, we’d have to build it. I mean, it’s ideal the access to power, cooling, the orbital dynamics of this, the Lagrange points as our next step are absolutely superb for this. And why? Well, you said it yourself, the seed vault on Svalbard Island meant to protect all humanity’s greatest seeds for food for the next 1000 years.

Well, climate change, it melted and they had they were flooded and they almost lost everything. And so what we’re looking at is terrestrial data and backing it up premium to start with, the problems that we’re facing down here, where data has all of its value are extreme for everything from human error is the number one cause of data loss on a daily basis all the way through to nation state attacks on immutable data storage or ransomwares, you’ve got problems with cable fiber, not just what you read in the press about people chopping up cable fiber coming off Svalbard Island, right? It happens on the ground too. We’re finding taps on everything. People injecting malware into data centers. And data centers run our entire modern civilization. We’ve come so close, just on the cyber warfare a couple of times, of losing everything that runs our modern our modern civilization. So the idea is, it has value here, but let’s back it up somewhere else. Let’s just take it up. And as we’ve been doing that and talking about that, you’ve seen a lot of other things change on the ground with data creation. And if I may couple of firsts, I saved it for you. We actually checking this out, right? So when we started doing this, we saw the date by June 2023 the daily amount of data created by the human race in June 2023 was 2.5 quintillion bytes of information every day, more than yesterday.

David Ariosto – It’s hard to wrap your mind around it. Precisely how much that is.

Chris Stott – I had to look it up David and so. And that’s like 1000 petabytes. It’s an exabyte a day. So it’s a million MacBook Pros a day, with a terabyte in each every 24 hours. Now, the common wisdom. Thing was that that was going to double every two years. We just had a black swan event, or was it a trend? So here we are. We’re almost in June, 2023, 2025, sorry. So we were like, Oh, please, please, please, let it doubled. Please let us be right. And we were expecting five quintillion by today, and we just checked in the audience, please check, check yourselves anything. I tell you, you can Google or chat GPT, because it creates more data, which we have to back up. So we’re now running a 402, comptillion Bytes a day. That’s…

David Ariosto – And then, the concern then, though, is that the loss of that data and the sort of the loss of that knowledge base, or knowledge even, you know, potential for transfer is, is very real, in a way, I mean, and I think you’ve mentioned this in terms of, you know, precedence for this, in terms of antiquity, you know, Alexandria and the rest, yeah, I think that’s, that’s, that’s one of my favorite sort of analogies that that you’ve had.

Chris Stott – Oh, that largest data loss in human history that is so bad we still talk about it 2000 years later, it’s still taught in schools when Julius Caesar’s troops burnt down the Library of Alexandria and the Roman Civil War, right, right? Am I like going whoa, my gosh, imagine if that was today that has dozens happened. So we’re now at 402 quintillion bytes a day.

David Ariosto – I would I would push back in some sense, because data centers on the moon clearly are much more difficult in terms of physical tampering. But one would think that if you’re connected to the network in any capacity, you’re still very much vulnerable to cyber attack.

Chris Stott – Oh, absolutely no, David, you hit the nail on the head. Yes, absolutely. Which is why we’re very fortunate at Lone Star with the other things we’ve done in our careers, we actually have an itu filing the moon as a reference point of the world’s only commercial filing with 1000 megs of Ka, some expanded some s band, which actually gives us a completely, totally independent, isolated, global network. And we work with our data center partners on the ground. That’s interesting. So we actually don’t touch the broken networks on the ground. We don’t touch cable fiber. We don’t touch public switching networks, and isn’t it? Yeah, no, but you’re right. See, that’s the thing. We talk to people and say, Oh, I have a backup in Seattle. I have one in New York. And I’m like, it’s on the same network, right? Hackers get in and get into the network. They sit low and they see where all your backups are and take you down.

David Ariosto – Mars or Saturn, same network. Essentially, we’re talking about the same, same, same.

Chris Stott – But, well, latency is a good thing. Latency is a very good thing on storage. On storage, latency is amazing. Sure, you want latency, which is why this new data center region of space, it’s like going to a new part of the world, you know, say, I’m going to open a new data center region. What is the unique physical, physical attribute to this data center region? And what’s the laws? And if you treat space as a data center region, oh my goodness, look at this. And then you have the amazing work of star cloud of relativity. Now, having made their announcement with Eric Schmidt, and I think there’s a couple of others, I think axiom, there’s a couple of others out there doing this. Obviously, China’s doing it too. But this idea of move, of expanding, not replacing the Earth, but expanding compute into low earth orbit, yeah, where you’ve got free power, free cooling, but you’ve also got very low latency communications. It’s genius.

David Ariosto – I think Eric Schmidt has actually said explicitly, expressly, in a post, that that you know the play for relativity was specifically for for orbital data. Yeah. And then there’s the question of power sources too, in terms of, like, sort of that continuous solar power and other sources. But I want to get back to something that you said earlier, in terms of China, the term, in some ways, the driving geopolitical rationale behind a lot of this sort of, quote, unquote, next space race. And you know, whether or not it’s a spaces is contentious, depending on who you talk to, it’s a broader competition. Races may end, you know, sort of outside of that scope. I’ve often grappled myself with questions of the quote, unquote, lunar economy. And one of the, one of the interesting sort of retorts that I’ve heard has been, if China is there an economy, an economy will invariably exist with with, with the US, in the sense of the competition, geopolitically, bake into itself a degree of a degree of funding and and in that sense, sort of the nascent development of a market. Still space companies are overwhelmingly in terms of where the moon is centered, funded by taxpayers, and yet, with this geopolitical competition that has some hallmarks to the first space race with the Soviet Union, at least in terms of the drive, a lot of differences, obviously, particularly in the sense of the commercial. Sector. But I wonder, in the context of China having two data centers in and around the moon at this point, what that says to you in terms of, sort of long term plays, long term influence technical infrastructure, and then sort of the rules of the road that start to to emerge around this, this developing ecosphere.

Chris Stott – Oh, no, so much. To unpack that, David, that’s an excellent question. Excellent question is, are we in the middle or we are in the middle of a second Cold War, Cold War 2.0 and what does that mean? And the fact that and China only has two data centers on the moon, they have a patent for lunar data centers, global patent through the Shanghai Aerospace Engineering Institute. You can Google it, not you personally, but the audience Fascinating, right? They read the same books that we do. They read the same speculative fiction that we do. They see the same strategic advantage of the high ground that we do, and they see also what’s happening. I would suggest that while we sit there and debate the values of something and where should we do something, they just go do it and claim the high ground and claim the win, and that is massively upsetting.

Look, Chinese people love them. Their form of government, not so much, right? We’re in an end game. If I’m gonna put my swap the Lone Star hat and put the Institute of Space commerce hat, because we were looking at this a lot, we’re about to come out with something on this. We’re in an end game right now for humanity. We’re at a point where we either move from scarcity to abundance or stay in scarcity. We’ve got the energy and resources of space with space flight as a tool, just like fire is a tool, just like AI is a tool to lift our civilization, lift our nations, and lift the free nations of the world. Team freedom, right? We have this opportunity, but team tyranny does too. They have the same tools. They’re a little more monomaniacally focused. They know who, whoever controls geostationary orbit, controls the world. Whoever controls the moon controls geostationary orbit. It’s just physics and military strategy. If anyone tells you otherwise, put them in touch with me. I’ll have to start learning Chinese, because they’re gonna enjoy their time in the prison camp.

David Ariosto – I mean, at that point, yeah, well, I think, okay, maybe I might hear, you know, conversely is that, you know, the alternative side is more of this, this sort of consolidated, Uber elite, tech driven class of entrepreneurs that have captured policy making in a way that we haven’t seen before. And, you know, I want, I wonder it like is, is there a middle ground between these two stark realities here.

Chris Stott – Well, you know, I would say our greatest advantage, our only advantage right now, is our entrepreneurs, because we can move faster. That’s the only thing we can do, tapping into commercial markets to do something like I said, when we see the moon, we see earth’s largest satellite, we see fulfilling a terrestrial market, leveraging the physical properties and the orbits around them. But taking a cup, like I said, this is an end game situation. Alpha themahan, influence of sea power upon history, when you look at the influence of sea power upon history, but what about the influence of space power upon history? I’ve got a bottle of water right here. I’m getting so into this is a great question.

David Ariosto – Yeah.

Chris Stott – What I didn’t expect? So I’m riffing a little bit. So the influence of space power upon history. So Jerry Pournelle and Larry Niven wrote about this, as did Alfred Theo may have, the size of the Roman Empire was dictated by two weeks march from a body of water or from a Roman road. The size of the great Khans Empire was dictated by how fast and how well his pony riders could go. The size of the British Empire early on was and the Spanish Empire was dictated about how fast a ship could sail. How do you do command and control of the military, on of governance that then turned into steam, it turned into telegraph, it turned into radio. And here we are in the middle of this new Cold War where we have satellite communications, which actually, given the size of a government is determined by the size of the timing of speed of command and control. We can have a global governance, global governance. So what government? There’s a lot to unpack on that. There’s a lot to unpack, right? But the thing is, we see this. China sees this, yeah, and they’ve got a massive demographic problem. They’re down 400 million people in the next 25 years. The only people that can tell you is China’s century of the Chinese, right? I mean, so they have, they can, they don’t they? Today, they don’t have enough time, enough people to run their factories, run their military, or even live in their cities.

David Ariosto – Well, I think that it’s a really interesting point in the context that you know, one of the you know, arguably the advantages of the Chinese system, when it when it comes to space, is the continuity of strategic planning that being said. When you look at sort of the demographic questions that China’s facing, and perhaps long term questions about continuity of its own leadership, because it’s just it’s strikes me that there was almost like this tacit bargain that was struck, that was struck within China itself, in which groups would would deal with some of the more sort of draconian policies that came down from Beijing in exchange for an uplifting of quality of living, and once that sort of evens off a bit, these questions of sort of political want married with sort of the technical surveillance that is just being laid out in ways that we’ve never really seen before. I don’t know. I wonder if there’s a tension point there that that will eventually show cracks. Oh, in itself show show questions of continuity of those broader space policy initiatives that we’re talking about here.

Chris Stott – Oh, well, that’s interesting. David, exactly. They’ve got all of the demographics we just talked about problems there. We’ve got the problems of their surveillance state. They took black mirror as a guide. And, you know, 1984 from George Orwell, they saw that as a starter kit. But as we have seen in all of human history to date, the more a state crushes down on people. And at the same time, like with Lenin’s new economic policies that Stalin had to, like, really jump on top to stop the moment you bring economic liberalization into a command control economy dictatorship like China, the moment you do that, you start to create the pressure vessel that’s going to explode around you. We saw that explosion with Gorbachev and everything else. It took a long time coming, but interestingly spaced, SDI Strategic Defense Initiative with Jerry ponell, Larry Niven, Ronald Reagan, General Graham, all those guys, one of the key goals there was to bankrupt the Soviet Union. Stated goal.

Oh, lovely dome. We have coming up, don’t we? So isn’t it wonderful and that, but I look at this, and this is the thing, we’re free people. We’re chaos. Well, from the Institute of Space commerce, Larry and Jerry were there. Larry’s on Patreon right now. Jerry, may he rest in peace. Was our first page. And so this idea of the role of space and high technology in global view, the high ground protection and for now, access to resources and energy from space. Space, China’s doing space based solar power. We’re rapidly trying to do the same thing. This idea that space was this thing that people used to look at was the Apollo program and, oh gosh, maybe I have a satellite thing somewhere today. It’s intrinsic to everything we’re doing.

David Ariosto – Well, in that sense, is it really just a question of will and political wherewithal, or are there some so when I, when I look at the im two mission and some of the difficulties that that mission faced, and admittedly trying to land in the most difficult place that I think we’ve seen thus far. But you know, the idea of human rated landers landing there, and the idea of doing maintenance and dealing with hardware failures and lifecycle management, and, you know, trying to serve you, utilize lunar regolith for construction, Id printing and other materials, and how you bring things that, like all of these things, I don’t know that there’s a general understanding about how fundamentally hard that is and will be. And maybe it’s just a question of engineering, and we’ll all figure it out, and it just, you know, an obstacle that we just will hurdle. But I don’t know.

Chris Stott – How much, how much trouble I’m going to get myself in. I’ll probably find out, right? I love NASA. You know, my wife’s retired NASA astronaut. We have several astronauts on our board and advisory boards we have, and I, I am passionate about NASA and its mission and everything it represents, and everything it does, however look, and I know, I personally know very well, and they’re great friends to people who chose those landing sites, Minority Report coming in, saying, Guys, look, it’s there’s Probably the worst place to be. We’re finding water all over the moon.

The mid latitudes are easier for comms. We have shelter in the latitudes, so that removes all of these problems. And yes, there’s peak of eternal light. It’s been this talisman that people have had for years. And it was like, Oh, you’re doing the wilderness. I talk about going back to the moon like Moses. And then the promised land. We had the promised land. We had it. We had it in the Apollo program, right? I remember, remember in the Bible and Exodus, and God brings Moses to the promised land with the Israelites. And they go, it’s got Canaanites. We don’t want that. He’s like, right? You lot, 40 years in the desert, sort yourselves out, right? That’s what happened to us. We were at the promised land. We could have gone on to Mars. We could have all these energy, all this resources. We never we could have space based solar power. We never would have destroyed our environment. Yeah, and why? So now we’re finally back, and it’s like, guys, so what do we need? We need shelter. Well, there’s lava tubes. Incredible. Takes. Out of the radiation does all these great things for us. We kind of live in the moon. Oh, oh, that’s right. Arthur Clark, 2001 A Space Odyssey. All those guys were like, Yeah, that’s what we should do. And the next thing you know, we’re down at one of the hardest places. We’re finding water all over the moon, not saying the water isn’t important, but when you’re sending human beings, you can claim territory on the moon under the treaties and everything else, not sovereignty. I teach space law. Yeah, right. I think it’s great. But the things you can do that with unmanned and that’s what the that’s what the Chinese have been doing, yeah.

David Ariosto – Chris, I think we have, sorry, I can talk to you for the next 10, hours.

Chris Stott – Oh, no, I’d love to sorry. I mean, so tangents, right? No. So whoever wins the moon wins the earth wins energy and resource of scarcity to abundance. But also when you’re doing data backing up your data from space at higher orbits, like the l1 like the moon, and doing the compute and low Earth orbit that is the that’s the Holy Grail and star cloud and relativity and all the others doing this amazing. But that’s compute, low latency storage. Come see us. We do sovereign storage. We know how to do it. We’ve already done it. We’ve got all that ready to go, and that’s what we do. And looking forward to it too. David, thank you.

David Ariosto – Chris Stott, Lone Star, data holdings, it is always, always a pleasure talking with you. I never know where the conversations go from from the from biblical references to the Roman Empire to to to landing and putting data centers on the Moon is always a pleasure.

Chris Stott – Thank you, David.

About Space Minds

Space Minds is a new audio and video podcast from SpaceNews that focuses on the inspiring leaders, technologies and exciting opportunities in space.

The weekly podcast features compelling interviews with scientists, founders and experts who love to talk about space, covers the news that has enthusiasts daydreaming, and engages with listeners. Join David Ariosto, Mike Gruss and journalists from the SpaceNews team for new episodes every Thursday.

Watch a new episode every Thursday on SpaceNews.com and on our YouTube, Spotify and Apple channels.

Be the first to know when new episodes drop! Enter your email, and we’ll make sure you get exclusive access to each episode as soon as it goes live!

Space Minds Podcast

“*” indicates required fields

Note: By registering, you consent to receive communications from SpaceNews and our partners.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits