Now Reading: There’s liquid on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. But something’s missing and scientists are confused

-

01

There’s liquid on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. But something’s missing and scientists are confused

There’s liquid on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. But something’s missing and scientists are confused

Scientists have known for a while that Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, has rivers and seas of liquid methane on its surface. But it’s strangely lacking in deltas, a new study suggests.

On Earth, large rivers create deltas with sediment-filled wetlands. Deltas form when the mouth of a river empties into another body of water. Besides Earth, Titan is the only planetary body in our solar system with liquid flowing on the surface.

Researchers recently looked for deltas on the big Saturn satellite but came up empty.

“We take it for granted that if you have rivers and sediments, you get deltas,” study leader Sam Birch, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences at Brown University in Rhode Island, said in a statement.

“But Titan is weird. It’s a playground for studying processes we thought we understood,” he added.

Related: Titan: Facts about Saturn’s largest moon

The researchers were hoping to find deltas on Titan, because these landforms feature lots of sediment. The sediment in deltas tends to come from a large area, and deltas gather it in one place. Studying such sediment could reveal insights about Titan’s climate and tectonic histories — and perhaps even possible signs of alien life.

“It’s kind of disappointing as a geomorphologist, because deltas should preserve so much of Titan’s history,” Birch said.

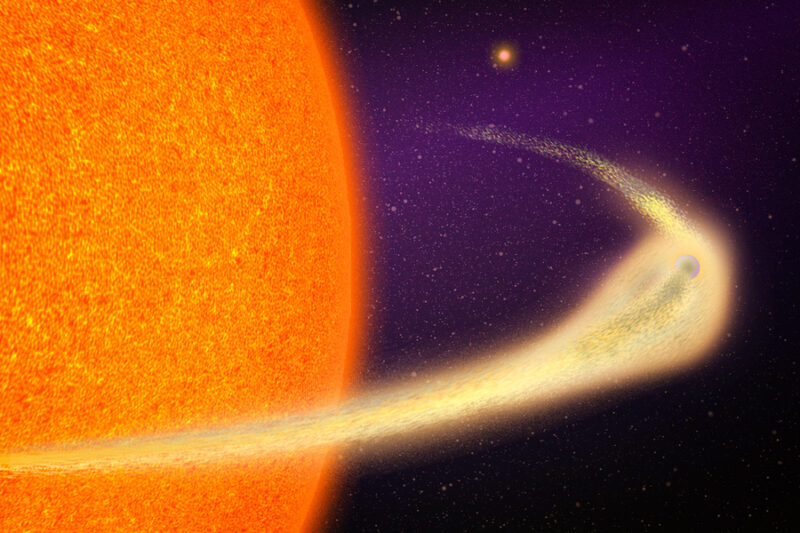

We know that Titan’s surface has flowing liquid methane, because NASA’s Cassini spacecraft spotted evidence of the stuff on multiple flybys. Cassini used synthetic aperture radar (SAR) to look through Titan’s thick atmosphere during these close encounters and found channels and large flat areas that are consistent with large bodies of liquid.

But shallow liquid methane is largely transparent in Cassini’s SAR data. Scientists have therefore had a hard time studying Titan’s coastal features, because it’s hard to make out where the coast ends and the sea floor starts.

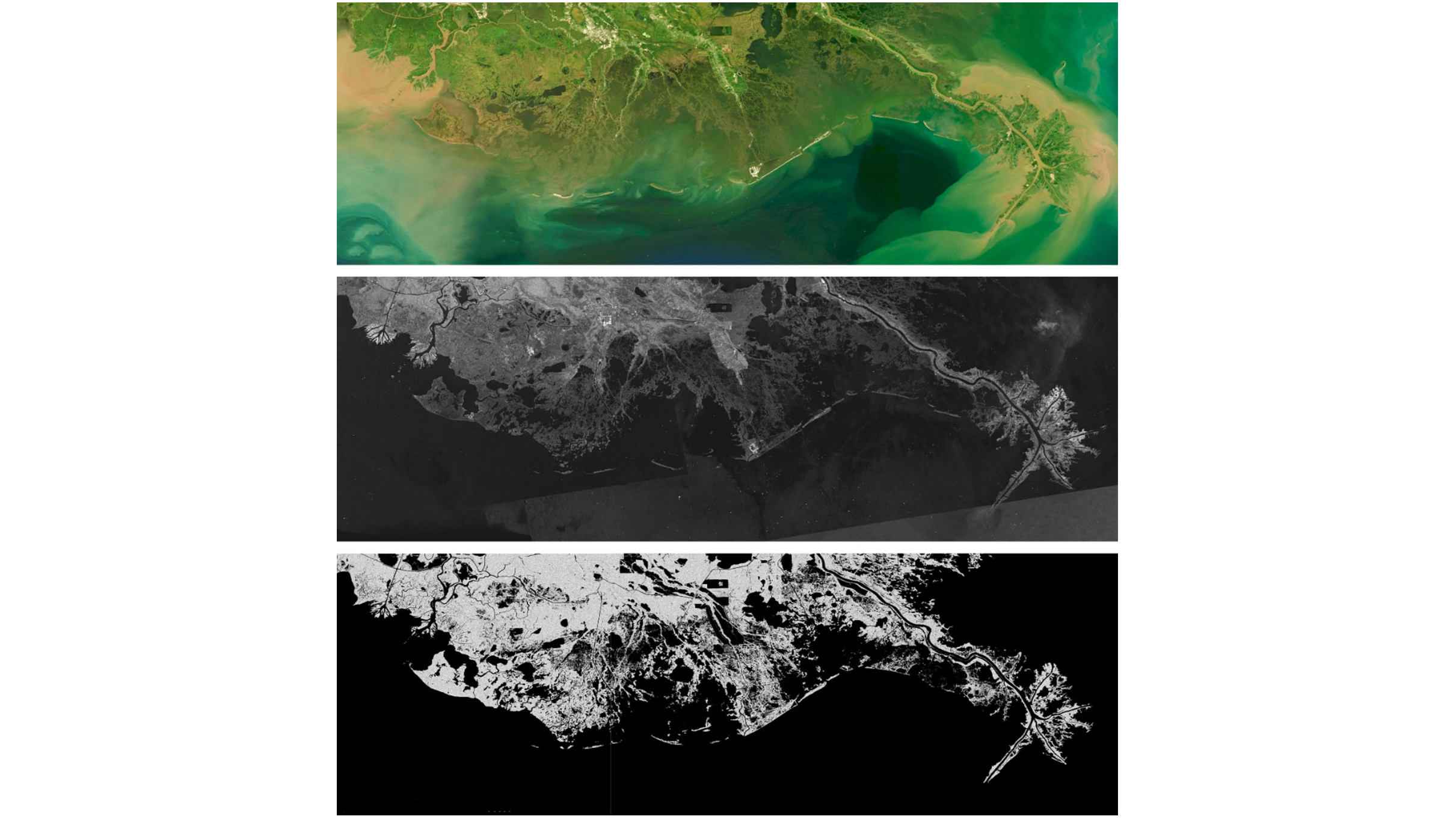

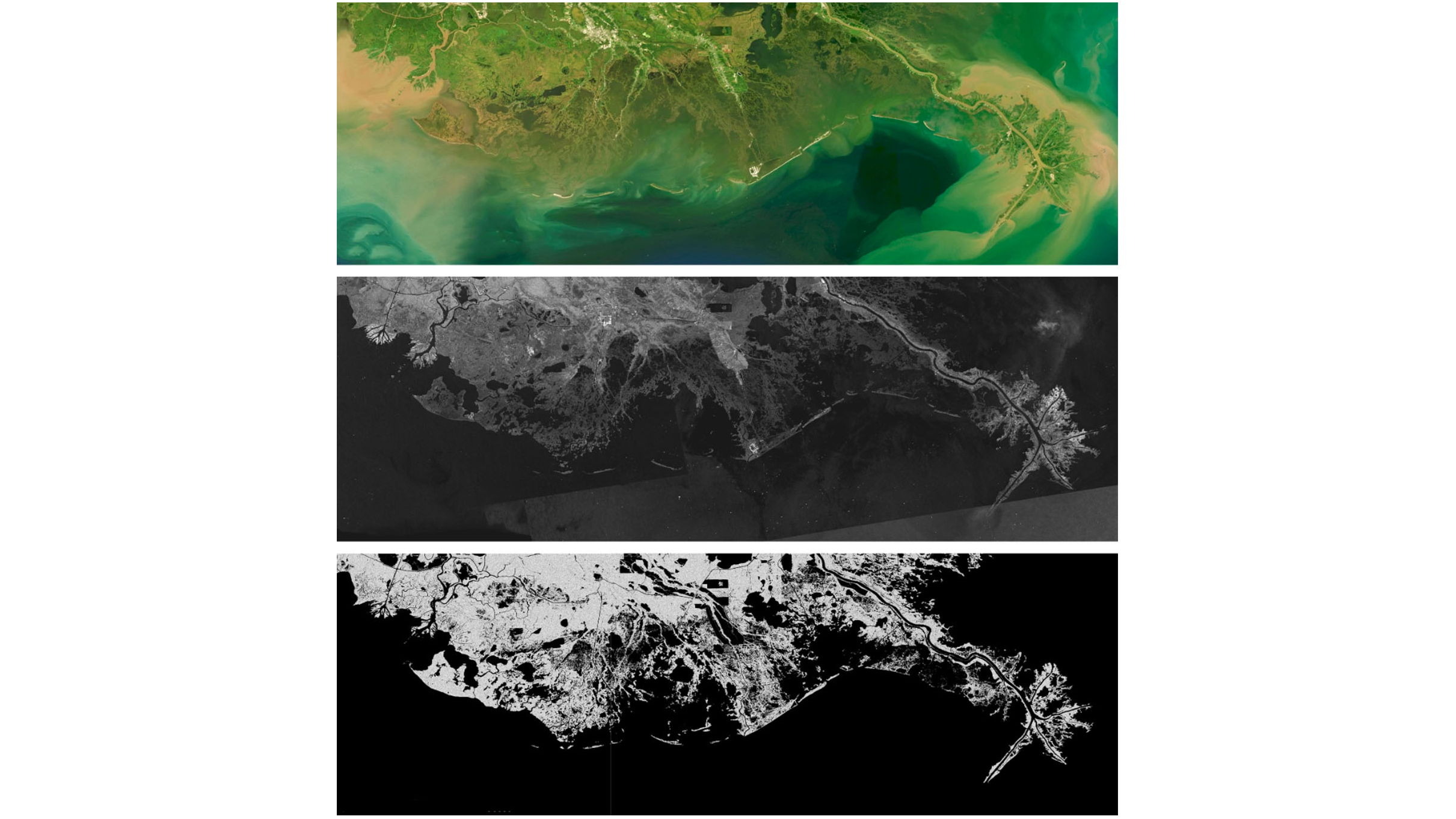

So, Birch’s team came up with a computer model that simulates what Cassini’s SAR would see when looking at Earth. But the model replaced the water in Earth’s rivers and oceans with Titan’s liquid methane.

“We basically made synthetic SAR images of Earth that assume properties of Titan’s liquid instead of Earth’s,” Birch said. “Once we see SAR images of a landscape we know very well, we can go back to Titan and understand a bit better what we’re looking at.”

Related stories:

The synthetic SAR images of Earth that they created “resolved large deltas and many other large coastal landscapes,” according to the researchers.

They say that new analysis of the Cassini SAR data also revealed other mysteries. For example, Titan’s coasts appear to have pits of unknown origin deep within lakes and seas, and deep channels cut across the moon’s sea floors offer no clue to how they got there.

“This is really not what we expected,” Birch said. “But Titan does this to us a lot. I think that’s what makes it such an engaging place to study.”

The new study was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets on March 25.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly