Now Reading: This moss survived in space for 9 months

-

01

This moss survived in space for 9 months

This moss survived in space for 9 months

EarthSky’s 2026 lunar calendar is available now. Get yours today! Makes a great gift.

- Space is a deadly environment, with no air, extreme temperature swings and harsh radiation. Could any life survive there?

- Reasearchers in Japan tested a type of moss called spreading earthmoss on the exterior of the International Space Station.

- The moss survived for nine months, and the spores were still able to reproduce when brought back to Earth.

Moss survived in space for 9 months

Can life exist in space? Not simply on other planets or moons, but in the cold, dark, airless void of space itself? Most organisms would perish almost immediately, to be sure. But researchers in Japan recently experimented with moss, with surprising results. They said on November 20, 2025, that more than 80% of their moss spores survived nine months on the outside of the International Space Station. Not only that, but when brought back to Earth, they were still capable of reproducing. Nature, it seems, is even tougher than we thought!

Amazingly, the results show that some primitive plants – not even just microorganisms – can survive long-term exposure to the extreme space environment.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed findings in the journal iScience on November 20, 2025.

A deadly environment for life

Space is a horrible place for life. The lack of air, radiation and extreme cold make it pretty much unsurvivable for life as we know it. As lead author Tomomichi Fujita at Hokkaido University in Japan stated:

Most living organisms, including humans, cannot survive even briefly in the vacuum of space. However, the moss spores retained their vitality after nine months of direct exposure. This provides striking evidence that the life that has evolved on Earth possesses, at the cellular level, intrinsic mechanisms to endure the conditions of space.

This #moss survived 9 months directly exposed to the vacuum space and could still reproduce after returning to Earth. ? ? spkl.io/63322AdFrpTomomichi Fujita & colleagues@cp-iscience.bsky.social

— Cell Press (@cellpress.bsky.social) 2025-11-24T16:00:02.992Z

What about moss?

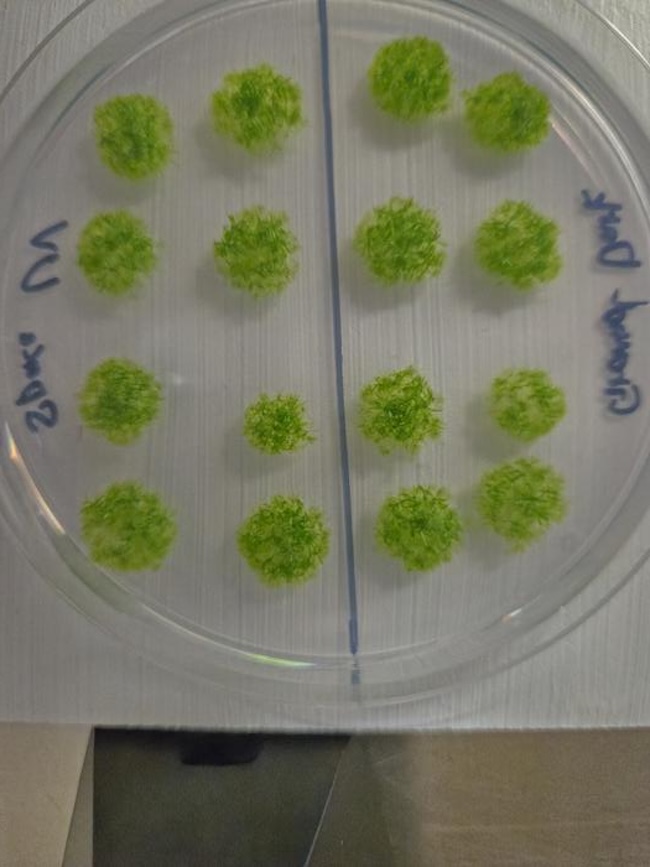

Researchers wanted to see if any Earthly life could survive in space’s deadly environment for the long term. To find out, they decided to do some experiments with a type of moss called spreading earthmoss, or Physcomitrium patens. The researchers sent hundreds of sporophytes – encapsulated moss spores – to the International Space Station in March 2022, aboard the Cygnus NG-17 spacecraft. They attached the sporophyte samples to the outside of the ISS, where they were exposed to the vacuum of space for 283 days.

By doing so, the samples were subjected to high levels of UV (ultraviolet) radiation and extreme swings of temperature. The samples later returned to Earth in January 2023.

The researchers tested three parts of the moss. These were the protonemata, or juvenile moss; brood cells, or specialized stem cells that emerge under stress conditions; and the sporophytes. Fujita said:

We anticipated that the combined stresses of space, including vacuum, cosmic radiation, extreme temperature fluctuations and microgravity, would cause far greater damage than any single stress alone.

The moss survived in space!

So, how did the moss do? The results were mixed, but overall showed that the moss survived in space. The radiation was the most difficult aspect of the space environment to withstand. The sporophytes were the most resilient. Incredibly, they were able to survive and germinate after being exposed to -196 degrees Celsius (-320 degrees Fahrenheit) for more than a week. At the other extreme, they also survived in 55 C (131 F) heat for a month.

Some brood cells survived as well, but the encased spores were about 1,000 times more tolerant to the UV radiation.

On the other hand, none of the juvenile moss survived the high UV levels or the extreme temperatures.

How did the spores survive?

So why did the encapsulated spores do so well? The researchers said the natural structure surrounding the spore itself helps to protect the spore. Essentially, it absorbs the UV radiation and surrounds the inner spore both physically and chemically to prevent damage.

As it turns out, this might be associated with the evolution of mosses. This is an adaptation that helped bryophytes – the group of plants to which mosses belong – to make the transition from aquatic to terrestrial plants 500 million years ago.

Overall, more than 80% of the spores survived the journey to space and then back to Earth. And only 11% were unable to germinate after being brought back to the lab on Earth. That’s impressive!

In addition, the researchers also tested the levels of chlorophyll in the spores. After the exposure to space, the spores still had normal amounts of chlorophyll, except for chlorophyll a specifically. In that case, there was a 20% reduction. Chlorophyll a is used in oxygenic photosynthesis. It absorbs the most energy from wavelengths of violet-blue and orange-red light.

Spores could have survived for 15 years

The time available for the experiment was limited to the several months. However, the researchers wondered if the moss spores could have survived even longer. And using mathematical models, they determined the spores would likely have continued to live in space for about 15 years, or 5,600 days, altogether. The researchers note this prediction is a rough estimate. More data would still be needed to make that assessment even more accurate.

So the results show just how resilient moss is, and perhaps some other kinds of life, too. Fujita said:

This study demonstrates the astonishing resilience of life that originated on Earth.

Ultimately, we hope this work opens a new frontier toward constructing ecosystems in extraterrestrial environments such as the moon and Mars. I hope that our moss research will serve as a starting point.

Bottom line: In an experiment on the outside of the International Space Station, a species of moss survived in space for nine months. And it could have lasted much longer.

Source: Extreme environmental tolerance and space survivability of the moss, Physcomitrium patens

Read more: This desert moss could grow on Mars, no greenhouse needed

Read more: Colorful life on exoplanets might be lurking in clouds

The post This moss survived in space for 9 months first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly