Now Reading: Twinkling star reveals the secrets of turbulent plasma in our cosmic neighborhood

-

01

Twinkling star reveals the secrets of turbulent plasma in our cosmic neighborhood

Twinkling star reveals the secrets of turbulent plasma in our cosmic neighborhood

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com’s Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Daniel Reardon is a Postdoctoral researcher at Swinburne University of Technology, studying pulsars and gravitational waves.

With the most powerful radio telescope in the southern hemisphere, we have observed a twinkling star and discovered an abundance of mysterious plasma structures in our cosmic neighborhood.

The plasma structures we see are variations in density or turbulence, akin to interstellar cyclones stirred up by energetic events in the galaxy. The study, published in Nature Astronomy, also describes the first measurements of plasma layers within an interstellar shock wave that surrounds a pulsar.

We now realize our local interstellar medium is filled with these structures and our findings also include a rare phenomenon that will challenge theories of pulsar shock waves.

What’s a pulsar and why does it have a shock wave?

Our observations honed in on the nearby fast-spinning pulsar, J0437-4715, which is 512 light-years away from Earth. A pulsar is a neutron star, a super-dense stellar remnant that produces beams of radio waves and an energetic “wind” of particles.

The pulsar and its wind move with supersonic speed through the interstellar medium – the stuff (gas, dust and plasma) between the stars. This creates a bow shock: a shock wave of heated gas that glows red.

The interstellar plasma is turbulent and scatters pulsar radio waves slightly away from a direct, straight line path. The scattered waves create a pattern of bright and dim patches that drifts over our radio telescopes as Earth, the pulsar and plasma all move through space.

From our vantage point, this causes the pulsar to twinkle, or “scintillate.” The effect is similar to how turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere makes stars twinkle in the night sky.

Pulsar scintillation gives us unique information about plasma structures that are too small and faint to be detected in any other way.

Twinkling little radio star

To the naked eye, the twinkling of a star might appear random. But for pulsars at least, there are hidden patterns.

With the right techniques, we can uncover ordered shapes from the interference pattern, called scintillation arcs. They detail the locations and velocities of compact structures in the interstellar plasma. Studying scintillation arcs is like performing a CT scan of the interstellar medium – each arc reveals a thin layer of plasma.

Usually, scintillation arc studies uncover just one, or at most a handful of these arcs, giving a view of only the most extreme (densest or most turbulent) plasma structures in our galaxy.

Our scintillation arc study broke new ground by unveiling an unprecedented 25 scintillation arcs, the most plasma structures observed for any pulsar to date.

The sensitivity of our study was only possible because of the close proximity of the pulsar (it’s our nearest millisecond pulsar neighbor) and the large collecting area of the MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa.

A Local Bubble surprise

Of the 25 scintillation arcs we found, 21 revealed structures in the interstellar medium. This was surprising because the pulsar – like our own solar system – is located in a relatively quiet region of our galaxy called the Local Bubble.

About 14 million years ago, this part of our galaxy was lit up by stellar explosions that swept up material in the interstellar medium and inflated a hot void. Today, this bubble is still expanding and now extends up to 1,000 light-years from us.

Our new scintillation arc discoveries reveal that the Local Bubble is not as empty as previously thought. It is filled with compact plasma structures that could only be sustained if the bubble has cooled, at least in some areas, from millions of degrees down to a mild 18,000 degrees Fahrenheit (10,000 degrees Celsius).

Shock discoveries

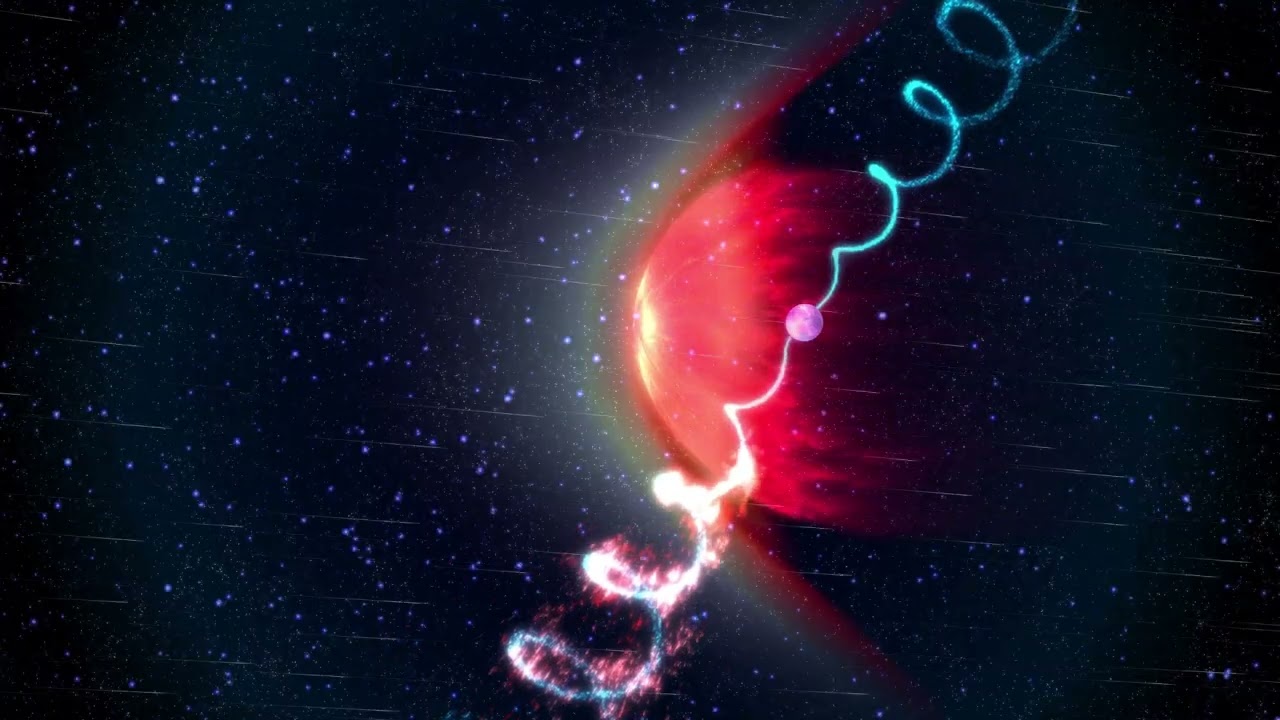

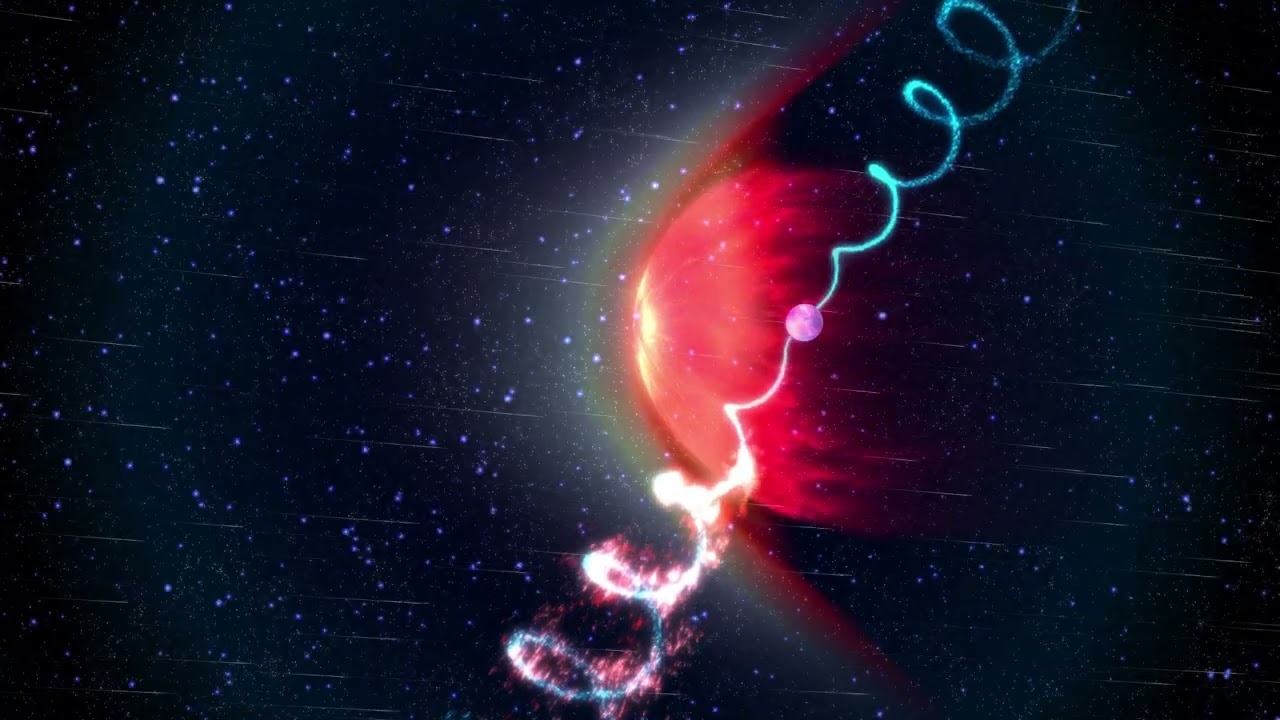

As the animation below shows, the pulsar is surrounded by its bow shock, which glows red with light from energized hydrogen atoms.

While most pulsars are thought to produce bow shocks, only a handful have ever been observed because they are faint objects. Until now, none had been studied using scintillation.

We traced the remaining four scintillation arcs to plasma structures inside the pulsar bow shock, marking the first time astronomers have peered inside one of these shock waves.

This gave us a CT-like view of the different layers of plasma. Using these arcs together with an optical image we constructed a new three-dimensional model of the shock, which appears to be tilted slightly away from us because of the motion of the pulsar through space.

The scintillation arcs also gave us the velocities of the plasma layers. Far from being as expected, we discovered that one inner plasma structure is moving towards the shock front against the flow of the shocked material in the opposite direction.

While such back flows can appear in simulations, they are rare. This finding will drive new models for this bow shock.

Scintillating science

With new and more sensitive radio telescopes being built around the world, we can expect to see scintillation from more pulsar bow shocks and other events in the interstellar medium.

This will uncover more about the energetic processes in our galaxy that create these otherwise invisible plasma structures.

The scintillation of this pulsar neighbor revealed unexpected plasma structures inside our Local Bubble and allowed us to map and measure the speed of plasma within a bow shock. It’s amazing what a twinkling little star can do.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly