Now Reading: We led NASA’s human exploration program. Here’s what Artemis needs next.

-

01

We led NASA’s human exploration program. Here’s what Artemis needs next.

We led NASA’s human exploration program. Here’s what Artemis needs next.

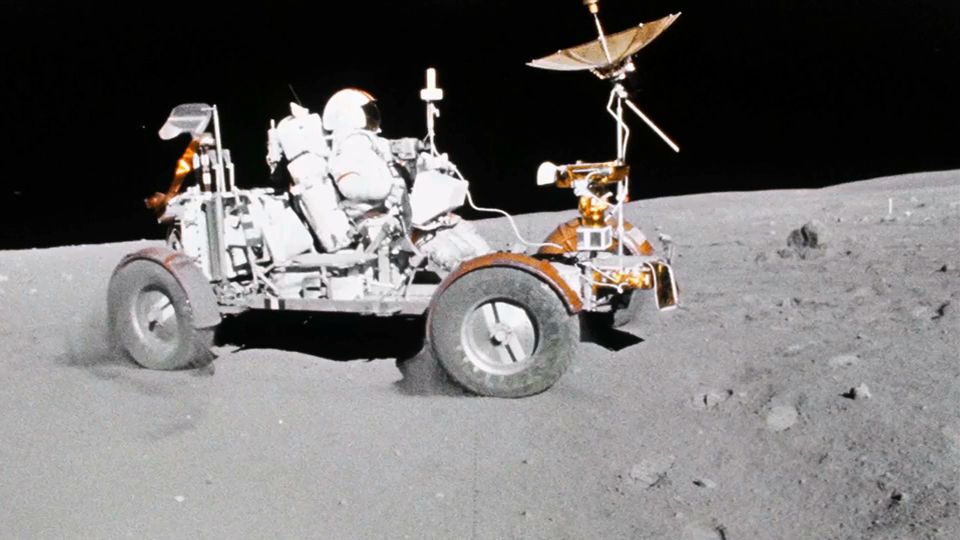

The recent passing of retired Navy Capt. Jim Lovell, an astronaut and one of our great American heroes, propelled many of us back to the iconic scenes from the superb retelling of the Apollo 13 movie in 1995. The three of us lived through that fateful mission in 1970, as the astronauts and mission control team dealt with critical issue after critical issue with the crippled Apollo command module and watched as Tom Hank’s line, “We just lost the moon,” became true.

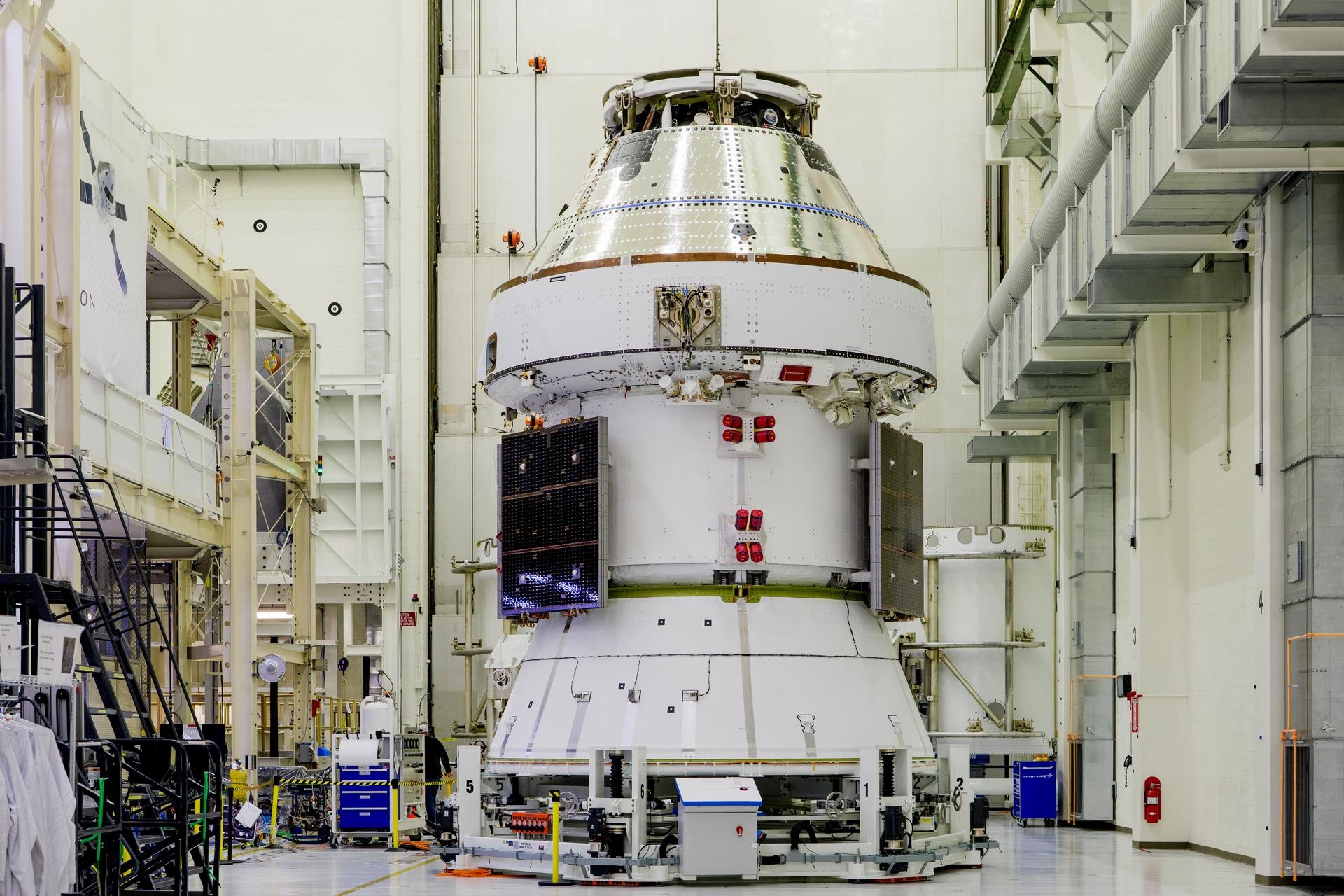

Metaphorically, we as a nation now stand at that same moment. Over the past decade, as critical delay after critical delay has slowed NASA’s Artemis schedule – first from the Space Launch System, then the Orion capsule and most recently, irrespective of Flight 10’s success, the Starship lander – it has become clear that we are once again about to lose the moon. This time though it’s not about a single mission; it’s about America’s leadership in space.

All three of us have at one time in our careers been in charge of NASA’s Human Exploration program and we have had the privilege over a combined century of leading some of the nation’s most important and most complex space programs in the DoD, the National Reconnaissance Office and at NASA. To us, it is indisputably clear that the plan for Artemis will not get the United States back to the moon before China.

It’s important upfront to appreciate that none of us are saying this because we don’t believe in the critical role that commercial space companies are playing and will continue to play in our future. None of us are beholden to any large space firm. Each of us has in fact worked tirelessly to help new space firms become part of the larger government space ecosystem. We believe that continued U.S. leadership in space will rely on the likes of SpaceX, Blue Origin and many others over the coming decades as we open those new space frontiers.

All three of us support President Trump’s vision that we must reform NASA and move off the old, expensive ways of doing business to truly embrace the entrepreneurial space zeal that has made space “cool” again. But all that enthusiasm cannot change the cold hard facts that the current program is in trouble, that the mission date for Artemis III has been pushed back year after year since it began and that the success of a single Starship flight does little to assure a lander will be ready within the next five years. In fact, the number of technical hurdles SpaceX has thus far overcome pales in number and complexity to those that lay ahead.

While SpaceX has proven time and again to be able to conquer tough technical issues, it’s the scale and number of challenges still to go that make this time different. As an example, in NASA’s original contract selection statement, NASA identified a “significant weakness” in SpaceX’s technical approach “due to SpaceX’s complicated concept of operations. SpaceX’s mission depends upon an operations approach of unprecedented pace, scale, and synchronized movement.”

The “unprecedented scale” at that time reflected the need for SpaceX to do between six and 10 never-before-attempted in-space cryogenic refuelings in a compressed and uncertain time frame. As with many technical challenges that have never been attempted, the problems get harder, not easier the more you learn. Today, NASA estimates that the operation will require somewhere between 15 and 20 refuelings plus the development and prepositioning of a fuel depot intermediary in space. We do not know the exact time period for those launches because neither NASA nor SpaceX has told us. But this pace of operations would be nothing less than historic and appears to represent a faster operational tempo than even Falcon 9, a far smaller and far simpler rocket, has managed to achieve after a decade of flying. Even when all that work is done, it still remains unproven that the now-fueled vehicle can be human rated, can land safely on the moon and can return our American astronauts safely to Orion for the trip back to Earth.

We have nothing but respect for SpaceX’s engineering prowess and none of us doubt that all of this will eventually happen. But our scars tell us it won’t happen quickly, and certainly not on a schedule that keeps the U.S. in the lead. It’s notable to recall that when SpaceX was first awarded their contract, they claimed that they would be able to do it all by 2024 – yet today as we approach 2026, we are still unable to fly repeatedly with high confidence much less accomplish those far harder goals. Our intent here is not to impugn NASA or SpaceX’s efforts; and this is not a call for Congress to give NASA more money. Rather, this is intended as wakeup call for us all.

The Chinese have outlined a bold vision for a lunar base and for an eventual mission to Mars all predicated upon their first manned lunar mission in 2030. Based on their proven and almost unbroken record of successes in achieving their space milestones as planned, we take them at their word. Meanwhile, Congress and the president have made it clear that they expect our nation’s space leaders to get there first. The president understands that such goals are not merely about interplanetary exploration. Achieving these goals is about assuring American leadership both on and above the surface of the Earth.

The space race of the last century cemented U.S. technological leadership for over 70 years and led to the scientific and industrial supremacy that defeated Communism and laid the foundation for sustained American economic advantage. We don’t have a crystal ball, and we can’t say for sure that the winner of this 21st century space race will get to wield that kind of economic lordship over the anticipated multi-trillion-dollar annual space economy. But we don’t want to find out by losing.

So, what can be done? First and foremost, we need ground truth – someone to “check our homework.” NASA’s Artemis program lacks any true mechanism of public scrutiny needed to verify its status, especially for its landers. So, while to us the predicament is crystal clear – that alone can’t be the basis for the bold action that will be required if we are right. NASA needs to stand up a truly independent review team immediately to provide an assessment to the acting administrator, the president, and Congress within the next 45 days because, if a “Plan B” is needed, that planning needs to start now.

If we are right, then the hard work begins. Right now, we need transparency to confirm for the nation what we think we already know. The stakes could not be higher and we refuse to allow our nation, in this current century, to “lose the moon.”

Doug Loverro is the former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy and former Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations at NASA. Doug Cooke is former NASA Associate Administrator for the Exploration Systems Mission Directorate with a NASA career of 38 years at Johnson Space Center and NASA Headquarters. Dan Dumbacher is the former CEO of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, a professor of engineering practice at the Purdue University School of Aeronautics and Astronautics and a former Deputy Associate Administrator for Exploration Systems in Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

Previous Post

Next Post

-

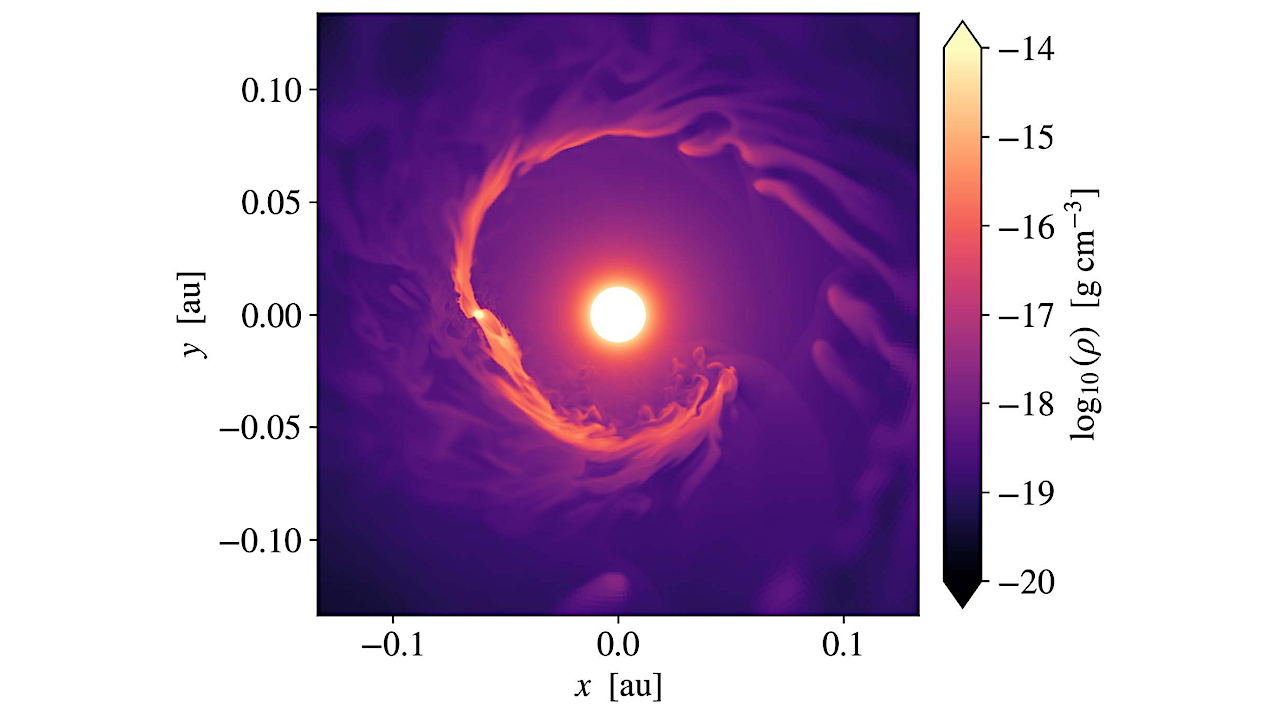

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors