Now Reading: We need a ‘Planetary Neural Network’ for AI-enabled space infrastructure protection

-

01

We need a ‘Planetary Neural Network’ for AI-enabled space infrastructure protection

We need a ‘Planetary Neural Network’ for AI-enabled space infrastructure protection

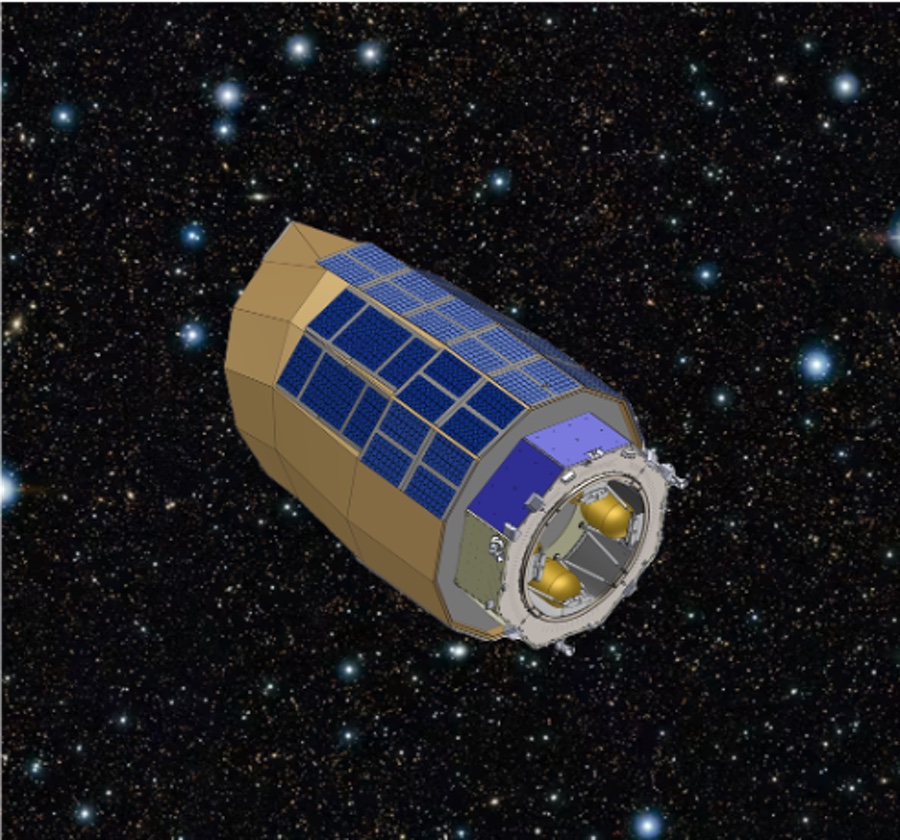

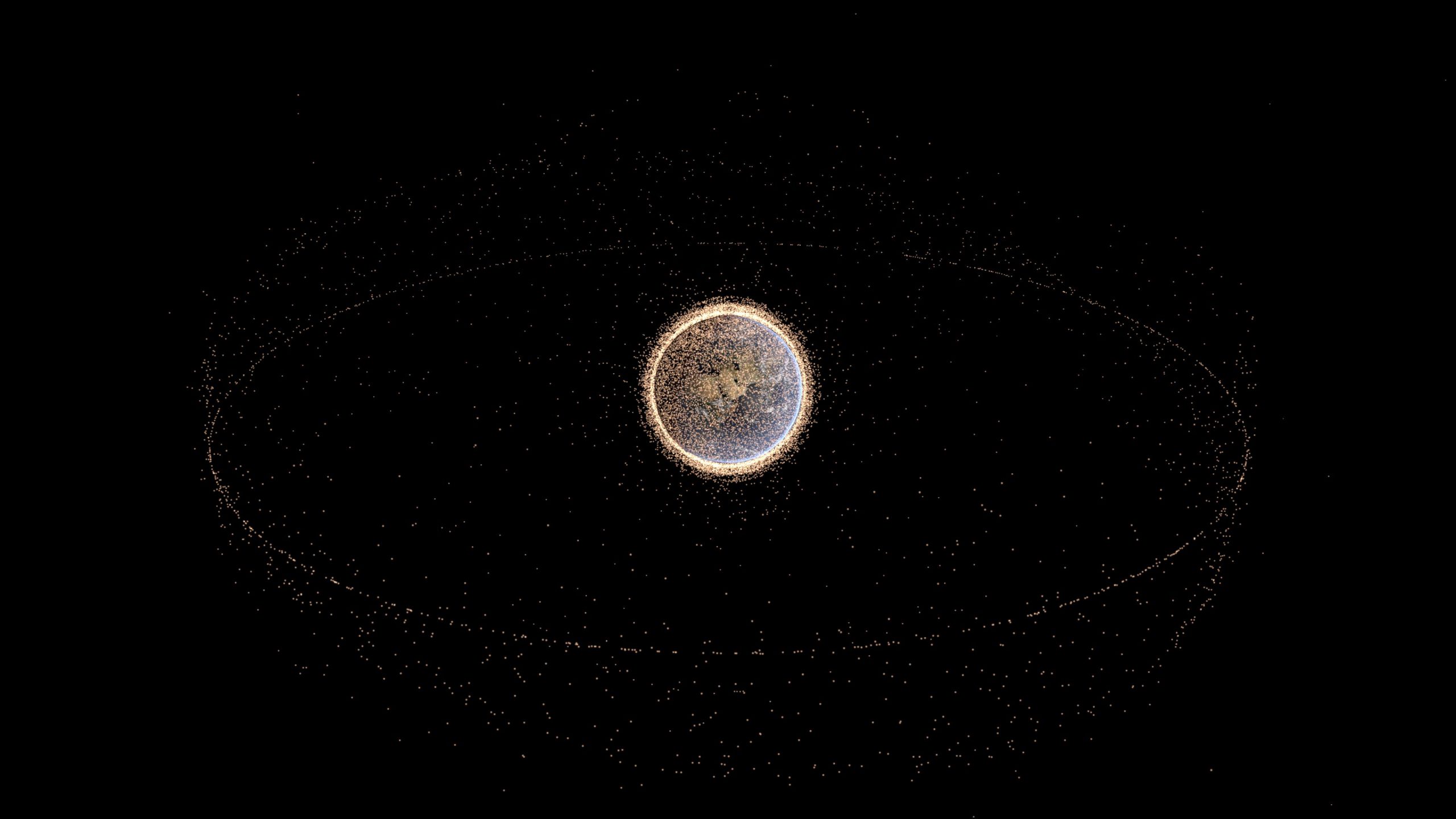

You may not see it with the naked eye, but in Earth’s orbit, a silent crisis is unfolding. With over 11,000 active satellites currently in orbit — a number expected to reach between 30,000 and 60,000 by 2030 — 40,500 tracked objects of 10 cm and more, 1.1 million pieces of space debris between 1 and 10 centimeters, 130 million pieces of space debris between 1 millimeter and 1 centimeter, our orbital infrastructure faces unprecedented challenges. Traditional space monitoring systems that were designed for a much simpler era of space operations are struggling to keep pace with this exponential growth in orbital activity and space debris accumulation.

And the stakes are high: even a single collision between two satellites or between a satellite and debris of 1 centimeter or more could trigger a cascade of additional debris, potentially rendering entire orbits unusable for decades as predicted by Kessler syndrome. The threats extend beyond mere collision risks. From sophisticated signal interference to potential adversarial actions, the security challenges facing our space assets have evolved dramatically.

As commercial launches accelerate, micro-satellites become cheap and mega-constellations become reality, the mathematical complexity of tracking and protecting our space assets has outgrown human analytical capabilities. If we are to manage the hazards in orbit, we must be building better space situational awareness (SSA), anomaly detection, and predictability in orbit. The inherent complexity and the need to respond to threats and issues faster is calling for, among other things, AI assistance. In my view, the world needs a Planetary Neural Network (PNN) — a system capable of managing these challenges for operators around the world.

AI in the space security framework

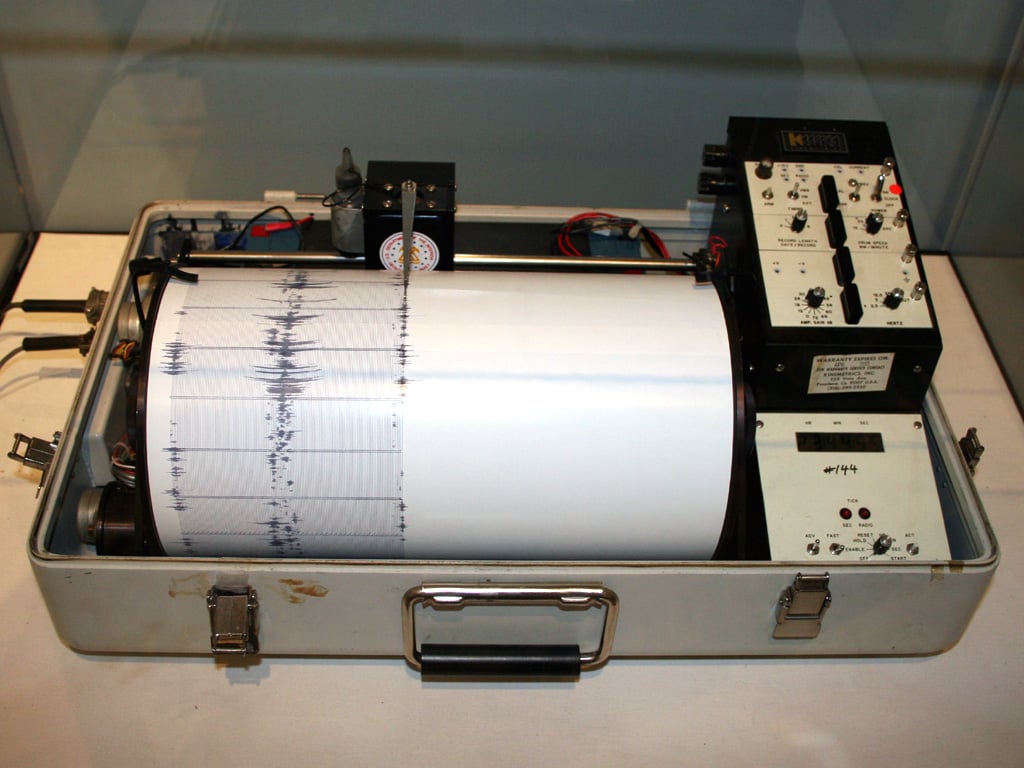

Optical and radar ground systems detect orbital objects by transmitting electromagnetic waves and analyzing the echoes reflected back from those objects. While traditional radar signal processing methods have proven robust, they reach their physical and algorithmic limits when dealing with weak radar cross-sections, cluttered signals or transient detections. As a result, smaller debris often goes undetected, leading to incomplete orbital catalogs and increased collision risks.

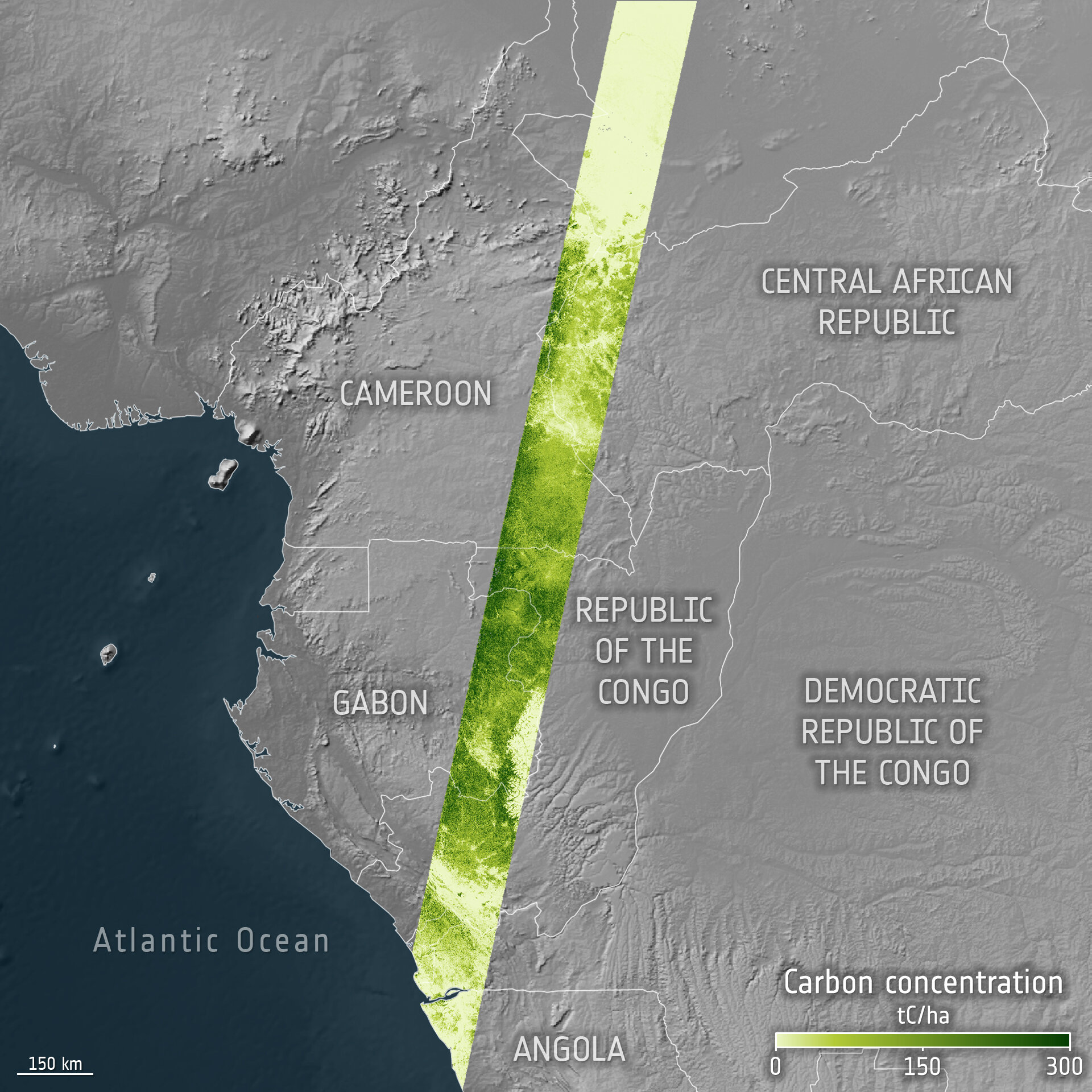

Recent advances in machine learning and deep learning have opened new possibilities for processing complex radar and optical data. By introducing AI-based layers into the signal processing chain, systems can enhance the detection of weak signals, filtering out noise and atmospheric interference. AI can identify and classify orbital objects, recognizing patterns that correspond to shape, spin state or orbital regime, and can predict trajectories and potential collisions with greater accuracy, even when observational data is incomplete or uncertain.

This integration marks a paradigm shift from purely physics-based models toward data-driven intelligence, capable of adapting to dynamic observation conditions in real time as well as detecting, confirming and classifying smaller pieces of debris.

For example, a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) trained on thousands of radar echoes can recognize the unique spatial signature of a small metallic fragment, even when its signal is partially masked by noise. This greatly improves the sensitivity and reliability of detection networks such as those operated by emerging SSA providers.

While CNNs excel at spatial analysis, they do not account for temporal evolution, an essential aspect of object tracking and orbit prediction. To address this limitation, researchers combine CNNs with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. These recurrent neural networks are capable of learning long-term dependencies in sequential data, making them ideal for analyzing how an object’s radar or optical signature evolves over time.

AI capabilities allow for continuous tracking, even when data is intermittent due to sensor gaps or poor observation conditions. The system can also disambiguate overlapping trajectories and maintain object identity across multiple sensor networks.

The Planetary Neural Network (PNN)

To transform the way orbital debris is tracked, cataloged and managed, I propose a “central nervous system” for orbital awareness. This system would integrate multiple data streams — from satellite telemetry, ground-based sensors and electromagnetic spectrum analysis to social media reports, something typically far outside the realm of space engineering. All contributing to a dynamic, real-time picture of the space environment and SSA.

The PNN sounds elegant. But turning it into reality would be anything but easy. The road to full-scale adoption remains lined with formidable technical and operational hurdles.

One of the most persistent challenges is the lack of data interoperability. Satellite operators both public and private use different formats, sampling rates and labeling conventions. For precise orbit tracking, global synchronization must reach millisecond accuracy that is hard enough on Earth and even harder across orbital nodes.

For AI, that’s like trying to assemble a puzzle where each piece was cut by a different manufacturer. The result is fragmented data pipelines that slow down learning and make it harder to deploy models at scale.

To make the PNN viable, interoperability must occur at three levels:

- Data format standardization: All observations must be converted into a shared, machine-readable schema, such as CCSDS (Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems) standards.

- Coordinate and time unification: Interoperability is impossible without a common spatio-temporal reference.

- Semantic and metadata harmonization: Even with the same formats, sensors use different terminologies and measurement units.

Another technical barrier with AI use is the false positive generation. A false positive occurs when a system detects an object that isn’t there, a random fluctuation, an interference pattern or a misinterpreted signal. For radar and optical tracking, these phantom detections are surprisingly common. They can come from: thermal or electronic noise that mimics a weak radar echo, continuous-wave interference, atmospheric reflections or simply AI over-sensitivity, when a neural network “sees” patterns in random noise.

Multiply that across hundreds of sensors worldwide, across edge case events — the rare, extreme scenarios that are most likely to confuse the model —- and across over-sensitivity, a side effect of trying to detect the undetectable — and the clutter becomes digital as well as physical.

This is where the PNN could make a difference. By connecting radar, optical and infrared sensors across the globe, it provides a built-in mechanism for cross-verification. If one radar station reports a new object, but no other optical or orbital node confirms it, the network can flag the detection as suspicious. Conversely, if multiple sensors independently detect the same signature, confidence rises exponentially. This multi-sensor consensus is one of the most powerful weapons against false positives. Instead of relying on one pair of “eyes,” the PNN would allow the entire planet to look, compare and agree.

Another defense lies in the temporal intelligence of the system. LSTM-based models, as pointed out above, analyze not just individual frames but the evolution of signals over time. A real orbital object follows predictable physics, its motion across the sky is continuous and coherent. A false positive, in contrast, appears suddenly and disappears just as fast. By tracking temporal consistency, LSTMs can learn to reject transient anomalies by effectively asking: “Is this object behaving like something in orbit, or like a glitch?” This temporal reasoning turns raw detections into stable tracks, filtering out the fleeting noise that haunts single-sensor systems.

To further refine decisions, each detection in the PNN can be assigned a confidence score, a number expressing how likely it is to represent a real object. This score integrates multiple factors: signal-to-noise ratio, multi-sensor correlation, trajectory stability and agreement among different AI models.

When multiple models say, a CNN, an autoencoder and a transformer evaluate the same data, their results can be combined through ensemble learning. If all models agree, the detection is likely real. If only one does, it’s probably noise. This kind of AI committee dramatically reduces false positives, replacing single-model overconfidence with collective judgment. Despite automation, human expertise remains critical: Operators can review ambiguous detections through visualization dashboards that show signal strength, orbital geometry, and sensor correlations.

Each confirmed false positive helps retrain the model, improving its future resilience, resulting in a feedback loop between machine learning and human reasoning. It’s a pragmatic middle ground, and one that’s quickly proving its value in a rapidly evolving space domain.

AI and the future of space security

The trajectory of AI in space security points only in one direction: towards increasingly sophisticated systems capable of both detecting and actively preventing space-based threats.

As machine learning models become more advanced and edge computing and TPU capabilities expand, we’re approaching a future where AI could autonomously predict potential collisions, predict, detect and classify signal interference in real-time and automatically implement countermeasures against identified threats.

In the future, we’ll see even more applications, some of which we cannot yet imagine from coordinating multiple satellites for distributed threat detection to quantum-resistant security protocols, and advanced predictive maintenance capabilities. All of which will extend satellite operational lifespans and maintain safety and security integrity.

In other words, AI in space applications, be they ground or space based, are an absolute game changer for the future of space safety and security, and we cannot wait to see what’s on the horizon.

Hans Martin Steiner is vice president and head of business segment for the Institutional Space Business at Terma

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly