Now Reading: What Germany got right (and wrong) in its first ever space strategy

-

01

What Germany got right (and wrong) in its first ever space strategy

What Germany got right (and wrong) in its first ever space strategy

Germany’s first national space security strategy was unveiled last month to much fanfare. And who’s surprised? It was long overdue, and puts into plain language a simple but vital truth: space is now a theatre of power. With Russia and China long having treated orbit as contested territory, and the United States preparing daily for a potential conflict in space, Europe must get moving — and Germany seems willing to lead the way. The strategy sets a direction of travel, and that isn’t to be dismissed. But its success will depend on whether policy keeps pace with technology, whether industry is empowered to move with the speed that space demands and whether old habits are cast off, or die hard.

First, let’s consider what the strategy gets right. It recognizes that resilience is now the number-one design principle for satellites. Civilian and military operators alike need spacecraft that can withstand the brutal conditions of space and the unwanted interference of hostile actors. That means resistance to radiation, to heat, to electromagnetic pulses and to targeted disruption. Tougher, longer-lasting satellites guarantee dependable Earth observation, navigation and communications in an increasingly fraught orbital environment.

The strategy’s authors also underscore the need for credible deterrence. This is not necessarily about offensive capabilities. It’s more about making it clear to an adversary or potential adversary that its actions will not have the desired effect. In practice, that means decoys, stealth materials, thermal-management layers and electromagnetic shielding. These are already available, enabled by Europe’s fast-growing advanced materials sector, which I can say with confidence — given that my company develops conductive, ultra-resilient fibres — already has a large presence in Germany.

Also emphasized in the strategy is European industrial sovereignty and cooperation. This is wise: space begins on Earth. Shared standards, shared supply chains, shared R&D pipelines — these are needed across the EU and across NATO. Encouraging dual-use development, too, is welcome. Many of the forms of technology that make satellites more resilient will also cut costs and improve civilian services. To grow, Europe’s space sector must serve both markets.

So what’s missing? For one thing, brutal honesty about the obstacles in our way. The key challenge isn’t funding: Berlin plans to spend 35 billion euros ($41.1 billion) on military space capabilities between now and 2030. The challenge is speed. Today, there is a chronic lack of communication between the military and industry; in Germany, men and women in the armed forces are discouraged from speaking openly with companies, including firms working in defense. The aim is to avoid creating unfair advantages, but the effect is that the broader industry has little insight into concrete, operational needs. A policy of silence does not lead to fairness. In fact it does the opposite. It benefits the primes and their lobbyists, who thanks to their historic relationships get the insights they need while the newer and smaller players don’t. This is a problem, in my view. Other European countries come upon sensible compromises, balancing constructive dialogue with military integrity. Germany needs to do something similar. Open dialogue with vetted individuals should be possible.

Another obstacle is regulation. Many advanced materials and space components count as dual-use, even when sold to domestic customers. Export controls, especially through the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control, can delay shipments for months. For the bigger primes, this is an inconvenience; but for start-ups and scale-ups, it can bring innovation to a juddering halt. Rapid prototyping is impossible when every iteration requires more paperwork. The result is that genuinely cutting-edge ideas do not turn into the defense technology of tomorrow. Worse, ongoing ambiguity about what “dual-use” really means creates uncertainty for investors and founders. If you can’t predict whether your work will fall under a restrictive regime, you might avoid developing certain forms of high-end technology. Europe is in the strange position of encouraging innovation verbally while preventing it through regulation and vagueness. Again, this counts doubly for the smaller firms, which don’t have bottomless funds or teams focused solely on compliance.

Because of these structural issues, Germany’s ambition is running ahead of its processes. Space security, as I’ve already said, depends on speed: speed of interaction, integration, feedback. Without reform, Germany risks spending billions yet still needing to import its most essential forms of technology from unreliable partners and potential adversaries,

Are there solutions? One would be to create a European Defense Industrial Board that brings together Germany, France, the UK, Italy and others, and that includes industry representatives. It should also include academics, representatives from startups and primes, military players and politicians. The remit would be narrow and clearly defined: align investment, coordinate regulation, accelerate approvals and ensure that innovation flows across borders. Europe does not need another forum for endless discussion. It needs a mechanism for decisions. This could just as easily work at the national level, as Stanford University’s Niall Ferguson has argued.

But I repeat: Germany has taken a positive step by publishing a strategy. Its task now is to make sure that it becomes more than a mere aspiration, because a strategy shorn of the conditions it needs to become a reality is just wishful thinking. If Berlin wants a sovereign, resilient, European presence in orbit, it has to treat defense companies as partners, not risks. It must treat speed as a requirement, not a luxury. And it needs to update those rules that were written for a different, more peaceful era.

Space security will define geopolitical stability for decades. Europe can’t afford to fall behind. Germany has acknowledged this. Now, policy must follow so that European entrepreneurs can act.

Robert Brüll is the CEO of FibreCoat.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion (at) spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. If you have something to submit, read some of our recent opinion articles and our submission guidelines to get a sense of what we’re looking for. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent their employers or professional affiliations.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

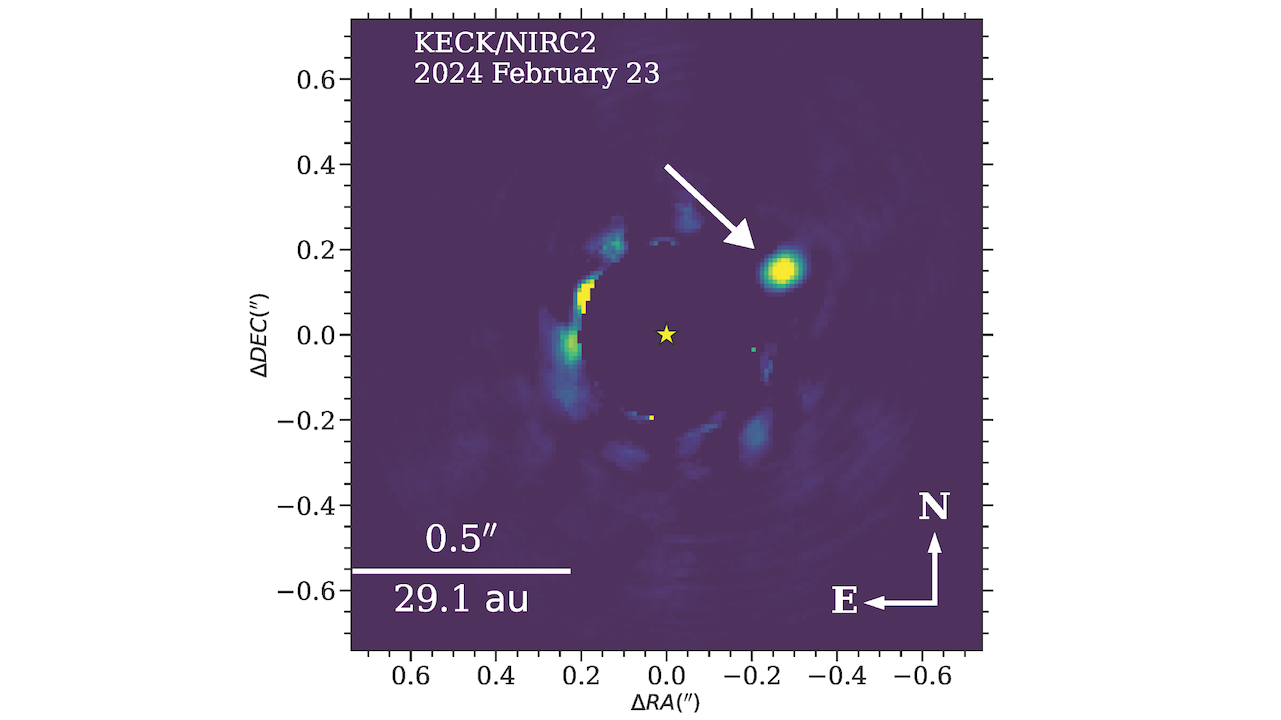

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

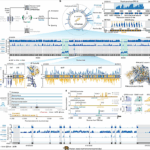

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly