Now Reading: Why do some places on Earth get far more solar eclipses than others?

-

01

Why do some places on Earth get far more solar eclipses than others?

Why do some places on Earth get far more solar eclipses than others?

On Aug. 2, 1153, Jerusalem — one of the oldest cities in the world — experienced a total solar eclipse for the last time until Aug. 6, 2241, according to the book Totality by the late Fred Espenak, NASA’s eclipse calculator extraordinaire. That’s a gap of 1,108 years. Meanwhile, people living in a quadrant covering about 32,400 square miles (52,200 square kilometers) in Illinois, Missouri, and Kentucky experienced totality twice in just 6 years, 7 months, and 18 days.

Why are generation after generation of people in Jerusalem so unlucky, while those in Perryville, Cape Girardeau, Paducah, Carbondale, Makanda, Harrisburg and Metropolis are overfamiliar with totality from their backyards? Why do some locations on Earth never see a total solar eclipse within multiple human lifetimes, while others have a path of totality — typically about 100 miles wide — cross their home regularly?

How often do total solar eclipses occur?

The frequency of total solar eclipses is difficult to pin down because the intervals between them occurring at any one place are highly irregular. The reference work is a 1982 paper by Belgian astronomer Jean Meeus, a legend of mathematical astronomy. Using an HP-85 personal computer — one of the first available — Meeus calculated paths of totality over the next 600 years to arrive at an answer. The received wisdom was that a total solar eclipse occurs at a given place on Earth once every 360 years, on average, but that figure traced back to a 1926 astronomy textbook that offered no supporting calculation. Meeus’ calculations refined the figure to an average of 375 years. This number has been the standard ever since, but given advances in computing, recent efforts have sought to refine it by crunching more data in different ways.

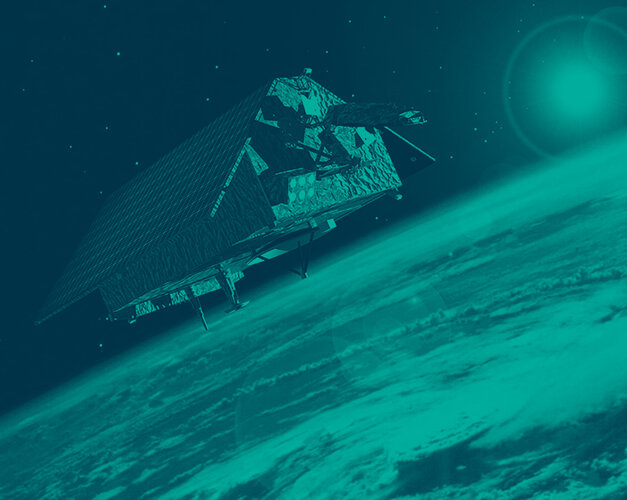

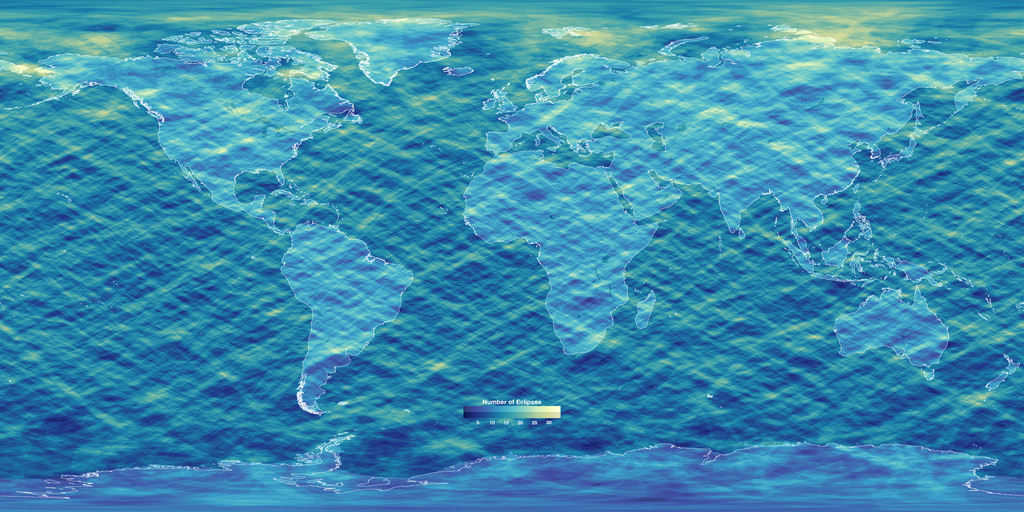

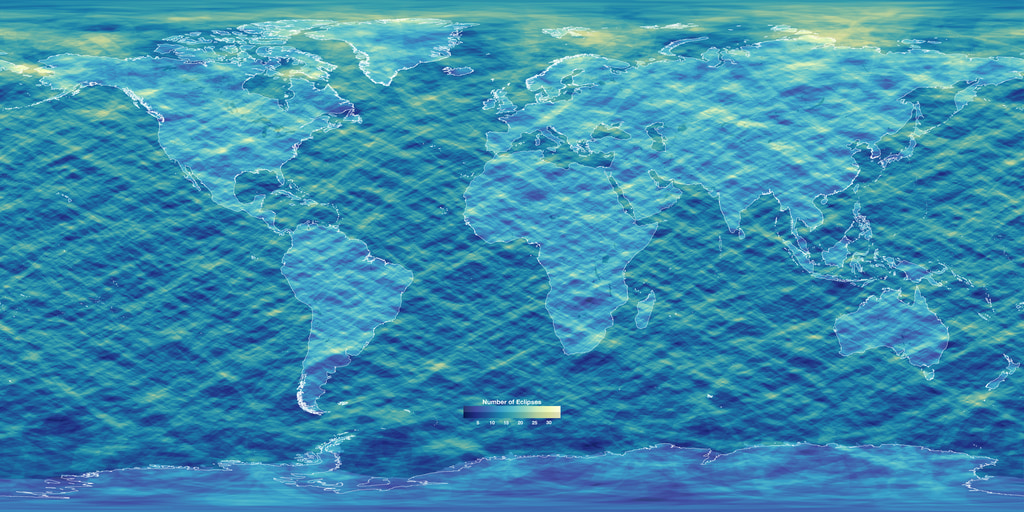

NASA’s 5,000-year heat map

In March 2024, just before the second “Great American Eclipse” in seven years, Ernie Wright at NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio published a heat map of paths of totality across Earth. It contains the paths of 3,742 total solar eclipses across the 5,000 years between 2,000 B.C. and 3,000 C.E. It was created using the Five Millennium Canon of Solar Eclipses, a list of eclipses calculated by Jean Meeus and the late Fred Espenak, published in 2006. “It’s evident from the heatmap that a total solar eclipse can happen absolutely anywhere on Earth,” wrote Wright. “In fact, there isn’t a single pixel in the map that isn’t visited by at least one eclipse — not a single goose egg in any of the 14.6 million points sampled by the map.” Every pixel on Wright’s map experiences between one and 35 total solar eclipses in the 5,000-year period.

Time and Date’s 14,999-year study

A paper submitted to arXiv in February and accepted for publication in the Journal of the British Astronomical Association later this year — is the most comprehensive attempt, covering 35,538 solar eclipses across 14,999 years, a computing job that used 662,000 gigabyte-hours of memory and 147,000 core hours over 102 days of continuous calculations. It found that a new, refined figure — 373 years. “Meeus’ number is so widely quoted, and we thought it would be interesting to see what would happen if you let a modern computer loose on the same problem,” lead author Graham Jones, an astrophysicist and science communicator at Time and Date, told Space.com. However, as well as refining Meeus’s work, this research uncovered deeper patterns in where and when total solar eclipses occur, tied to Earth’s orbital mechanics.

The ‘latitude effect’

Both recent papers reveal patterns of where and when total solar eclipses occur that were previously only suspected. A striking finding from Time and Date’s paper is a “latitude effect,” whereby the frequency of solar eclipses of any type peaks around the Arctic and Antarctic Circles and is lowest near the equator. The reason is simple — near the polar circles, the sun‘s path skims along the horizon during certain times of the year, increasing the window during which an eclipse can occur.

Wright’s research for NASA found that more total eclipses happen in the northern hemisphere than in the southern hemisphere, mostly because of Earth’s slightly elliptical orbit around the sun. They’re also more frequent in summer because the sun is up longer then. “Summer in the northern hemisphere happens when the Earth is near aphelion, its farthest distance from the sun for the year, and this makes the sun a bit smaller in the sky, giving the moon a better chance of covering it completely,” writes Wright. However, the dates of aphelion and perihelion (when Earth is its closest to the sun for the year) drift over the centuries. “There’s a 21,000‑year cycle where the dates of aphelion and perihelion drift through the calendar, so about 4,500 years from now, aphelion and perihelion coincide with the equinoxes, and at that stage, neither hemisphere has this advantage in terms of getting the sun closer or further away during the summer months.” In about 9,500 years, this alignment will reverse, shifting the advantage to the Southern Hemisphere. It’s this 21,000-year cycle that explains why the actual interval between total solar eclipses in any one place remains highly irregular when compared to the average.

What about ‘ring of fire’ annular solar eclipses?

The frequency of annular solar eclipses — when a new moon that’s farthest from Earth blocks only the center of the sun’s disk to cause an annulus (ring) eclipse — was also covered by Meeus and Time and Date. The research reveals that an annular solar eclipse occurs at a given place on Earth once every 224 years (Meeus) or 226 years, on average, respectively. Why are they more frequent than total solar eclipses? “There are more annular eclipses because if you just take the average size of the sun and the moon across all the eclipses, then generally the sun is more often just a bit bigger than the moon,” says Jones.

That’s a trend that’s only going to increase. Total solar eclipses occur because the moon and the sun can have the same apparent size in Earth’s sky — the sun is about 400 times wider than the moon, but the moon is about 400 times closer. However, the moon is slowly moving away from Earth by 1.5 inches (3.8 centimeters) per year, which has devastating consequences for eclipse chasers. “If you look at really long time scales, as the moon slowly moves away, total eclipses eventually come to a halt altogether.” The good news? That won’t happen for about 600 million years.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

07True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

07True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer